Unusual choreography of the Egyptian coup

The Egyptian transition has been messy and instructive

For all the more-in-sorrow-than-in-anger protestations, this coup d’Etat was about as retro as they come.

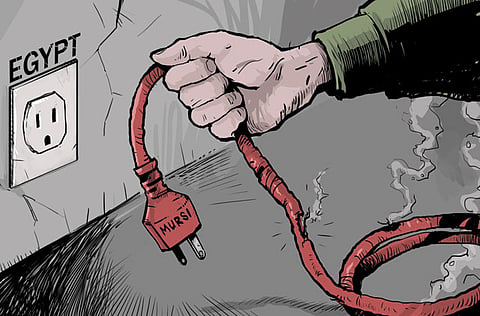

Troops surrounded state broadcasting headquarters early on and, once the army commander had finished his televised announcement of the government’s demise, the plugs were pulled on the ruling party, silencing its television stations.

However, the choreography of this coup — ousting Mohammad Mursi, Egypt’s first democratically elected and only Islamist president — was unusual.

General Abdul Fattah Al Sisi, the Army Chief-of-Staff, mobilised extra divisions of no mean significance. As he replaced Mursi and his Muslim Brotherhood with a transitional government, he was flanked by the Shaikh of Al Azhar university, the leading Sunni Muslim authority; the Pope of Egypt’s sizeable Coptic minority; Mohammad Al Baradei, Nobel peace laureate and leader of Egypt’s liberals; and youthful activists who had brought down the army-backed dictatorship of Hosni Mubarak in 2011 — the high spring of the new Arab awakening.

As the vast crowds in Tahrir Square erupted in joy, every bit as spectacular as the way they greeted the toppling of Mubarak, it is fair to ask who mobilised whom.

Al Baradei, speaking after General Al Sisi, greeted the coup as a reset for the Egyptian revolution and the Arab Spring. Yet, it is obviously an unhappy state of affairs when those who profess to be liberals need army bayonets to press their case.

When Bashar Al Assad took power in Syria in 1970 as a “corrective movement”, after revolving-door coups and mayhem, or indeed when the legendary “Free Officers” of Jamal Abdul Nasser toppled the louche Egyptian monarchy in 1952, they were also greeted as saviours. The rest of the story Syrians and Egyptians know all too well.

The Islamists did not hijack the Egyptian revolution, they were just far better organised than their liberal and leftist rivals in scooping up votes in the five electoral exercises that followed the fall of the Mubarak regime. The reasons have long been obvious.

The Al Assads and the Mubaraks, the Muammar Gaddafis and the Saddam Hussains, all of them at different points bolstered by the West, laid waste to the entire spectrum of organised politics in their countries — with the exception of the mosque, around which Islamist dissidence regrouped. Of course, secular politicians are at a disadvantage, but polls show they have a big constituency. Under dictatorship, they took it for granted. In a democracy they have to organise it.

The Egyptian transition has been messy and instructive — and not just for Egypt. The spectacular failure of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt — the country of its birth 85 years ago, the most populous Arab country, which still presumes to regional influence — heralds a setback for mainstream political Islam across the broader Middle East.

Arab despotism was good at manufacturing Islamists. However, that did not mean the Islamists would be any good at governing. Mursi, for example, while democratically elected, failed to behave like a democrat. His abortive constitutional coup last autumn, attempting to place his government above the judiciary, and his intolerance of criticism and attempts to pack Egypt’s institutions with his followers, alienated all but hard core Islamists. Unable to meet the needs of ordinary Egyptians for jobs and security, electricity and services, he was accountable to the Brotherhood but not citizens of the republic.

Even foreign governments and international institutions were dealing with Khairat Al Shater, the deputy supreme guide of the Brotherhood, which, in its paranoid secretiveness, ran a parallel government.

Is the fall of Mursi a setback for democracy? Of course it is, but it cannot be taken in isolation.

The spectacle presented by the first elected parliament after the fall of Mubarak — an Islamist-dominated assembly arguing about prayer times and obsessing over curtailing women’s rights — was a setback for democracy. Attempts to manipulate the judiciary by all sides — the generals, the Mubarak “deep state”, the liberals and the Brotherhood — were a setback for democracy.

By no means least, the manifest inability of secular, urban and modern Egyptians to organise their political representation was — and remains — a setback for democracy.

— Financial Times