Time for a reality check

Zardari’s visit to Punjab has political symbolism written all over it

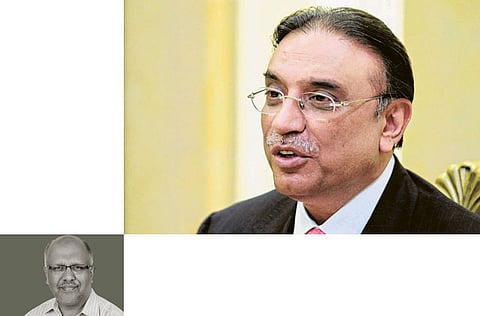

When Pakistan’s President Asif Ali Zardari ventured out in the past week to personally visit two localities across the populous Punjab province, his journey was immediately surrounded by unanswered questions. Since his unexpected political rise to becoming Pakistan’s head of state in 2008, following the assassination of his wife, Benazir Bhutto, Zardari has adopted an unusual bunkered mentality.

While Pakistan remains surrounded by an acute security crisis, Zardari has remained practically confined to his well-fortified presidential residence — effectively a bunker.

Rather than reach out to the front lines, even symbolically, the Pakistani president has preferred to remain an observer from the rear.

Speaking of symbolism, the president has chosen to largely avoid appearances even in places like a monument outside the Pakistan Army’s general headquarters in Rawalpindi, created in memory of the brave soldiers and officers who fell as martyrs while deployed on the front lines. Avoiding the journey to that monument, which is roughly half-an-hour’s driving distance in a VVIP motorcade from the presidential residence, largely underlines Zardari’s well-documented style.

However, now, his foray into Punjab is not without relevance to Pakistan’s emerging politics. By March 2013, the country’s parliament will have to be dissolved, leading the way to the next elections within 90 days thereafter. Ahead of that historic moment, politicians close to Zardari and his ruling Pakistan People’s Party (PPP) have begun predicting a comeback for the ruling structure.

Yet, in pressing that contention, there are indeed two important missing elements.

On the one hand, Pakistanis across the country’s mainstream have suffered much during Zardari’s watch. In the past four years, new investments have virtually dried up while the PPP-led ruling structure has simply failed to tackle some of the toughest challenges facing the country. During this time, an already difficult energy crisis has become acute while little headway has been made in undertaking long overdues and difficult reforms. In brief, the government has little to show for success stories that will carry meaning for ordinary Pakistanis.

On the other hand, some of the key issues surrounding Zardari cannot be detached from Pakistan’s overall political trends. As a country which has been ruled by the army for half of its life as an independent state, there is indeed a case for the consolidation of a young democracy.

Yet, Zardari’s own battles, notably one to resist calls for reopening of investigations of corruption against him in Switzerland, have hardly helped to either reinforce the image of a credible presidency or indeed a credible president. Consequently, Zardari’s own image or that of a government led by his party, has hardly become a source of pride for ordinary Pakistanis.

In this background, President Zardari’s emergence from his bunker only reinforces his determination to begin reclaiming ground that has been lost by the PPP. On his latest stopover in the central city of Multan, Zardari was warmly received by Yousuf Raza Gilani, the former prime minister, forced out under a Supreme Court order earlier this year when he refused to formally request the Swiss authorities to reopen the corruption related investigations in Switzerland.

It was a stopover that has political symbolism written all over. The hope for Zardari is probably that of bolstering Gilani’s credentials to begin rebuilding the PPP in Multan and its surrounding areas. Yet, in contrast to the officially provided glamour surrounding such visits, the reality of Pakistan’s grass roots not too far from Zardari also remains stark.

Just two to three hours of driving distance from Multan begins another eye-opening reality check in the dismal conditions surrounding ordinary Pakistanis. Following this years’ floods caused by monsoon rains, almost a million Pakistanis from poverty-stricken homes were forced to lives of squalor. Today, an overwhelmingly large majority of those unfortunate Pakistanis remain in continued distress, waiting for official aid.

Notwithstanding Zardari’s journey, it is the failure of the Pakistani government to tackle such real-life crises which will eventually decide the ruling structure’s political fate. Beyond such crisis-stricken localities, there are many additional challenges faced by Pakistanis in their daily lives which will indeed decide the fate of contenders for political office when parliamentary elections are out of the way next year.

For Zardari too, the moment of reckoning with his tainted ruling structure may have finally arrived. His emergence from his well-fortified and bunkered presidency may already be too late in the day.

Farhan Bokhari is a Pakistan-based commentator who writes on political and economic matters.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox