The politics of erasing history

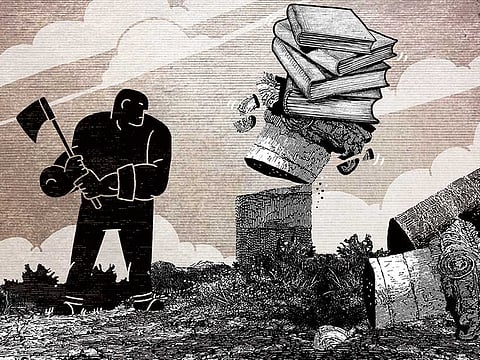

A casualty of today’s violence is the past as cultural artefacts are destroyed in what can be described as ‘historicide’

In a world of disarray, the Middle East stands apart. The post-first World War order is unravelling in much of the region. The people of Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and Libya have paid an enormous price.

But it is not just the present and future of the region that has been affected. An additional casualty of today’s violence is the past. Daesh (the self-proclaimed Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant) has made a point of destroying things it deems insufficiently Islamic.

The most dramatic example was the magnificent Temple of Baal in Palmyra, Syria. As I write this, the city of Mosul in northern Iraq is being liberated, after more than two years of Daesh control. It will not come soon enough to save the many sculptures already destroyed, libraries burnt, or tombs pillaged.

To be sure, destruction of cultural artefacts is not limited to the Middle East. In 2001, the world watched in horror as the Taliban blew up the large statues of Buddha in Bamiyan. More recently, radical Islamists destroyed tombs and manuscripts in Timbuktu. But Daesh is carrying out destruction on an unprecedented scale.

Taking aim at the past is not new. Alexander the Great destroyed much of what is now called Persepolis more than 2,000 years ago. The religious wars that ravaged Europe over the centuries took their toll on churches, icons, and paintings.

Stalin, Hitler, and Mao did their best to destroy buildings and works of art associated with cultures and ideas viewed as dangerous. A half-century ago the Khmer Rouge destroyed temples and monuments across Cambodia.

In fact, what might best be described as “historicide” is as understandable as it is perverse. Leaders wishing to mould a society around a new and different set of ideas, loyalties, and forms of behaviour first need to destroy adults’ existing identities and prevent the transmission of these identities to children.

Destroying the symbols and expressions of these identities and the ideas they embody, the revolutionaries believe, is a prerequisite to building a new society, culture, and/or polity.

For this reason, preserving and protecting the past is essential for those who want to ensure that today’s dangerous zealots do not succeed. Museums and libraries are invaluable not only because they house and display objects of beauty, but also because they protect the heritage, values, ideas, and narratives that make us who we are and help us transmit that knowledge to those who come after us.

Banning traffic in stolen art

The principal response of governments to historicide has been to ban traffic in stolen art and artefacts. This is desirable for many reasons, including the fact that those who destroy cultural sites, and enslave and kill innocent men, women, and children, acquire the resources they need in part from the sale of looted treasures.

The 1954 Hague Convention calls on states not to target cultural sites and to refrain from using them for military purposes, such as establishing combat positions, housing soldiers, or storing weapons. The goal is straightforward: to protect and preserve the past.

Alas, one should not exaggerate the significance of such international agreements. They apply only to governments that have chosen to be a party to them. There is no penalty for ignoring the 1954 Convention, as both Iraq and Syria have done, or for withdrawing from it, and it does not cover non-state actors (such as Daesh). Moreover, there is no mechanism for action in the event that a party to the Convention or anyone else acts in ways that the Convention seeks to prevent.

The hard and sad truth is that there is much less in the way of international community than the frequent invocation of the term suggests.

Indeed, a world that is unwilling to fulfil its responsibility to protect people, as has been shown most recently in Syria, is unlikely to come together on behalf of statues, manuscripts, and paintings.

There is no substitute for stopping those who would destroy cultural property before they do it.

In the case of today’s principal threats to the past, this means discouraging young people from choosing radical paths, slowing the flow of recruits and resources to extremist groups, persuading governments to assign police and military units to protect valued sites, and, when possible, attacking terrorists before they strike.

If a government is the source of the threat to cultural sites, sanctions may be a more appropriate tool.

Indicting, prosecuting, convicting, and jailing those who carry out such destruction might prove to be a deterrent to others — similar to what is required to stop violence against persons.

Until then, historicide will remain both a threat and, as we have seen, a reality. The past will be in jeopardy. In that sense, it is no different from the present and the future.

— Project Syndicate, 2017

Richard N. Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, is the author of A World in Disarray: American Foreign Policy and the Crisis of the Old Order.