The only solution is a non-sectarian Iraq

Real challenge is to persuade Sunnis that they can be truly equal citizens

The revival of civil war in Iraq is not about ancient sectarian hatreds — that is what the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Isil) wants you to think. It is a hardcore ideological group exploiting the political disaffection of one community to stoke sectarian war. Iraq’s broken political system and the failure of its political elite to prioritise reconciliation over personal gain has led to a collapse of faith in the political system, leaving Iraq vulnerable to this sectarian propaganda. However, if the Iraqi government buys the Isil narrative and treats Sunnis as implacable opponents of Shiites, Isil will have succeeded in stoking the civil war it has so desired.

Ever since the formation of Iraq as a nation-state by European powers, it has been easy to dismiss it as an artificial country that was bound to fail. A Sunni elite was installed to govern over a majority Shiite population and a restive Kurdish community that had fought and lost the battle for independence. But throughout Iraqi history, the importance of identity has waxed and waned according to changing political realities.

At times, when Iraq’s political battle lines divided communists from nationalists, and nationalists from Baathists, identity seemed incidental and even passe. Many Iraqis grew up in households where it was rude to refer to people’s sectarian identity and where intermarriage created large families of mixed religious practice.

However, at other times, when the presence of distinct ethnic and religious groups was seen as posing a threat to the political establishment, identity became more important. During the Iran-Iraq war, the Baathist government feared that Iraqi Shiites would sympathise with their co-religionists in Iran and unleashed waves of repression against them.

When coalition forces stormed Iraq in 2003, they found a society devastated by war, deprivation and brutal Baathist rule. The war itself deeply divided Iraqi society, pitting those who saw it as Iraq’s salvation against others who decried it as a neocolonial invasion.

The Shiite and Kurdish communities, who had suffered most at the hands of the Baathist regime, tended to celebrate their entry into power, while the Sunnis, who had dominated Iraq’s power structures for generations, overwhelmingly rejected the new Iraq. Sunnis, and some Shiites, fought against the presence of coalition troops. However, this violence was quickly exploited by Al Qaida affiliates, some foreign and some Iraqi, who gained a foothold in despondent Sunni heartlands.

These hardcore ideologues began to target Shiites in bomb attacks with the explicit desire to stoke civil war. They believed that a civil war in Iraq would force Sunni countries around the world to defend Sunnism and somehow lead to the revival of the Islamic caliphate. These aims were antithetical to the beliefs of the vast majority of the Sunni population, but as more and more Shiites were violently killed by Islamist militants, they began to fight back indiscriminately. The cycle of revenge led to a horrific civil war in which countless innocent Iraqis were slaughtered.

But that civil war has ended. Iraqi Sunnis realised that Al Qaida in Iraq was an abominable entity that, by stoking civil conflict, was threatening to bring about the extermination of Iraq’s minority Sunni community. Together with the support of coalition forces, local Iraqi Sunni leaders fought against Al Qaida and won, driving them out of the country or into hiding. Iraqi Sunnis began to vote and to field candidates in the parliamentary elections. Iraqi politicians started to brand themselves as cross-sectarian nationalists who wanted to build a unified Iraq.

The parliamentary elections in 2010 represented the apex of hope for a new future in which Iraqis would live and prosper together. Prime Minister Nouri Al Maliki’s Shiite-dominated State of Law coalition went head-to-head against former prime minister Ayad Allawi’s Sunni-dominated Iraqiya coalition. As Iraqiya won, the Sunnis were ecstatic. It had seemed impossible that a largely Sunni coalition could win at the ballot box and the prospect of a new government that reflected the priorities of Iraq’s Sunni community was mesmerising.

It was not to be. Al Maliki outmanoeuvred the winning coalition and managed to stay Prime Minister.

Isil is not the army of Iraq’s Sunnis, it is an extraordinarily dangerous entity that is exploiting the alienation of Iraq’s Sunni community to provoke a second civil war. Retracing the terrible path trodden by Al Qaida in 2005 and 2006, Isil is again inflicting mass-casualty attacks on Shiite civilians and threatening Shiite shrines. Now, thousands of young Shiite men are joining Shiite militias and, unless dramatic action is taken by the Iraqi government, it is only a matter of time before unfettered sectarian bloodletting begins.

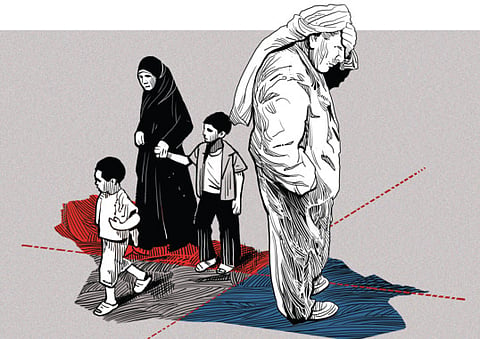

Although it is extraordinarily difficult at a time when Iraqis are under attack, the Iraqi government needs to resist the sectarian Isil narrative and to recognise that Isil is distinct from Iraq’s Sunni community. Iraqi Sunnis do not want to be governed by Isil, they do not support the massacre of Shiite civilians and they do not want another civil war. But they also do not believe there is a place for them in Al Maliki’s Iraq. Iraq’s politicians must persuade them that a future does exist in which Sunnis can participate as equal citizens in an Iraqi state and that this is something worth fighting for.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Dr Nussaibah Younis is International Security Programme research fellow at Belfer Centre for Science and International Affairs, Harvard Kennedy School.