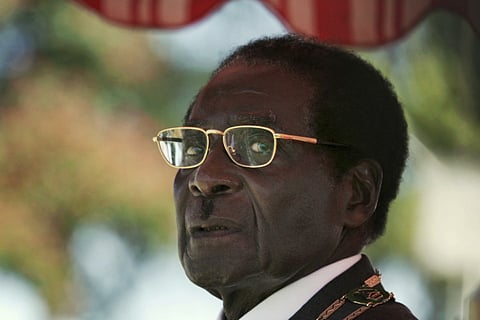

The fall of Robert Mugabe sends an ominous signal to Africa’s dictators

The fall of the Zimbabwe president has shown us once again that autocrats and strongmen always appear invulnerable — until the day they aren’t

The dictator Robert Mugabe has fallen. After days of uncertainty following an ambiguous coup, he finally bowed to pressure from his former allies and ordinary Zimbabweans.

In his resignation letter, Mugabe tried to depict his decision to step down as voluntary, a generous gesture to allow for a smooth transfer of power. The announcement halted impeachment proceedings that had already been launched against him by parliament. It’s a huge moment for Zimbabweans who have yearned for change. It’s also significant news to Africans who are hungry for democracy. Young people in Zimbabwe have never known any other leader apart from Mugabe. His wife Grace once said that her husband’s spirit would rule Zimbabweans, hinting that the old man would govern forever. But his end has arrived after 37 years in power.

It’s a warning shot for many African leaders who are clinging to power while oppressing their people.

It is an ill omen for Africa’s longest-serving leader, Cameroon’s Paul Biya (seven years as prime minister and 35 years as President). Mugabe’s fall is also certain to send an unsettling message to Equatorial Guinea’s President Teodoro Obiang Nguema (38 years), General Denis Sassou-Nguesso of Congo Republic (a total of 33 years), Uganda’s Yoweri Museveni (31 years) and Rwanda’s Paul Kagame (23 years). The list is long.

Power hungry

These strongmen all have the same approach to governance. Their ruling parties control the army and the police, key businesses and financial institutions, and the state-run media. The parties decide who lives or dies. Zimbabwe’s ruling Zimbabwe African National Union — Patriotic Front (Zanu-PF) is the model.

Mugabe has commanded a support base within the ruling party for decades. Many Africans once regarded him as a hero for bringing independence to Zimbabweans and ending white-minority rule — and some probably will continue to do so. But to his critics, he is the epitome of the power-hungry African dictator, a man who destroyed an entire country just to keep his job.

In June 2015, just a month after fleeing my home country of Rwanda, I met a Zimbabwean journalist at a Global Media Conference in Germany. He was lamenting how freedom of speech and freedom of the press were shrinking under Mugabe. Because it was my first month of exile, my heart was too heavy to sympathise with him. I told him that Zimbabweans were lucky, because Mugabe would have to leave power soon anyway because of his age. Even so, he managed to hang on longer than I expected.

In Rwanda, by contrast, there is a strongman who still has the energy to control everything, including the military, the police and the citizenry. President Kagame, 60, is the youngest leader on Africa’s top-10 list of long-serving heads of state. (That’s not counting Mswati III of Swaziland, who has been king for 31 years and is 49 years old.) If he maintains his hold on power and lives as long as Mugabe has, Kagame will end up serving for 53 years.

But I’m not sure he’ll be able to pull it off. Mugabe’s fall shows us once again that dictators always appear invulnerable — until the day they aren’t.

‘The crocodile’

Perhaps because of his age, Mugabe forgot some key pages from the dictators’ rule book. He forgot to choose a successor of his choice; now his former allies are picking one against his will. His former deputy, Emmerson Mnangagwa (nicknamed “the Crocodile”), whom he fired, took over from him.

If you’re a dictator, your ideal successor should be a blood relation (see Bashar Al Assad, the President of Syria) or your wife. Blood is thicker than water, and you may not trust a relative, but you’ll always know where they live. If that isn’t a possibility, then you must choose someone whose general skills are inferior to yours.

The point: If you want to be remembered as a great leader, make sure your successor is an idiot. Mugabe missed this opportunity.

The lesson here is plain and simple: Don’t wait until your people are enraged. If things are looking bad for you during your time in power, leave early and cover your tracks well. However you choose to do it, make sure your departure is dramatic or mysterious. Then your place in history is assured.

It’s now up to Mugabe’s old class colleagues to revisit their exit strategy before they end up following their mentor into retirement.

— Washington Post

Fred Muvunyi, a former chairman of the Rwanda Media Commission, is an editor at Deutsche Welle, Germany’s international broadcaster.

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox