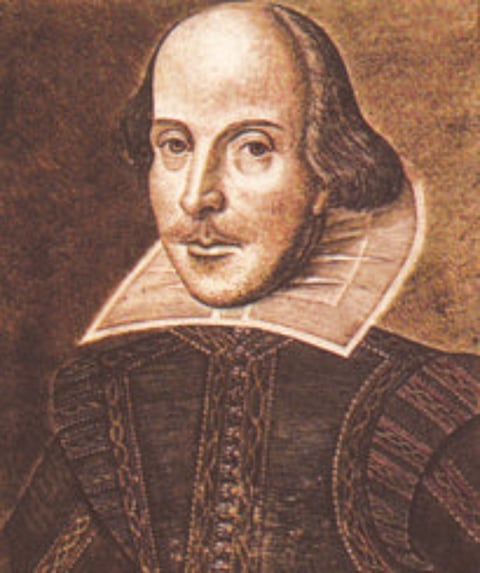

Shakespeare, the reactionary bard

The man’s plays are suffused with contempt for that lower species of men, who are portrayed as greedy and grasping, and common people, who appear as nameless, faceless props

As a commentator true to his craft, I’ll tell you that William Shakespeare was a retrograde — a racist, a reactionary and an imperialist who mirrored the pompous ethos of the Elizabethan Age that he was a product of, an ethos that he transmitted to later generations of Englishmen and Englishwomen who absorbed it almost by osmosis.

This year marks the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death and the English-speaking world, notorious for its ethnocentric smugness, will go on a binge of commemorative extravaganzas of plays, spin-offs, readings, operas and books, including (hold on to your hat!) one called Shakespeare in Swahili, that purportedly looks at the “impact” of the Bard’s work on people in Eastern and Central Africa. A New Orleans Jazz funeral will mark the Bard’s death and the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington will sponsor a 50-state tour of the First Folio.

The homage paid to Shakespeare, of course, precedes our time. It comes from Ben Jonson, whose enduring eulogy (which appeared in the preface to the First Folio) tells us that “He was not for an age, but for all time”; from John Dryden, who spoke of his “comprehensive soul”; and from John Milton, who spurned the idea of setting the Elizabethan playwright’s talent beside that of Sophocles. But that homage is also paid in our own time and comes from the likes of George Steiner who averred — in a paper he wrote in 1964 to mark the 400th anniversary of the Bard’s birth — that “To say that Shakespeare is not only the greatest writer who has ever lived, but who will ever live, is a perfectly rational statement”.

Will someone tell me what this brouhaha is all about? The man’s plays, after all, are suffused with contempt for that lower species of men, who are portrayed as greedy and grasping, and common people, who appear as nameless, faceless props. English-speaking folks, including Britain’s Prime Minister, David Cameron, who published a piece in The Views section of Gulf News last Tuesday, have written rhapsodically of the Bard’s “universal” appeal; how he enchants people in countries all over the world; and his talent for dramatising the timeless truths of the human condition. You find him relevant, we are told, at every moment and place of immediacy in our lives, whether one lives in the Indian Subcontinent or the Alaskan wilderness. And any suggestion that one may question that notion will only invite derision. Shakespeare is the transcendent Bard, is he not?

Not so transcendent, relevant or universal, however, if you are — though English-speaking — an Irish revisionist and contrarian critic.

Consider, as a case in point, Emer O’Toole, a professor of Irish Studies at Concordia University in Canada, who begs to differ. Her article, ‘Shakespeare universal? No, it’s cultural imperialism’, caused a stir when it first appeared in May, 2012, in the Guardian. In it she argued that “Shakespeare is full of classicism, sexism, racism and defunct social mores”. Hang on, there’s more. “The Taming of the Shrew ... is about as universally relevant as the chastity belt, while The Merchant of Venice ... is about as universal as the Nuremberg Laws”. And here’s the clincher from the angry Irishwoman: “So where has the idea that Shakespeare is ‘universal’ come from? Why do people the world over study and perform Shakespeare? Colonialism. That’s where, and that’s why. Shakespeare was a powerful tool of empire, transported to foreign climes along with the doctrine of European cultural superiority.”

And here’s my own two-cents worth of view. Shakespeare groupies, including textual scholars and literary critics, argue that, in addition to its universality, the Bard’s language has influenced generations of English speakers, both native and adoptive. It is as if the words they speak today are his. “He continues to have”, as George Steiner explained and Cameron seemed to imply in his piece in Gulf News, “a mastering grip on our speech”.

But, you see, that’s the problem. Language is consciousness. Language is culture. It is linked organically to a felt reality and the evolution of our sensibility. Elizabethan English drew its idiom, no less than its manners of ceremonial exchange, from the perpetual social injustices that afflicted the age, as well as the imperialist ambitions and racist fantasies that later translated as The White Man’s Burden and La Mission Civilizatrice.

That weld of sensibility was later bequeathed to all manner of English Cold Warrior, counter-revolutionary and racist political leaders like Winston Churchill, and to the upper classes in British society like the insufferable Crawleys of Downton Abbey, whose odiously long dinners were attended to by docile “servants” resigned to their lowly socio-economic fate downstairs. The notion that “there is a place for everyone and everyone in his place”, lest we forget, came from Elizabethan England and was resonant in Shakespeare’s plays.

And, finally, I will disabuse groupies obsessed with Shakespeare’s “universality”, the seemingly trans-national, trans-cultural, trans-historical nature of his oeuvre, of their conceits by indulging in a recollection.

In the very late 1970s, I was invited by the American University of Beirut (AUB) to deliver a series of lectures on Comparative Literature — a course that included Shakespeare’s Macbeth. My students refused to take the play seriously, dismissing it as contrived and ludicrous. How could Lady Macbeth, they asked, extrapolating from their own Arab culture where the status of a guest is sacrosanct, plan to kill Duncan in her home (“The raven himself is hoarse that croaks the fatal entrance of Duncan under my battlements”). It’s absurd. It’s laughable. It’s just not done.

Thematically universal? Semantically cogent? Bill, get thee, along with your groupies, to a nunnery.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.