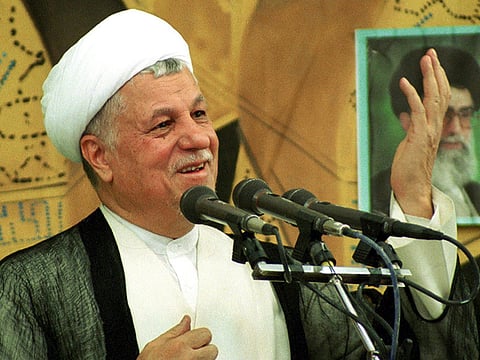

Rafsanjani stirs up a hornet’s nest in Iran

Leading pragmatist and former president’s statements on demilitarisation spark controversy as hardliners see red

The statements of Iran’s former president and the leading centrist figure, Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, which have been interpreted as a call for demilitarisation, have sparked controversy and prompted hardliners to launch a wave of attacks on him.

The remarks were made on August 10 in an education conference and surfaced in the media in the first week of this month. Rafsanjani had argued that “if today you see that Germany and Japan have the strongest economies in the world, it is because that after World War II they were prohibited from [having] military forces.” He added, “Having freed up the funds normally spent on costly military forces, these countries were in a position to allocate more money for scientific innovation and projects beneficial to their economies.”

The alarming part of the speech, as viewed by the hardliners, was where he said, “The path is now opened ... to enter such [a] climate and head in that direction. I am confident that [President Hassan] Rouhani’s second-term administration can get us there.”

Hussain Shariatmadari, the editor-in-chief of Kayhan newspaper, the mouthpiece of hardliners and Iran’s most well-known hardline newspaper, was quick to respond. “The statement by Mr Hashemi Rafsanjani is an invitation to America and other declared enemies of the Islamic Republic of Iran to attack our country.” He also asserted that Rafsanjani’s remarks were “a prescription for returning to a time of oppression, poverty, backwardness ... and for making Iran an obedient slave of America”.

Abdullah Ganji, managing editor of Javan newspaper, affiliated with the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), responded by saying that “the national honour of Iranians has been sold off in exchange for bigger bellies, although that also has not yet been realised”. He called for an “electoral revolution rather than holding [presidential] elections in 2017”.

In one of the latest reactions to Rafsanjani’s remarks, Amir Ali Hajizadeh, the commander of the Aerospace Force of the IRGC, said on September 7: “[First] have the guts to commute without bodyguards for a few days. Then claim that the country doesn’t need military forces.” Similar attacks will likely continue and gain in momentum in the coming days.

On his website, Rafsanjani’s office denied that he was suggesting Iran’s military should be downsized. The statement read: “Ayatollah Hashemi Rafsanjani’s statements were not meant to weaken [the country’s] military capabilities, or, as interpreted by critics, an invitation for the enemies to attack the country. Rather, they were an emphasis on the role of scientific and technological advancements in making the country immune from different kinds of harms, including the enemies’ greedy intentions.”

But what has made Rafsanjani’s hardliner opponents with close ties to the IRGC particularly suspicious is that he had made a similar move not long ago. On March 23, a tweet on Rafsanjani’s twitter page read: “The world of tomorrow is a world of dialogue, not missiles.” The timing of the tweet could have carried a special meaning, because on March 8, the IRGC test-fired two middle-range ballistic missiles that sparked uproar in countries with unfriendly relations with the Iranian government, including the United States.

A few days later, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei reacted fiercely, saying that those who believe the country’s future lies in negotiations rather than missiles are “either ignorant or traitors”. Not surprisingly, Rafsanjani’s initial tweet was revised and he said that his original remarks were improperly stated. The revised tweet read: “The world of tomorrow is the world of the discourse similar to the Islamic Revolution’s, not intercontinental ballistic missiles and atomic weapons.”

Two theories — or most likely the combination of two — can explain Rafsanjani’s moves.

First, Rafsanjani truly believes that a brighter future for Iran cannot be achieved through perpetual confrontation, especially with the US and its allies. Regarding his objection to hostile relations with America in the 1980s, in a hand-written letter to Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the Iranian Revolution, he clarified his stance when no one dared talk about a reconciliation with the US.

This viewpoint is not exclusive to Rafsanjani. This pragmatist school of thought shapes part of the Iranian establishment.

In meeting with American think tanks, academics and NGOs in September 2015, Rouhani asserted, “But for us to think that until the end of the world this animosity and tension between, and lack of relations between, the two countries will continue, that is an impossibility.”

In 2013, Mohammad Javad Zarif, Iran’s Foreign Minister, said the US could “wipe out Iran’s entire defence system with just one bomb”, leaving interaction and diplomacy as the only ways to resolve the issues that Iran has with the US. Zarif was obviously attacked by the hardliners and the military apparatus for his remarks.

Another explanation for Rafsanjani’s recent remarks could be that considering his popularity and given Iran’s struggling economy, he has calculated that the time is ripe to create and push for a discourse aimed at cutting military spending during Rouhani’s second term. Ultimately, his aim could be to weaken the military apparatus, primarily the IRGC — the pillar of power of the hardliners. The furious reaction from the hardliners is because they think that this explanation is actually his view, rather than a sincere miscalculation.

Shahir ShahidSaless is a political analyst and freelance journalist writing primarily about Iranian domestic and foreign affairs. He is also the co-author of Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace. You can follow him on Twitter at www.twitter.com/@SShahidSaless