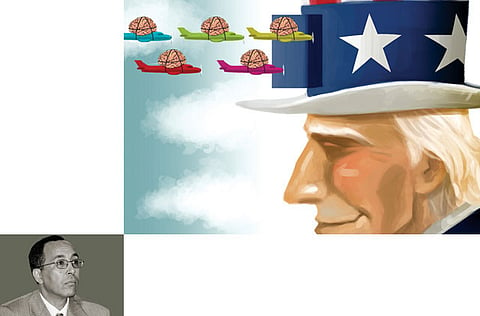

Plug brain drain by giving talent a chance to flourish

people need opportunities for professional, financial and personal development

Last month, an intriguing piece of news came up on my screen: A group of US senators asked for a ‘green card’ (permanent residency) fast track programme to be created for foreign students currently studying in the US in STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and maths).

They argued that many of the foreign students, who make up more than 40 per cent of MSc and PhD students in those fields, are not able to stay on in America after they graduate, and this constituted a threat to America’s future of technological innovation and industrial prominence in the world.

I then recalled an announcement that the Algerian minister of higher education made three years ago, when he stated that every Algerian student, who had received a scholarship for study abroad in the previous five years, had returned home.

Has the ‘brain drain’ tide been turned? I decided to investigate the matter.

Brain drain refers to the flight of highly educated people from under-developed countries to the West (which, of course, includes Australia and all developed countries). The phrase and the phenomenon have been well known for several decades now since large waves of migrations are occurring in different parts of the world for a number of reasons.

First and foremost, of course, is the fact that the more skilled people are, they more they want a comfortable and promising life — for themselves and their children. Well-educated people figure that their ‘brains’ can be a ticket to that better life. But there are other important reasons, including persecution (ethnic, political, religious, etc), and family reunions.

Developed nations have always benefited from this, so their state planners now discuss ‘brain gain’ and take steps to encourage the trend. Thus, similar to the above US senators’ special ‘green card’ initiative, the European Union recently introduced a “blue card” to draw in up to 20 million highly skilled workers from the developing world over the next two decades.

This kind of policy has had its unintended consequences, particularly with the rise of xenophobic nationalist parties in Europe, now regularly obtaining 15-20 per cent of votes on the basis of anti-immigration platforms.

Now, while some researchers try to find some positive aspects to the phenomenon, brain drain is overall quite bad and in some cases can be an utter disaster for a country.

For example, between 1980 and 1991, Ethiopia lost 75 per cent of its skilled workshop due to civil strife, and as the International Organisation for Migration recently noted, there are probably more Ethiopian doctors in Chicago than in Ethiopia itself and more nurses from Malawi in Manchester than in Malawi.

Recent studies have shown that overall brain drain rates have remained steady over the past few decades. One paper published by the World Bank in 2006 showed that a number of Arab-Muslim countries are still badly affected by the brain-drain phenomenon, particularly Iran, Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia, although the situation has improved substantially for these countries.

For these states, roughly one sixth of the highly educated workforce has emigrated to ‘greener pastures’.

Actually, as the adage goes, the grass always looks greener on the other side of the fence, and indeed there are scores of engineers and PhD holders who work as taxi drivers or shop employees in the West, and medical doctors who work as nurses in Europe (their degrees not always being accepted), but they still prefer that life to a job back home.

The cost of this can be staggering: The United Nations Development Programme estimates that Indian incurs losses of $2 billion (Dh7.34 billion) a year due to the migration of computer specialists.

Some analysts see some positive aspects for countries from where the brains are draining out; they point to the tens of billions of dollars made in remittances by the well-paid immigrants back to their home countries, to the positive effects on health, education, and general development that the remittances produce, and even to the fact that because many people want to emigrate, they will try to raise their skills and strengthen their résumés, but most will not end up leaving, so the net effect will be positive.

So what can be done about this phenomenon? Quick fixes don’t work. Some countries, e.g. Syria and Egypt, have in the past tried seizing the family properties of the students who are sent abroad to force them to come back. And, of course, contracts don’t bind those who are bent on leaving.

What needs to be done is to first improve the lot of the skilled local population by providing it with opportunities for professional, financial, and personal development in order to encourage talent to stay. In particular, the establishment of excellent universities, hospitals, and industries where the skills can be used and given a decent wage.

Secondly, make the educated diaspora part of the general development plan of the country. For example, appoint abroad-based experts to national commissions, to higher education boards, to industry planning and development committees, and to transparency and accountability agencies.

Brain drain is not going to disappear, certainly not in the near future. But it can be addressed intelligently to mitigate its bad effects and maximise the benefits that it may provide.

Nidhal Guessoum is an associate dean at the American University of Sharjah.