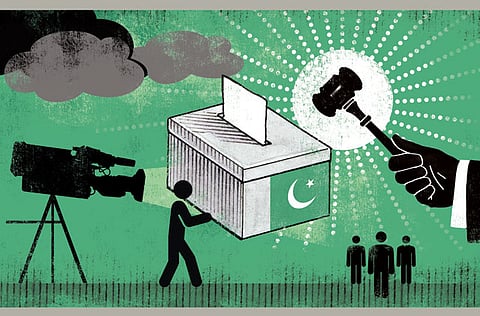

Pakistan has five reasons to hope

Landmark election proves that the pillars of democracy are still strong

As Pakistan prepared to return to the polls yesterday, dark clouds loomed. What should be a time of celebration for a country experiencing its first democratic transition in 66 years has turned into a sombre and strange moment of quasi-reflection.

Politicians and their families face the ongoing wrath of the Pakistani Taliban, as terrorists keep their promises of spilling the blood of openly anti-Taliban parties. Electricity in many parts of the country is in short supply, the treasury is near empty, and the government — unlike the Taliban — is unable to keep its promise of preventing terrorist attacks and ensuring security.

Meanwhile, tensions are surging on Pakistan’s border. To the West, Afghan and Pakistani forces exchanged fire in early May, prompting Afghan President Hamid Karzai to question the very nature of the border between the two countries, known as the Durand Line. On April 26, an Indian terrorist serving a life sentence in a Pakistani jail was beaten to death by inmates. Indian prisoners responded with a pick-axe attack on a Pakistani prisoner in an Indian jail.

Domestic tensions, and those with Afghanistan and India, probably won’t spin out of control, but still, life isn’t easy for Pakistani optimists. Despite it all — and this is Pakistan, so all is quite a lot — there are significant reasons to be hopeful. Here are the five biggest.

1. Feisty democracy

This first transition from one elected government to the next is a big deal, partially because Pakistanis are depressingly familiar with military interventions preceding power transfers. But it’s also important because Pakistan’s recent experience with democracy has been so unpleasant.

The word ‘democracy’ has become a tragic punchline in Pakistan, ever since President Asif Ali Zardari appealed to rioters reacting to his wife Benazir Bhutto’s December 2007 assassination by stating that “democracy is the best revenge”. Elected to succeed his wife, Zardari now oversees a notoriously inept government: His nominees for prime minister have all been investigated, indicted, or convicted for corruption.

Zardari’s government has also had to endure, in 2008 alone, the blowback from the Mumbai terror attacks, near bankruptcy, and a return to the International Monetary Fund for another $7.6 billion after the global financial crisis. Three years later, 2011 saw the Raymond Davis incident, the humiliating US raid to kill Osama Bin Laden, and the US-Nato attack on the Pakistani border post of Salalah that killed 24 Pakistani soldiers.

These stresses claimed many scalps, including former Pakistani ambassador to the US Hussain Haqqani, former foreign minister Shah Mahmoud Quraishi and former national security adviser Mahmoud Durrani. That’s not to mention several high-profile political assassinations — and many thousands dead from fighting.

To top it all off, in 2010, Pakistan experienced one of the most devastating floods of the 20th century, affecting more than 20 million people and marginalising the agrarian economies of the Pakistani heartland for almost a year.

And yet, after enduring these calamities Pakistanis are not only engaged in a major political debate about the future, but also likely to break records for voter turnout on election day.

What Pakistan has gone through since 2008 would have wiped out any chance of another free election in the Pakistan of the past. Yet there is now confidence and hope that not every government will be as feckless the last. Whatever the election result is on May 11, a young and fragile democracy is going to take a giant leap.

2. Activist judges

When then president Pervez Musharraf tried to fire him in 2007, Chief Justice Iftikhar Mohammad Chaudhry refused to go quietly into the sun. Like his predecessors, Musharraf had used the judiciary to help him discredit and imprison political opponents, and then disposed the judges that grow a conscience or chose a different team.

Instead of rolling over, Chaudhry fought back. He rallied some of the lawyers he knew, and within days, a movement emerged. Lawyers across the country gathered in support of a single cause: the reinstatement of Chaudhry.

Musharraf miscalculated the intensity of the fury that they were channelling - less around Chaudhry and more around the fatigue the country felt after eight years of Musharraf’s monotonous and ineffective rule.

Two years, one national emergency, millions of marchers, and a national election later, the chief justice was finally restored in March 2009. Since then, he has revitalised the judiciary by making it part of the daily national discourse. To do so, he’s taken on explicitly political cases, becoming a folk hero in the process.

Former prime minister Yousuf Raza Gilani, elected unopposed in 2008 - and, with a four year term, the longest serving PM in Pakistan’s history - was felled by Chaudhry after Gilani refused to reopen fraud investigations against his boss, Zardari. Chaudhry has repeatedly hauled in key officials suspected of corruption, cementing the Supreme Court’s status as a power centre.

Yes, Chaudhary’s model of activism is fraught with all kinds of political and institutional risk, and will contaminate the imagination of the next generation of Supreme Court judges, some of whom will seek to grab more power than Chaudhry currently wields. But his activism has helped create a vital venting mechanism for Pakistan.

In the Pakistan of old, Gilani might have been handed his walking papers by a general on a tank, illegally and unconstitutionally. The judges have found a way to challenge unbridled executive authority by bending the Pakistani constitution, rather than breaking it.

The most poignant sign of the judiciary coming of age is its treatment of Musharraf: The former dictator was jailed in April in the house he built to retire in. Once again, Chaudhry has showed Pakistan that the military is not above the law.

3. Freer media

Despite threats of violence from insurgents and terrorists, the media continues to hold up a remarkably candid and brutal mirror to the face of powerful Pakistanis — be they in uniform, robes, or the suits and shalwar kameez of politicians and businessmen.

For example, consider the outrage sparked in April after lower court judges rejected the candidacy of politicians because they didn’t seem “Muslim enough.” In came the journalists, pens and microphones blazing. Three days later, the hullabullo was over. Ten years ago, very few of those politicians would have had any advocates in the public discourse, and most would have been shouted down by obscurantists batting for those judges.

There is, of course, much room for improvement. Pakistan ranks 159th in Reporters Without Borders’ 2013 Press Freedom Index, just below Egypt. And on May 9, the major networks played, on incessant loop, video of people falling out of a burning building to their deaths. But that hunger for ratings and scoops is also what has produced a range of incredible acts of journalistic courage, all of which help sustain the status of the media as the steward of hope for a more free and pluralistic Pakistani public discourse.

4. Youth surge

More than 100 million of Pakistan’s 177 million people are below the age of 25 - and they’re referred to in Islamabad as a “ticking bomb.” Yet Pakistani youth are increasingly raised in cities, to families that can broadly be categorised as middle class. They are the apple of marketers’ and advertisers’ eyes; as regional and global telecoms and consumer goods manufacturers seek to expand beyond the Brics, they are coming to countries like Pakistan. Pakistani youth have access to the Internet, to mobile phones, and to the ideas and information these technologies bring.

And this election has become about them. Prime ministerial candidate Imran Khan, whose status as a Pakistani icon was sealed when he won for his country the cricket World Cup in 1992, became even more cherished when he raised money for the construction of Pakistan’s premier cancer hospital in the mid-1990s, as a memorial to the mother he lost to the disease. Despite accusations to the contrary, Khan has an excellent record of public service and integrity, which drives his appeal among youth. For 16 years, he peddled these qualities in a Pakistan whose politics was dominated by Benazir Bhutto and the pro-business Nawaz Sharif. And then something shifted. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly what it was - maybe the fatigue from the tired and broken rhetoric of the traditional parties. But in October 2011, more than 100,000 Pakistanis, many young and middle class, came together in Lahore to demand “change”.

Khan’s rhetoric has not changed since the 1990s. It is raw, simplistic, and incredibly powerful: He wants an end to patronage and corruption. The crowds Khan is drawing across all four of the country’s provinces are reminiscent of former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s cross-ethnic, cross-provincial appeal (though Bhutto didn’t deliver on many of his promises). Then, as now, a national leader rode to power on the back of young people. Khan may not win the election Saturday, but he is the trigger-man for an entire generation of Pakistan and its engagement with politics. Their continued and sustained involvement in the affairs of their country could help mold a Pakistan that holds itself accountable for its actions — internally and externally.

5. Indian thaw

Since the November 2008 Mumbai attacks, there has been a predictable hardening of opinion in India about what Pakistan represents: instability and violence.

But in Pakistan, India no longer represents the first, or even the second, most important villain. Sometimes, it’s no longer even seen as a public enemy. It could be because of a new preoccupation with the United States as the principal tormentor, or because of domestic crises unrelated to India. Perhaps most importantly, Pakistan’s elite have decided to prioritise trade and regional prosperity over disputes that neither country will outright win.

Consider the Pakistani reaction to events that have set the Indian national discourse on fire. In January, both India and Pakistan breached the uneasy border between the two countries. India was furious, particularly after accounts surfaced of Pakistani troops beheading an Indian soldier. A decade ago, Pakistan’s response would have been to reciprocate and escalate. But this time, Pakistan’s government and media barely responded at all, and Islamabad even offered India a UN investigation. Once India calmed down, tensions eased.

This is not to say that Pakistanis embrace their neighbour. They are still smart about India’s role in separating Pakistan from Bangladesh, and still view with acrimony India’s administration over large parts of Kashmir. Yet for all the bitterness and baggage, even the juiciest volleys from India are now returned with a disengaged “meh.” This will likely remain the status quo for a while. As long as it does, the doors remain open for India to tap into an unprecedented national appetite for normalcy.

No one will accuse Pakistan of being a model of tranquility. It remains shackled by security, economic, and political challenges. Things are not great in Pakistan, but they’re better than anyone could have expected. And at the time of a historic, if bloody, election, that’s worth remembering.

— Washington Post

Mosharraf Zaidi, a former Pakistani diplomat, advises governments and international organizations on public policy and international aid.