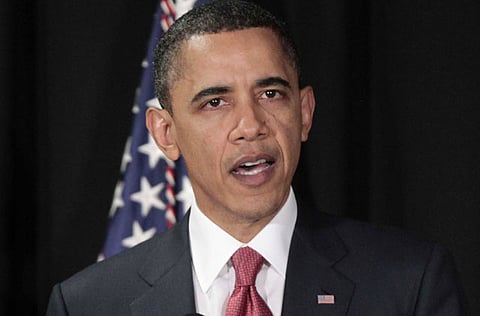

Obama's Middle East dilemma

Dr Marwan Al Kabalan writes: The US president has been paying lip service to the promotion of democracy in the region

When US President Barack Obama used the Cairo University as a platform to lecture the Arab world on the merits of democracy a couple of years ago, he did not imagine that his words and speeches would be tested before the end of his presidency.

In fact, Arab revolutions have put Obama and his political advisers off guard and have presented them with a dilemma that needs to be dealt with at some point.

In Tunisia, Egypt, Yemen and even in Libya, Washington seemed to have been quite content with the status quo.

It was forced to adjust its policy only when it became absolutely clear that change in these countries was inevitable. Several excuses have been given to justify the lack of interest by the Obama administration in democracy promotion in the Middle East.

Absorbed with his internal problems and preoccupied with re-establishing America's leadership abroad, Obama's utmost priorities are to resuscitate the US economy and end two unnecessary wars in the greater Middle East, i.e. Iraq and Afghanistan, it has been argued.

Given the golden opportunity presented by the uprisings in the Arab world to advance the cause of democracy, however, these excuses are hardly convincing. Unlike the costly intervention in Iraq, for example, the US could contribute to establishing democracies in the Arab world at a cheap price.

Over the past two years, since he became president, Obama has not been really interested in the kind of rhetoric which featured prominently under his predecessor and focused on democratic change in the Middle East. Words such as ‘democracy promotion' have almost disappeared from Obama's public speeches. This trend brought to the fore the eternal question in US policy circles about the ability of America to live with democratic governments in the Middle East.

Shah experience

The thesis that America must support dictators or else accept to live with the very people it regards as dangerous for its interests and core values has become the compass that directs US policy in the Middle East under Obama.

His dilemma in dealing with the current events in the Arab world involves balancing the desire for establishing democracy with the risk of losing power to anti-US elements. His worry is that democracy in the Middle East may very well empower the very forces that the US opposes, i.e. Islamists.

Clearly, the US is still hostage to its unfortunate experience in Iran. Americans still remember with bitterness that in the 1970s when former US president Jimmy Carter demanded that the Shah should respect human rights, the domestic pressures that were unleashed helped overthrow his rule and bring about an Islamist government. The US cannot hide its fear of having similar experiences in the Arab countries where revolutions are taking place.

This prevalent view among US officials explains the hesitancy and the inconsistent policies of the Obama administration concerning Arab revolutions.

Right now Washington believes that Arab governments should heed the call for democracy at their own pace, otherwise America might end up rocking the boat too much.

Indeed, the Arab world has long moved ‘at its own pace' towards democracy. The result was almost no democracy at all. Until recently, this state of affairs seemed to have suited the US fine, because it was easier to deal with dictators than politicians worried about re-election.

Furthermore, there seems to be an attempt, as can be seen in the Obama administration's public statements, to set up the entire debate about democracy promotion in such a way as to make criticism particularly difficult — i.e. how can anyone be against gradual and peaceful transition from autocracy to democracy in the Arab world? Bearing in mind the Iraqi experience, how can anyone support a military intervention by the US in countries where atrocities are committed by regimes against their own people?

Inconsistencies

Under any circumstances however, it is difficult to prove that democracy promotion would be at the centre of US foreign policy, despite Obama's claim to the contrary. It seems also difficult to conclude anything other than that promotion of democracy in the Middle East was and remains a tool among many to promoting US interests rather than an end in itself.

Under the Obama administration, the pro-democracy rhetoric will be almost certainly overused by clear inconsistencies, as we have been witnessing since the outbreak of the Tunisian revolution.

In light of what has been said, it is believed that the Obama administration's commitment to democracy promotion is more of a public relations ploy than anything else. The reaction to the pro-democracy movement in the Arab world testifies to this fact.

Dr Marwan Al Kabalan is lecturer in Media and International Relations at Damascus University.