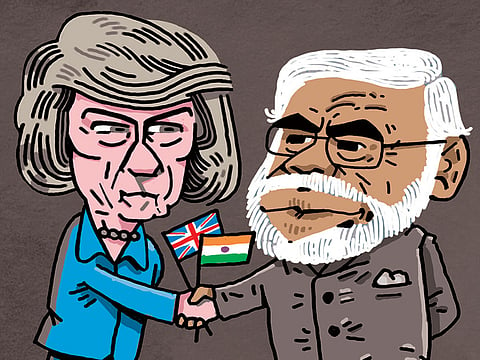

May-Modi meeting puts economic ties first

Irritants in UK-India relations will continue to be overridden by the depth of bilateral economic collaboration and strength of historical political connections

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi finished up on Friday a five-day European tour after meeting, briefly, with Chancellor Angela Merkel in Germany. With his trip starting in Sweden for an India-Nordic summit, the highlight was the United Kingdom leg of the visit where he and UK Prime Minister Theresa May announced around £1 billion (Dh5.24 billion) of new business deals in London.

Modi’s landmark UK visit, only the second tour to the nation by an Indian premier for over a decade, highlights the uptick in bilateral bonds, and has strengthened political and economic ties. Modi had a number of high-level meetings including with May, Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Charles.

Yet, while the visit saw top-level UK access, and a separate Q&A style televised session with 1,500 members of the Indian diaspora in the UK, it was not as high-profile overall as his 2015 pre-Brexit visit. It was then that he gave an “Olympics-style” address at Wembley Stadium at one of the largest receptions for a foreign head of state ever in Britain, and also the largest ever event outside India ever attended by one of the country’s premiers.

Both May and Modi attach high importance to the bilateral relationship, not least given Indian’s long historical ties with the UK and the estimated million-and-a-half Indian diaspora population in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. May has already visited India during her premiership and wants UK firms, post-Brexit, to gain stronger access to the Indian market of around 1.3 billion consumers through a new UK-India trade deal.

The strength of the contemporary economic relationship is underlined by the fact that, according to the Confederation of British Industry, the UK has already invested more than $22 billion (Dh80.91 billion) in India since 2000, making it one of the biggest G20 employers and investors in the country. India, meanwhile, is one of largest sources of foreign investment in the UK.

For the Indian premier, encouraging international investment, via the City of London, to finance Indian infrastructure is another key priority. This builds on the announcement made during Modi’s last trip over the sale on the London Stock Exchange of rupee-denominated offshore “masala-bonds” to finance infrastructure investment, including in Indian housing and railways.

In addition, Modi and May launched the India-UK Tech Alliance comprising young CEOs from the two countries, and also promoted support for the Digital India initiative which aims to ensure that government services are made available to citizens electronically by improving online infrastructure and by increasing Internet connectivity. To this end, he made clear that he seeks further telecoms and technology investments in India by UK-headquartered firms.

One of the other key economic issues Modi pressed for is UK immigration reform to enable more Indian business people and students to travel to Britain. This may be made easier by the agreement between London and New Delhi on swifter return of illegal Indian immigrants, which had been a vexed issue repeatedly raised by the UK Government.

A related opportunity discussed by Modi and May is the possibility of formal Indian recognition of one year UK-based Masters degrees that are secured by around 14,000 Indians students each year. Currently, New Delhi does not fully recognise these Masters programmes, given that the duration is double in India for similar degrees.

Despite the overall positive diplomatic mood music of the trip, a number of political irritants remain in bilateral relations. For instance, there was a debate in Westminster earlier this Spring in which members of parliament asked that May raise with Modi the treatment of Sikh and Christian minority groups in India, and various groups — including the Sikh Federation UK — protested on Wednesday.

That recent Westminster debate follows up on a 2015 motion signed by around 40 MPs, calling on then-premier David Cameron to raise human rights issues with Modi. Moreover, in 2013, there was also a UK parliamentary motion calling on the Home Office, which is responsible for immigration policy, to reintroduce a UK travel ban on Modi, citing “his [alleged] role in the communal violence in 2002” in the Indian state of Gujarat. Under this ban, which was rescinded in 2012, the now-prime minister was not allowed to enter the UK due to his alleged involvement in massacre of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002 when he was the state’s chief minister. Modi has also been accused of failing to stop anti-Muslim rioting in 2002, which led to the deaths of at least 1,000 people in Gujarat.

Despite these continuing controversies, however, Modi’s visit has warmed bilateral ties with numerous key business deals and wider initiatives announced. Irritants in UK-India relations will continue to be overridden by the depth of bilateral economic collaboration, and strength of historical political connections.

Andrew Hammond is an Associate at LSE IDEAS at the London School of Economics.