‘Invisible primary’ is invisible no more

One of the few certainties of the coming American campaign is that it will be far more expensive than the last

Hillary Clinton’s campaign may raise and spend as much as $2 billion (Dh7.35 billion) over the 18 months between now and the next US presidential election. The shocking thing is that no one seems particularly shocked by this fact. The only reason no one on the Republican side is talking about spending that kind of money is that in a large and growing field of GOP candidates, no single contender seems likely to be able to corner donors’ cash to nearly the same extent.

Over the last few years, a series of US Supreme Court rulings have equated money with speech, declared that corporations have the same right to donate to candidates as individuals, narrowed the definition of bribery to a point where it is now essentially meaningless and largely eliminated caps on how much wealthy individuals can donate to candidates.

What all of this means is that 21st century American politics is not too far removed from 19th century American politics — an era in which campaign finance law essentially did not exist, it was considered more or less normal for rich people to hand candidates suitcases filled with cash and those rich folk, in turn, spoke openly of “owning” politicians. On a purely theoretical level nearly everyone who follows American politics is worried by this trend (or at least professes to be worried). In practical terms no one who is part of the system believes it will change any time soon.

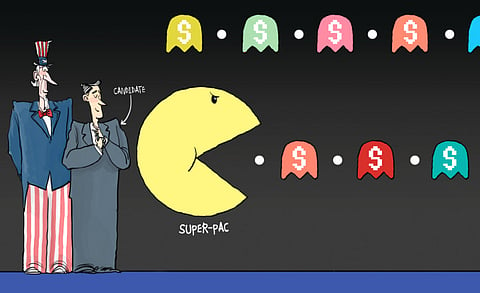

For example: The complexities of American election law allow so-called “Super-PACs” to collect unlimited funds from donors, keep the names of those donors secret and spend the money however they wish provided there is no “direct coordination” between the Super-PAC and a candidate’s official campaign.

“Coordination”, however, is very narrowly defined. In one of the more memorably comic moments of last year’s mid-term campaign, Senator Mitch McConnell posted all of the video clips one might need to assemble campaign commercials on his official website along with a note that these clips were available for public use. He did not ask the Super-PACs supporting him to turn the clips into campaign ads. Such a request would be illegal. It was also unnecessary. It was obvious why the clips were there and they duly turned up in pro-McConnell adverts within days. Thanks to Jon Stewart highlighting them the clips also turned up in many, many home-made parodies that circulated around the internet for weeks.

In 2012 Mitt Romney got around the ‘coordination’ ban by having his top aides — people already intimately familiar with his thinking and campaign strategy — set up and run a Super-PAC supporting him after nominally severing ties. It was reported last week that former Florida Governor Jeb Bush is considering taking this a step further in 2016 by letting a Super-PAC run by his closest advisers take over almost every aspect of his campaign other than Jeb’s own travel and appearance schedule. Once Jeb’s campaign formally begins, they and he will not be able to contact one another. The point is that they will not have to. These are people who already know exactly what Bush wants them to do. Any change in strategy can be conveyed to the aides entirely legally if it comes in the form of a public statement or even a tweet (“I wish the people supporting me would pay more attention to ...”). In the meantime, because Jeb is not yet formally a candidate, he is busy raising money for this same Super-PAC.

Meanwhile, most of Bush’s Republican opponents spent last week in Las Vegas courting the favour of Sheldon Adelson, a casino billionaire who spent an estimated $100 million on the 2012 campaign (mainly funding Newt Gingrich’s quixotic campaign) and is thought to be willing to fork over much more this time around to the candidate who most closely channels his right-wing views on Israel. A similar GOP frenzy surrounds efforts to win the favour of Charles and David Koch, billionaire brothers who have indicated that they may spend more money than either of the two actual political parties to elect their preferred candidate — someone who shares their philosophy of not regulating industry and helping big business crush labour unions.

Democrats are different only insofar as there are far fewer liberal billionaires out there looking to ‘invest’ in political candidates and the few who do exist seem mostly willing to take their promises of fealty in private rather than demanding public grovelling by candidates.

This struggle for early money used to be known as the “invisible primary”. Invisible, because it used to take place well out of public sight. Winning it was what allowed George W. Bush to clear the field of most serious rivals long before any votes were cast in 2000. It was what convinced John Kerry that he was well on his way to the Democratic nomination in 2004 even when Howard Dean was drawing all of the media attention. Doing well in it does not guarantee victory, but it can keep some candidates in the running long after common sense and a lack of primary victories would argue they should be gone (Gingrich and Rick Santorum in 2012). That the invisible primary now takes place largely in plain sight is a sign of the degree to which the link between money and politics has become a normal fact of American political life.

It is hard to argue that this system is good for democracy (though some, mainly on the Right, do indeed make that case). In the meantime, one of the few certainties of the coming campaign is that it will be far more expensive than America’s last — though probably somewhat cheaper than the next presidential election in 2020.

Gordon Robison, a longtime Middle East journalist and US political analyst, teaches political science at the University of Vermont.