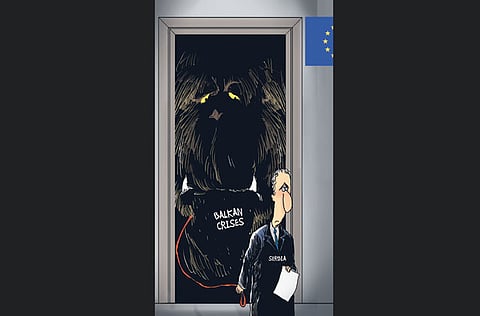

Ignoring Serbia will not help

The great importance of Serbia's application for EU accession is that it could bring about successful and permanent reorganisation of the Balkans

Serbia's government formally submitted its application for European Union (EU) membership just before Christmas. A few days earlier, visa requirements for the country's citizens were lifted, together with those for citizens of Montenegro and Macedonia. The exultation about this step was great in all three of these countries; their expectations of the EU are even greater now.

Reactions in Europe, by contrast, were meagre or non-existent. Public sentiment towards EU enlargement is negative. In fact, a majority of states and citizens would prefer to stop enlargement the most important and effective means by which Europe is capable of projecting power once and for all. Anonymous senior diplomats in Brussels were quoted as regarding Serbia's application to be too early; otherwise, an embarrassing silence prevailed.

Exhausted by the frustrating climate negotiations in Copenhagen, European leaders seemed not to be in the mood for questions about EU enlargement. Indeed, given the domestic political mood in the 27 member states, they are deeply convinced that discussing further enlargement would win them no bouquets.

As a result, a subjective twilight is lowering over the European project. That is tragic, because many unique and even historic opportunities are not being seized. Serbia's application for accession is precisely such an opportunity.

It was Serbia, Yugoslavia's largest federal unit, which, led by Slobodan Milosevic, triggered the great Balkans crisis and caused numerous wars and ‘ethnic cleansings' as the federation collapsed at the start of the 1990s. Under Milosevic, a majority of the Serbs turned to radical nationalism based on violence and territorial conquest.

Four wars — in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo had to be fought and a fifth one in Macedonia had to be prevented at the last minute by Nato and the EU in order to put violent Serb nationalism in its place. With the defeat in Kosovo, Milosevic was finally thwarted.

Still, throughout this time, integrating Serbia into the region's post-nationalist order remained central to the West's strategy. Certainly by the time of the West's military intervention in Bosnia, this strategy was based on the assumption that the European continent after the end of the Cold War should not allow itself to have a divided security system — that is, if security and peace were to be permanent.

This meant that the Balkans, too, had to be introduced to Euro-Atlantic structures first and then integrated into Nato and the EU, because only a new European order could overcome the region's recurring tragedies and guarantee lasting security.

Serbia played and plays a central perhaps even the leading role in this. For Serbia's path to Europe will immediately enable resolution of the main Balkan crises and conflicts that continue to this day: Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, and war criminals.

Without addressing the question of its final borders, however, Serbia has no prospect of joining the EU. The Europeans have gained experience with Cyprus. They will not let another state into the EU whose border issues are not resolved beyond any doubt. And, in Serbia's case, this question remains open regarding Kosovo and in a more concealed way Republika Srpska in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Serbia must also deliver General Ratko Mladic, who led the Bosnian Serb army during the Balkan wars, to the war crimes tribunal in The Hague or prove that he is dead or hiding elsewhere. Mladic, whose troops carried out atrocities throughout Bosnia and Herzegovina including the massacre of thousands of Muslim civilians at Srebrenica in 1995 is the most significant war-crimes suspect still at large since former Bosnian Serb president Radovan Karadzic's arrest in Belgrade and extradition to The Hague in 2008.

Opportunity

Nevertheless, the great importance of Serbia's application for EU accession is that it could bring about successful and permanent reorganisation of the Balkans. To be sure, the path to accession will be tiresome and long, but if both sides set out on this path decisively and sincerely, the whole region will be changed for the better.

Europe stands only to gain from continued accession negotiations over Serbia. Bringing Serbia into the EU would permanently stabilise the regional order and at the time when Europe is increasingly wary of indefinite military commitments offer the prospect of a concrete exit strategy for Nato troops in Kosovo.

But this assumes that the governments of EU member states finally accept their political responsibility and, instead of pandering to rampant enlargement fatigue, take decisive steps against it.

Europeans may be too tired and divided to play a significant role in world politics, which could have dire consequences for Europe in this time of global realignment. But even if Europe abdicates its global role, the EU cannot forget about order within its immediate neighbourhood, or hope that others will solve their problems for them.

The Balkans are a part of Europe, and Europeans must solve the region's problems. Serbia's application for EU accession provides a historic opportunity to achieve just that.

— Project Syndicate/Institute of Human Sciences, 2010