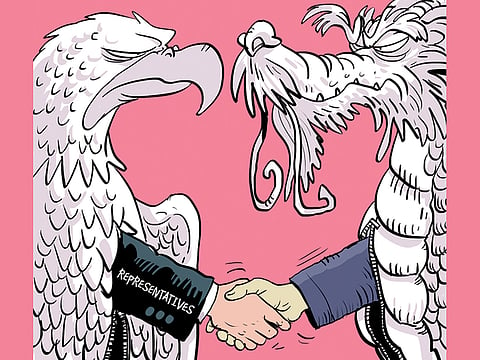

How to avoid a Sino-American war

For Chinese policymakers, the United States is not the status quo power it claims to be

In a few weeks time, senior US and Chinese leaders will sit down in Washington for their annual “strategic dialogue”. Given rising tensions in the South China Sea, that dialogue is taking on increasing importance.

In 2001, when an American EP-3 spy aircraft operating over the South China Sea collided with a Chinese air force interceptor jet near Hainan Island, Chinese and US leaders managed to defuse the situation and avoid a military confrontation.

Today, such an incident in the South China Sea, where China and several south-east Asian countries have competing territorial claims, would almost certainly lead to an armed clash — one that could quickly escalate into open war.

Last month, at the annual Shangri-La Dialogue security conference, Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong conveyed the deep apprehension of the countries of the Association of South-east Asian Nations (Asean) about the potential for an armed conflict between China and the United States.

The good news is that US and Chinese representatives took the conference as an opportunity to signal subtly their willingness to ease tensions and continue to engage with each other.

US Secretary of Defence Ashton Carter, in an effort to limit the scope for provocation, called on all claimants to territories in the South China Sea to stop island-building and land-reclamation efforts there. He also proposed a regional security architecture that gives all countries and people in the Asia-Pacific region the “right to rise.”

From China’s side, Admiral Sun Jianguo, a deputy chief of staff of the People’s Liberation Army, reiterated his country’s commitment to resolving disputes through “peaceful negotiations, while preventing conflicts and confrontation.”

He added that all countries, big and small, have an equal right to participate in regional security affairs and share a responsibility to maintain regional stability.

But such mollifying rhetoric cannot obscure the defining role that great-power rivalry is playing in the South China Sea. China interprets US intervention there as an explicit attempt to contain China by stoking conflict between it and its neighbours. The US views China’s maritime claims as an effort to challenge US primacy in the Asia-Pacific region.

In a sense, both countries have a point. China does aspire to be a maritime power, but its coasts are, to some extent, encircled by Japan and the Philippines, both US allies, and Taiwan, with which the US maintains security ties.

But strategic mistrust between China and the US extends far beyond maritime issues. Despite troubling situations in the Middle East and Eastern Europe, America has remained focused on reshaping its hub-and-spoke alliances into a more networked security system across the Indo-Pacific theatre, capitalising on the web of intra-Asian military ties among old allies and new partners such as India and Vietnam.

In particular, the US-Japan alliance is undergoing historic transformation, with renewed guidelines for defence cooperation that allow for greater Japanese autonomy in security affairs — and that present China as the main adversary. Add to that the potential deployment of a US-led missile-defence system in South Korea and the prospect of a US military presence in Vietnam, and it is not difficult to understand China’s anxiety.

The US is placing economic pressure on China as well — at a time, no less, when China is struggling to implement risky domestic reforms amid slowing growth. The US recently attempted to block the establishment of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, and then to stop its allies from joining.

Moreover, by repeatedly calling the proposed Trans-Pacific Partnership a “strategic” project, it has politicised the trade deal, which, as the economist Arvind Subramanian has pointed out, will place Chinese firms at a disadvantage in the US and in Asian markets. This effort undoubtedly deserves to be described as “containment.”

For Chinese policymakers, America is not the status quo power it claims to be. In the face of US attempts to reshuffle regional security and economic arrangements, China feels that it has no choice but to prepare for worst-case scenarios — an approach that is reflected in Chinese President Xi Jinping’s so-called “bottom-line concept.”

With a new round of policy debate about China unfolding in the US, tensions may be about to increase. Most American strategists are not only pessimistic about the future of the bilateral relationship; they also identify China as a potent threat to America’s role in Asia.

A recent report for the relatively moderate Council on Foreign Relations states that America’s effort “to ‘integrate’ China into the liberal international order” has generated “new threats” not only to US primacy in Asia, but also to America’s global power. Given this, the report’s authors argue, the US needs “a new grand strategy” toward China that focuses on balancing — rather than supporting — the country’s ascendancy.

Michael Swaine, a seasoned Asian security expert at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, also doubts the sustainability of American primacy in the Asia-Pacific region in the coming decades. He advocates a less antagonistic strategy: a multi-stage process of mutual accommodation to create a more stable regional power balance between the US and China.

Ensuring stable peace and continued prosperity in the Asia-Pacific region will require both China and the US to replace their self-serving interpretations of the other’s strategic intentions with more sober assessments. In the short term, that means recognising that the challenge of navigating complex maritime issues involving so many ambitious regional players must be addressed in a pragmatic and cooperative manner.

By activating top-level diplomacy, building strong crisis-management mechanisms, and enriching the rules of engagement in the South China Sea, a war between the US and China can be avoided. Given the vast damage that such a conflict could cause, this approach is less an option than a necessity.

— Project Syndicate, 2015

Minghao Zhao is a research fellow at the Charhar Institute in Beijing, an adjunct fellow at the Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies at Renmin University of China, and a member of the China National Committee of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific (CSCAP).