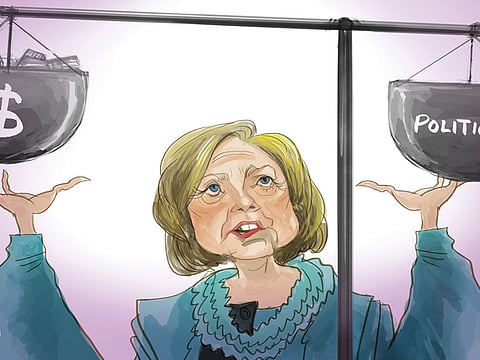

Hillary Clinton’s conflict-of-interest problems

A successful candidate needs to reassure voters that she can reduce the impact of money in politics

The harshest charges against Hillary Rodham Clinton — that she made decisions that favoured donors to her family’s charitable foundation when she was secretary of State — aren’t sticking. Yes, the Obama administration approved a donor’s sale of US uranium mines to a Russian firm, but Clinton does not appear to have been involved.

Yes, the administration concluded a trade treaty with Colombia that benefited Clinton Foundation donors, but that was President Obama’s decision, not Clinton’s. And yes, Clinton lobbied foreign governments on behalf of donors such as General Electric and Boeing — but that’s part of every secretary of State’s job description.

Still, that doesn’t mean candidate Clinton has emerged unmuddied from the swamp of accusations and innuendoes stirred up by conservative author Peter Schweizer in a book scheduled for publication this week. The front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination still has some explaining to do.

When she was nominated as secretary of State in 2009, Clinton promised that she would bend over backward to avoid potentially compromising situations.

“Out of [an] abundance of caution and a desire to avoid even the appearance... of a conflict,” Clinton said, the foundation would agree to strict rules: It would disclose all its donors and clear new contributions from foreign governments with the State Department.

Only that didn’t happen. The biggest branch of the Clintons’ charitable network, the Clinton Health Access Initiative, never complied with the agreement at all, according to the Boston Globe. It neither disclosed its donors nor cleared new contributions. (A spokesman said they didn’t think it was necessary. After media inquiries, the program published a list of donors last month.)

The Clinton Foundation also failed to clear a donation of $500,000 (Dh1.83 million) from Algeria. (An oversight, the foundation said.) And the foundation’s Canadian affiliate collected millions of dollars without disclosing donors’ names. (Canadian law guarantees privacy to donors, but the foundation could have asked them to voluntarily disclose their identities; it didn’t until last week.)

Beyond the Clinton Foundation and its affiliates, former President Bill Clinton’s personal income has raised eyebrows, too.

Thanks to the Washington Post, we have learnt that Bill Clinton made almost $105 million giving speeches from 2001 to 2012 — and his biggest fees came from foreign hosts while his wife was secretary of State: $1.4 million from a Nigerian media firm (for two visits to Lagos); $750,000 from the Swedish telecommunication giant Ericsson; $600,000 from Dutch financial firm Achmea; and $500,000 from Renaissance Capital, a Russian investment bank with ties to Vladimir Putin’s Kremlin.

The former president did take one sensible precaution: He cleared his speech gigs with State Department ethics lawyers. According to records obtained by the gadfly group Judicial Watch, the lawyers approved every one of the 215 speeches that were proposed.

There’s nothing illegal about any of that; other former presidents have accepted giant speaking fees, too. Ronald Reagan once picked up $2 million for a trip to Japan — and that was in 1989 dollars.

But there’s nothing pretty about that picture, either. Even though the lawyers approved the deals, dozens of the firms that paid Bill Clinton were doing business with the US government at the time. Surely Hillary Clinton’s 2009 promise to avoid “even the appearance” of any conflict of interest should have applied to her spouse as well as the family foundation — right?

The Clinton Foundation has taken one step in the direction of reform: It said it would stop taking money from most foreign governments while one of its namesakes is running for president. For the most part, though, Clinton has tried to deal with bad press by either ignoring it or deploying underlings to attack her critics.

That’s not going to work; Clinton’s problems won’t just go away.

A successful candidate, at least in the Democratic primaries, needs to reassure voters that she can reduce the impact of money in politics and restore confidence in government. Right now, Clinton can’t do that credibly.

And Clinton’s conflict-of-interest problems will dog her in the debates that will begin in August. “The Clinton Foundation ... that’s a fair issue,” Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont said Thursday as he announced his candidacy. (The bigger issue, he added, is “the huge amount of money it takes to run a campaign.”)

Hillary Clinton can’t undo the past. But here are four things she can do to improve the situation now: She can press the Clinton Foundation and its affiliates for disclosure of all donors, in belated compliance with the agreement they made in 2009. She can ask the foundation to tighten its limits on foreign donations — for example, to cover individuals with close ties to foreign governments.

She can ask her husband to tighten his criteria for speaking fees, too, and make it clear that he’ll donate his biggest pay cheques to charity. Most important, she can spell out the rules she expects her family to live under if voters decide to put her in the White House.

Last week, I asked the Clinton campaign if they saw merit in any of those ideas. I haven’t heard back.

Los Angeles Times