Exposing Africa’s elusive Kony

Among warlord's excesses, his forces have abducted 66,000 children and abused them until they served as soldiers

Where the devil, you ask in despair as you dust off that atlas off the shelf, is the Central African Republic, and why have the stone-age tactics of one of the region’s warlords, the messianic Joseph Kony, who is believed hiding in the country’s dense jungle, helped him elude the high-tech tools deployed by the most advanced nation on earth to capture him, or ideally “eliminate him with extreme prejudice”?

But, hey, this is sub-Sahara Africa and the rules here are different. So let’s backtrack a bit.

“Seek ye first the kingdom and all else will follow”. This facile piece of divine wisdom was proffered in 1957 to the newly independent African countries by Ghana’s first head of state, Kwame Nkrumah, who went on to become a founding member of the Organisation of African Unity and who — along with Indonesia’s President Sukarno and Egypt’s President Jamal Abdul Nasser — dominated the then wildly popular, but ineffectual and now defunct, Non-Aligned Movement.

Decades after the fact, the number of true ‘kingdoms’ in sub-Saharan Africa could be counted on the fingers of one hand and the ‘all else’ that was to be reaped from their establishment turned out to be ‘little else’ than misery and destitution. Civil wars, massacres and famine became the norm, spawning the world’s largest refugee problems. Military coups were the standard for changing national leaders, who relied on coercion, rigged elections and absolute power to rule, and regarded revenues of the state as their personal piggy-bank.

At the end of the 1990s, according to the World Bank, per capita income was lower than it was in the 1970s. Seventy per cent of the poorest nations in the world are in Africa. And by now we have ceased to turn in nauseated disbelief at the spectacle of hungry children with swollen bellies or at the continent’s endless wars, mayhem and human pain. Only when these catastrophes reach a point beyond all rational understanding — when the body count climbs to the tens or hundreds of thousands, and the suffering becomes unendurable — are we nudged into action and we send in the boys from Medecins sans Frontieres and those from U2, including the well-meaning Bono. Sometimes former colonial powers and the US, the global goody-two-shoes, will send in a military contingent or two to see what they could salvage.

Crimes against humanity

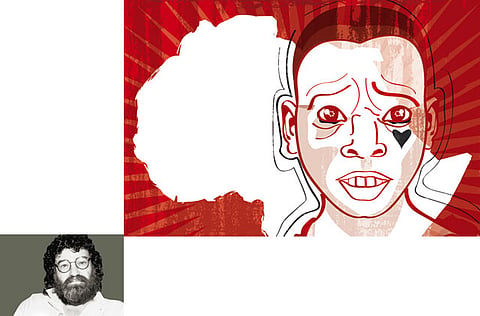

All of which brings us to Joseph Kony, a native Captain Kurtz of sorts, whose brutalities were highlighted in a half-hour documentary by the group Invisible Children, that went viral on YouTube, watched by millions. The 54-year-old Kony, along with his militia forces, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA), has operated in his native Uganda, as well as South Sudan, the Congo and the Central African Republic, where he is now holed up. The man would be dismissed as strictly loony-tunes were he not so barbaric. He considers himself a medium visited by a host of spirits from several countries, including a Chinese phantom, and God’s own spokesperson, whose mission is to “purify” the Acholi people and establish for them a state based on the Ten Commandments.

To that end, his militia forces have, since 1987, abducted roughly 66,000 children, and beat and abused them until they served as soldiers. He has wrought horrific violence, including rape, murder and banditry, on villages across the region his group operated from. In 2005 the International Criminal Court in the Hague indicted him for war crimes against humanity.

Six months ago, US President Barack Obama ordered 100 elite troops, chosen from the Green Berets and Navy SEALS, to help capture Kony, but they have been unable to pick up his trail. Since, these troops have fanned out to five outposts, advising thousands of local troops on how to hunt for him. The remote territory is reportedly the size of California, where even dirt roads are scarce and dense jungle enables members of the LRA to escape capture by slipping deeper into the bush in a region encompassing territories across Uganda, South Sudan, the Central African Republic and the Congo.

Especially the Congo, that old stomping ground of Joseph Conrad’s characters, including the renegade Captain Kurtz, in The Heart of Darkness, a novella considered part of the western world’s literary canon, much as Francis Ford Coppola’s film Apocalypse Now, adapted from it, has become a part of American cinematic art. There is no other work of literary imagination, set in Africa, that so searingly exposes, as this work does, the dark side of European colonisation, as it equally explores the darkness of the Congo wilderness, the darkness of the Europeans’ inhuman treatment of Africans, and the darkness — often inexplicable, unfathomable and immeasurable — that lurks within every human being, a darkness that propels us all to commit evil, in places as disparate and as far apart as Nazi Germany and Khmer Rouge Cambodia.

So what, in the end, is the evil committed by this man called Joseph Kony compared — were we able to quantify evil — to the evil committed by, say, King Leopold of Belgium in the Congo Free State between 1885 and 1908, who established a system of forced labour that kept the natives in a condition of slavery, a condition whose end result was death, according to King Leopold’s Ghost (1998), the definitive work on the subject, by Adam Hochschild, of roughly 10 million people. And how many other Africans have perished, under other European colonial rulers, in other African countries?

Though the brutalities committed by Kony’s militia forces are not to be excused or belittled, the African Joseph Kony is but a tin-eared, two-bit, bone-head leader, a mere importunate scarecrow when measured up against the European King Leopold, and other colonial beasts, whose excesses were intensely expressive of the cruel spirit of the colonial age.

And that is why Europeans today want to help Africans when Africans suffer at the hands of the likes of Charles Taylor, Idi Amin, Laurent Gbagbo, Muammar Gaddafi, Jean Pierre Bemba and now Joseph Kony. By helping Africans in need, Europeans get to hammer out some kind of inner compromise with themselves, taking a punitive foray into their conscience. Then from once having been the venomous louse in the body of colonised culture, they now emerge as the chastened promoters of its people’s human rights. Fine, let’s say no more, for the issue is too capacious for any single political column to explore.

And, Bono, please, lose the designer shades when you hit the African heartland on your next trip there.

Fawaz Turki is a journalist, lecturer and author based in Washington. He is the author of The Disinherited: Journal of a Palestinian Exile.