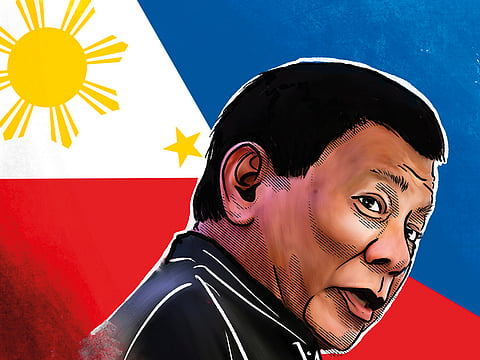

Duterte mellows in style but not in substance

Critics of the Philippines president wonder if he can sustain his political survival

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte has shown signs of mellowing in style but not in substance, making fans and critics more curious about his balancing act aimed at ensuring his political survival. He needs to remain popular if he wants to get his two pet projects ratified: a legislated law that will implement controversial provisions — shared economy and power, and an expanded autonomous region — in the peace settlement signed with the 40-year-old Moro Islamic Liberation Front; as well as the proposed shift from a unilateral (presidential) to federal form of government.

The people’s approval of these two measures will test Duterte’s endurance. The proposed law for Filipino-Muslim autonomy is expected to be approved by five million people in their turf in the southern Philippines. A survey done by private Pulse Asia has shown that nationwide, only 5 and 3 per cent want federalism and charter change, respectively.

At the State of the Nation Address (Sona) recently, Duterte vowed not to give up his relentless campaign, which started in mid-2016, against the illegal drug trade, a campaign that has made him south-east Asia’s strongman.

In contrast, rights-oriented Filipinos, the majority of whom are Christians, are intensely pushing for an end to the killings.

Duterte sees the drug menace as a social cancer — it has tainted his country as a narco-state with powerful officials on the take. The police said the campaign has resulted in the deaths of more than 4,000 since mid-2016. Rights groups claim 23,000 were victimised.

Many recall Filipino-Chinese drug lord Lim Seng who was executed by firing squad in Metro Manila’s Fort Bonifacio, a military base, after former strongman Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law in 1972.

Capital punishment was available for Marcos in 1972 — it was allowed by the constitution from 1946 running into the mid-80s. Congress abolished it in 1987 during the time of former president Corazon Aquino, re-imposed it in 1993 during the era of ex-president Fidel Ramos, repealed it in 2006 during the rule of former leader Gloria Arroyo, and re-imposed it for drug offenders only in 2017, in Duterte’s second year.

No drug lord has been executed since 1972 and Duterte’s leadership has yet to implement the death sentence against a drug lord.

The president is being praised for ousting half of his 22 Cabinet officials following alleged corruption issues, But Pulse Asia’s June survey said only 26 per cent of Filipinos nationwide support the campaign against illegal drugs, and 16 per cent for the government’s campaign against corruption.

At the Sona, Duterte did not curse. He delivered a well-trimmed speech. He didn’t roll up his sleeves either. The president did not brag of his achievements. He has signed a total of 134 laws and joint resolutions in his first two years. Eight of his 28 priority bills were passed, paving the way for free tuition up to college in state universities, free irrigation and a return programme for Filipino scientists. He exceeded the number of bills signed by his immediate predecessor, a sign of hard work and support from Congress.

In a prediction, Bobby Tuazon, director of Policy Studies at the Centre for People Empowerment in Governance (CenPEG), said: “President Duterte will not mellow as far as his all-out drugs war is concerned — it is his main agenda.”

This hardline approach could be his political Achilles heel. Duterte faces complex problems such as the people’s acceptance of the proposed basic law for Filipino-Muslims in the south, and a nationwide shift to federalism.

Pulse Asia’s June survey said 56 per cent of Filipinos want more jobs, 52 per cent prefer controlled inflation while 48 per cent need higher salaries.

Members of Duterte’s elite political base also have conflicting agendas as far as a shift to federalism is concerned. His base will begin to crack and threaten his own populist appeal. Seeing the cracks, the political opposition led by the Liberal Party of former president Benigno ‘Pinoy’ Aquino, and several groups are forming a united front against Duterte.

They are against Duterte’s campaign on illegal drugs, a less popular issue, and tax reform, a very popular issue because it has been blamed for the rising prices of commodities. Duterte said he will not end tax reform.

Meanwhile, the opposition’s search for a unifying leader has been limited. Vice-President Leni Robredo of LP has been lukewarm to leadership since she won in May 2016. Senator Leila de Lima was imprisoned in 2016 for having allegedly allowed drug lords to continue operating when she was justice secretary from 2010 to 2016. Former Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno was ousted in May 2017.

Duterte’s political battle is on the rise, as opposition leaders rise up against him. In response, he has proposed to step down as soon as the people ratify the proposed charter change.

Many believe the sacrificial gambit (for charter change) is calibrated not to lessen the value of a shortened presidency. His term is supposed to end in 2022.