China’s Silk Road ambition

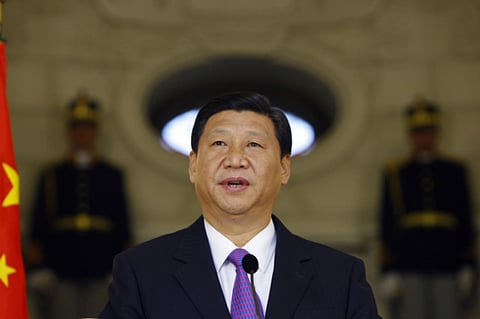

Xi undoubtedly has a domestic motive behind seeking a revival of Silk Road

The phrase “Silk Road” evokes a romantic image — half history, half myth — of tented camel caravans winding their way across the trackless deserts and mountains of Central Asia. However, the Silk Road is not just part of a fabled past; it is an important feature of China’s current foreign policy. The historical Silk Road comprised an overland and a maritime route, both of which facilitated the transfer to Europe of South and East Asian goods and ideas, from Chinese tea to inventions like paper, gunpowder and the compass, as well as cultural products like Buddhist scripture and Indian music. Likewise, the Silk Road — primarily the overland route, which also passed through the Arab world to Europe — gave China access to Indian astronomy, plants and herbal medicines, while introducing it to the Buddhist and Islamic faiths.

Thanks to Chinese admiral Zheng He, who steered his naval fleet across the Indian Ocean seven times in the early 15th century, the Chinese wok became the favourite cooking vessel of women in the southwestern Indian state of Kerala. Chinese fishing nets still dot the waters off Kochi. In 1411, Zheng erected a stone tablet — translated into Chinese, Persian and Tamil — near the Sri Lankan coastal town of Galle, with an inscription appealing to the Hindu deities to bless his efforts to build a peaceful world based on trade and commerce. Six hundred years later, Chinese President Xi Jinping is espousing a similar goal — only he is appealing to political leaders throughout Europe and Asia to advance his cause.

In September last year, in a speech at Kazakhstan’s Nazarbayev University, Xi announced the so-called “Silk Road Economic Belt”, a new foreign-policy initiative aimed at boosting international cooperation and joint development throughout Eurasia. To guide the effort, Xi identified five specific goals: Strengthening economic collaboration, improving road connectivity, promoting trade and investment, facilitating currency conversion and bolstering people-to-people exchanges.

The following month, the other shoe dropped. Xi, addressing Indonesia’s parliament, called for the re-establishment of the old sea networks to create a 21st-century “maritime Silk Road” to foster international connectivity, scientific and environmental research and fishery activities. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang subsequently reiterated that goal at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit and again at the East Asia Summit last year. Since then, the establishment of a modern overland and maritime Silk Road has become official Chinese policy, endorsed by the Communist Party and the National People’s Congress.

Xi has emphasised that the goal of the Silk Road economic initiative is to revive ancient ties of friendship in the contemporary globalised world. But he undoubtedly has a domestic motive as well, rooted in the growing prosperity gap between eastern and western China. The concentration of economic activity in the cities and special economic zones of the east has generated energy-supply and environmental constraints and bottlenecks that are hampering China’s ability to achieve the sustainable, inclusive growth that it needs to attain high-income status. The government hopes that the Silk Road initiative will make China’s west and southwest regions the engines of the next phase of the country’s development.

Nonetheless, the initiative’s international dimension remains the most relevant — and complex. Chinese diplomats have pointed to a constellation of mechanisms and platforms built or strengthened in recent years that could help maximise its impact. These include the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation; the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Corridor; the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor; the Chinese-built Yuxinou Railway from Chongqing to Germany (and onward to north European ports); and the new and incipient energy corridors between China and Central Asia, as well as Myanmar.

Moreover, China has established the New Development Bank with its fellow Brics members (Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa) and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank — institutions that will undoubtedly benefit from China’s enormous investable surplus. Given China’s prominent role in both, they could easily be used to provide financing for Silk Road-related programmes. But, though China may not struggle to finance its Silk Road ambitions, it is likely to face political resistance — especially with regard to the maritime route. At a time when China’s assertive stance in the South and East China Seas is provoking anxiety among its neighbours — including Japan, Vietnam, the Philippines and Singapore — the Silk Road initiative has aroused significant geopolitical apprehension. In fact, these fears have a strong historical basis. Zheng’s expeditions involved the use of military force in present-day Indonesia, Malaysia, Sri Lanka and India to install friendly rulers and control strategic chokepoints across the Indian Ocean. He intervened in the dynastic politics of Sri Lanka and Indonesia, abducting and executing local rulers. He even seized the relic of the tooth of Buddha, a symbol of Sri Lankan political sovereignty.

The countries along Zheng’s route therefore recall his adventures not just as initiatives to promote trade and establish commercial links, but also as direct military intervention in their affairs, under the pretext of ushering in a harmonious world order under China’s emperor. Reminding them of this painful past may not be entirely in China’s interest. This is not to say that the modern Silk Road would benefit only China. On the contrary, its overland and maritime routes could attract considerable investment to participating countries — especially from China, as it seeks new avenues for deploying its vast reserves. But the modern Silk Road’s establishment will also mark a step towards reinvigorating the ancient Chinese concept of tianxia, in which the Chinese emperor was considered the divinely appointed ruler of the entire known world.

Many Asians still remember Japanese efforts before and during Second World War to create a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” — a self-sufficient bloc of countries, under Japan’s leadership — through conquest. Might China be on a similar — albeit less openly aggressive — path?

— Project Syndicate, 2014

Shashi Tharoor, a former UN under-secretary general and former Indian minister of state for Human Resource Development and minister of state for External Affairs, is currently an MP for the Indian National Congress and chairman of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on External Affairs.