Arab concerns over Iran not a war cry

There is no appetite for the chaos caused by an Israeli or western attack against the country, despite fears over its expansionism

The image of Iran in the Arab public mind has changed in the last three decades. Its popularity has declined on the Arab street; albeit for reasons that are nothing to do with the concerns of Israel and western powers. It would be a mistake to depict the widespread Arab concerns over Iran as an act of support for an Israeli or American war against it.

When the Islamic revolution began in 1979 under the leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini, it aroused considerable admiration in the Arab street. It presented a model of organised popular action that deposed one of the region's most tyrannical regimes. The people of the region discerned in this revolution new hope for freedom and change.

The Arab street embraced the revolution without any particular unease about its sectarian or ethnic dimensions. The majority of Arabs are Sunnis and the majority of Iranians are Shiite. Although the Shiite dimension was present in the revolution from the very first day, the majority of Arabs did not worry.

Indeed, when the war between Iraq and Iran began in 1980, a significant segment of the Arab street continued in its positive outlook towards Iran.

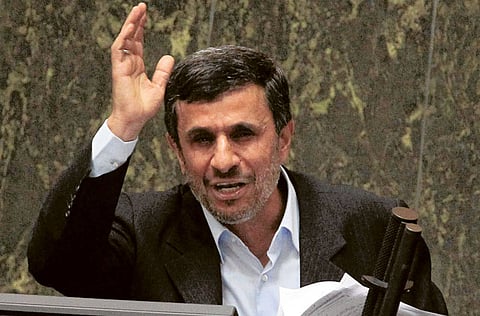

Iran's popularity grew markedly because of its support for the Lebanese and Palestinian resistance at a time when many Arabs felt their own regimes had abdicated their duties towards Palestine. In fact, during the 2006 Israeli war in Lebanon, the two most popular figures in Sunni Cairo were Iran's President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Hezbollah's leader, Hassan Nasrallah.

Turning point

Relations between Iran and Arab public opinion took a decisive turn with the bloody events that engulfed Iraq in 2005. Arabs were horrified by the widespread sectarian violence. Some accused Iran of igniting the situation further by training and arming the Shiite militias, who were reported to have committed serious atrocities against the Sunnis in Iraq.

These events triggered a wave of anger at Iran in most parts of the Arab world. It even spread to the north African countries, which had never had any sectarian interaction with the Islamic Republic.

Subsequently, Iran moved to support the regime of Syrian President Bashar Al Assad. The Arab street saw in this further evidence of Iran's sectarian trajectory, worsening its negative image in the minds of most Arabs.

An opinion poll conducted by James Zogby on behalf of the Arab-American Institute Foundation in July 2011 found there was a "shocking" drop in Iran's popularity in the six countries where the poll was conducted, with the exception of Lebanon. The main factor for this decline was the role played by Iran in the region.

Yet, it is necessary to distinguish between the reasons for the Arab position towards Iran and the Israeli and western view. Arabs are uneasy over Iran's expansionist policies and its sectarian nature. However, they do not view the Iranian nuclear programme as a threat.

A poll conducted by Shibley Telhami of the University of Maryland in October 2011 showed that more than 64 per cent of those surveyed believed it is Iran's right to continue its nuclear programme. It is not possible to understand this Arab stand without noting their view of Israel's nuclear arsenal. Arabs are evidently more worried about Israel's nuclear arsenal.

Nuclear arms race

Their logic is clear: as long as Israel possesses nuclear weapons, it is the right of the region's countries to also try to acquire them. Therefore, in order to prevent the escalation of a nuclear arms race, it is essential that the entire Middle East becomes a nuclear-free zone.

The Arabs recognise that Iran is a neighbouring country. It always was, and will remain a pivotal player in the political, economic and cultural fabric of the region. In this regard, Israel's threat to launch an attack on Iran does not have support on the Arab street for several reasons.

Most importantly, a war with Iran carries a number of risks whose consequences would be unpredictable both in the near and distant future. The neighbouring Arab Gulf states would find themselves with a grave security reality, which could lead to a dangerous future. Thus, the Arabs hope to balance their relations with their neighbour, Iran, in a peaceful manner that neutralises its expansionist ambitions and halts its interference in their internal affairs.

This possibility is enhanced by the Arab revolutions that will potentially correct the regional balance of power. The Arab spring has inspired the region's people with a vision of change. Yet, there is a long road ahead before they attain political and economic stability. A war with Iran would distract attention from the needs of the democratic transition to focus on demands of war. While it is easy to predict its beginning, it is almost impossible to presage its end.

War would redraw alliances and elicit external intervention into the affairs of states and groups. In the event, the Arab spring would end and be replaced by a Middle East autumn, one which would not give the region and the world anything but misery and danger.

— Guardian News & Media Ltd

Wadah Khanfar is a former director-general of Al Jazeera television network.