Grace Jones was sitting in an opulent hotel suite in Paris, naked underneath a fur coat, opining about her act. “The performer, out there, takes a risk,” she said, sipping Champagne. “It’s a lonely place. But it’s a fascinating, lonely place.”

That’s a signature moment from Grace Jones: Bloodlight and Bami, a documentary that traces nearly five years in the life of the singular vocalist, unparalleled stage goddess, fashion renegade and general paragon of the fabulous life, who will be 70 in May.

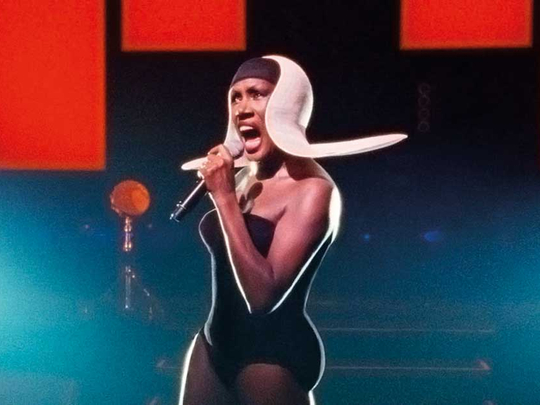

This is also Grace Jones: “I look like a bug from outer space.” At that particular moment she was wearing a black headpiece that covered her eyes and extended behind her like an exoskeleton. Alongside her gift for one-liners, Jones’ extraordinary collection of chapeaux — “I have a nice hat head,” she said demurely in a phone interview last month — is on display in the film, which opens April 13.

Directed by Sophie Fiennes, it tracks Jones starting in 2005 as she records an album, gigs around the world and, most revealingly, visits family in her native Jamaica, where she and her clan discuss their strictly religious upbringing and the violence of her stepgrandfather, known as Mas P. (Bloodlight is Jamaican musician slang for the red light of a recording studio, and bami is a local flatbread.) Even on modest family outings, she rocks notable headgear.

“The stage Grace, it’s not a facade, it’s not a fake — it’s a manifestation,” said Fiennes, a British filmmaker and sister of actors Ralph and Joseph, who has also made films about Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek and painter Anselm Kiefer.

“Grace is always living the limitless possibilities of being — the possibilities of every moment, that you could live it more extremely,” Fiennes said, adding, “I always remember when she saw the film, she stood up and said, ‘I love the smell of your film.’” Jones also taught her how to hula-hoop.

Since the cameras stopped rolling, her career has had a reboot: she’s headlined major festivals like Afropunk in Brooklyn, released a best-selling memoir and seen her iconic styles revived. She’s even name-dropped in Black Panther, whose Dora Milaje fighters have a bit of her aesthetic. “People always said I’m ahead of my time, but how far ahead of my time? Am I just arriving right now?” she said, laughing. “I don’t want to sound like a crazy ex-acid tripper,” but “it does all seem to come together in a very cosmic way.”

Speaking one night from her brother’s home in Los Angeles — Jones is nocturnal, or as she put it, “I’m a vampire, so get over it” — she discussed her newfound willingness to show a softer side of herself. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

You’re used to being on camera, but was it different to have documentarians follow you for years?

Once I decided I trusted Sophie, I just pretended she wasn’t there. When you grow up in the modelling world, you get to a point where you are all the time having your guard up about how you look. There was maybe one time, I thought, oh, Sophie dear, I look a little bit fat there — [laughs] not like in my pictures. And I just say to myself, what am I doing? This is not about that. It’s OK to be myself.

Your stage presence is so fierce, what did it feel like to show yourself in more vulnerable, intimate moments, like meeting your newborn granddaughter?

Normally I don’t like people to see that vulnerable side of me, it’s not a side that I normally would share with the world. But when I decided to do the film, I felt strong enough, actually, to show the vulnerable side. A lot of my stage performance [persona], I found out later, was actually coming from Mas P, who was my bully, who was an abuser. And I always thought maybe that is why that stronger side was there, to protect the little girl in me. I like to call the little girl Bev [her middle name, which she went by as a child, is Beverly], and Grace is the protector. [Laughs] I’m starting to sound like Sybil.

In the film, we see how often you still have to keep people in line about how to respect your vision.

There’s a lot of fantasy connected to me, I know that. I had to be very strict on managers, because sometimes they do have other agendas. I literally managed myself for 15 years. I learned a lot from working with Chris Blackwell [the Island Records founder, who released her debut studio album, Portfolio, in 1977]. I still call him one of my mentors. I believe he tested me on some things — when we were recording sometimes, and he wouldn’t show up, just to see if I was going to handle everything right.

And when things would go wrong, I would walk out of the studio. I’ve done a lot worse than what you’ve seen in the film. If I don’t want something, people will tell you, there’s nothing you can do — you couldn’t pay me enough, you can’t buy me to do something I don’t like, and that’s just how I am. I don’t know if it’s from growing up in a very, very strict family. It could be that — after I got out of there, and I had my own say, that I’m going to stick with how I am feeling.

You’re also always fighting to get the right contract. How did you build that expertise?

I just would not have lawyers ever have any meetings without me being there. They always say, ‘Oh, just go, do your tour, do your thing, look pretty, go on TV, let us worry about that.’ I didn’t do that. I would come to every meeting with the contract, and if I didn’t understand, I’d have them explain it to me. I’d come with a sandwich, and sit among all the guys. I’ve had new artists see me on a flight and come up to me with a contract and say, can you read this for me?

You lament the dwindling of night life culture: ‘11:30 in New York, and people are leaving a party. Honey, they must be depressed.’ Is it hard to find people who can keep up with you?

Oh definitely. Nowadays, even the younger ones — I’m going, oh my God, come on, what’s wrong with you guys? It wasn’t just keeping up with me — in the ‘80s, all of us would just seem to have more energy. I used to love giving parties in my apartment in New York, it was a loft apartment, where I mean... people were crashing the parties and it would be some famous movie star. They would sleep in the bathtub, or anywhere. You’d wake up and there’d be bodies everywhere.

Do you ever feel old?

Never. I feel wiser.

In your book you mention that you’re not a fan of a lot of pop artists, like Miley Cyrus and Nicki Minaj. Who do you like to listen to now?

I love the Jamaican reggae artists that nobody really hears of over here, I think the only one that has broken through is Chronixx. I loved Amy Winehouse, I thought she was very unique. Sam Smith. I heard lately a girl, she has that kind of French name and she’s kind of looking like a mini-me — she was wearing the hair kind of like me, a suit.

Janelle Monae. Her new single sounds Janet Jackson-y.

Oh no. Well, there goes that. You see, this is the problem, when you can’t tell who’s who anymore. It just seems like everyone’s on the same merry-go-round technically, every voice has something put to it, so that everybody sounds the same. It sounds mechanical, there is no warmth. I refuse to let them put stuff on my voice, absolutely not.

Did you learn anything about yourself from watching the film?

I’m funny! I found myself laughing at myself more than I normally would, going, oh my God I can’t believe I did that, did I really say that? Because it’s not scripted, it’s not like I have to rehearse any lines — things would sometimes come out of my mouth and I’d go, oh Jesus.