When Nujoom Al Ghanem speaks, her gaze gently cascades over you, eventually gliding away into the distance as a reel of memories unspool in her mind’s eye and plays out in front of mine.

It only takes five minutes to understand why this award-winning Emirati filmmaker, primarily a documentarist, is an innovator of Emirati cinema — she’s a gifted storyteller.

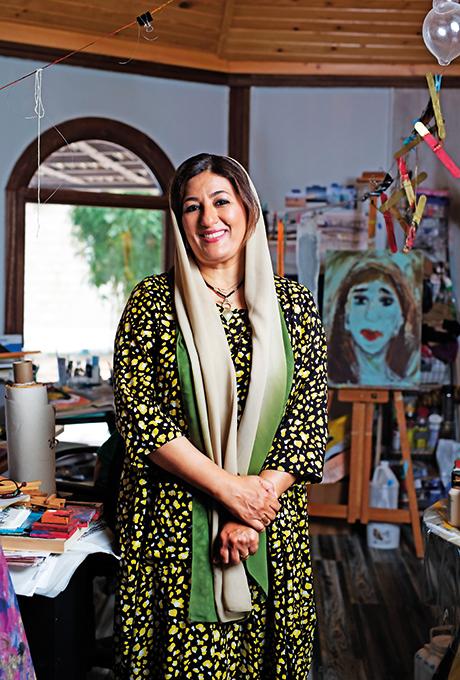

I haven’t been to Nujoom’s maternal grandparents’ two-storey house by the Dubai Creek where she grew up in the sixties. But sat in her present-day studio overlooking the pool at her Al Wasl home, only guided by her words, I can envisage scenes of teenage Nujoom lounging in the terrace, watching the merchant ships sail by, journalling their passage amidst other wistful entries of ‘daily feelings about my grandmother punishing me and other such things,’ she laughs, resuming eye contact. ‘Some people look at the eyes when they talk, others watch how the mouth moves. We memorise people through what they say and even if we forget the expression, the words remain with us.’

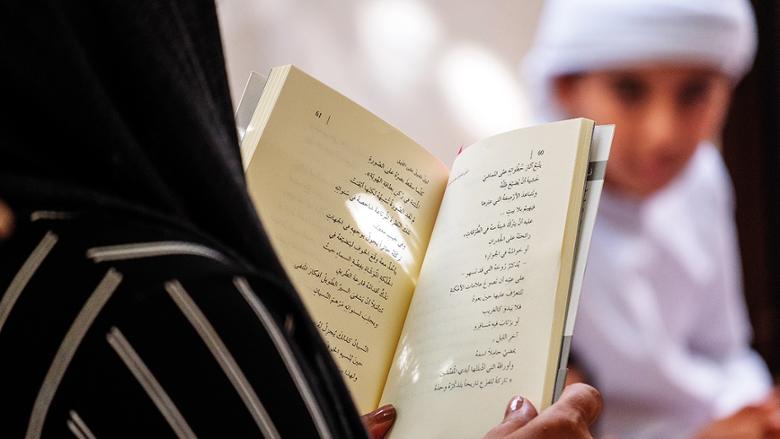

Being one of the UAE’s leading contemporary poets — one who championed the free-verse movement of the eighties — means Nujoom, 56, knows the indelible impression of words. It’s apparent in how feted her eight poetry collections are in the Arab literary world, her consistent appearances at the Emirates Airline festival of Literature and her position as a board member of the International Prize for Arabic Fiction. However, her reverence for words manifests the most in her speech — measured, never slapdash and always panning for anecdotal gold.

Words, she reveals pointing at the paintings of faces that cover the walls of her studio from ceiling to floor, also form the framework of her art. ‘[That’s why] their mouths are suggestively painted and are the outstanding features in every portrait,’ she says about the stark portraits of women in rough brushstrokes, which are part of a series she’s been plugging away at for years.

Filmmaker, poet, artist — Nujoom is a veritable triple threat. Like the free verse she holds dear, her creativity is fluid and takes the shape of whatever artistic medium best communicates her vision. This versatility is the driving force that made her the first female artist to have a solo exhibition at the UAE’s National Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennale — the exhibition considered as the art world’s Olympics. Nujoom was hand-picked by curators Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath to be the UAE’s artistic torch bearer this year with a multidisciplinary video installation called Passage that combines poetry, film and art (her portrait series is a part of it) to unpack the loaded theme of displacement. Topical and culturally on the ball, considering we live in a time when the world is grappling with a refugee crisis of unprecedented magnitude — a record 70.8 million people have been displaced from their homes by the end of 2018, according to a United Nations report.

In the vein of the split screen video in Passage — one is the surrealistic fictional tale of displaced woman Falak and the other behind-the-scenes footage of Nujoom and Syrian actress Amal Hawijeh creating the installation — tells two sides of a story. The chosen theme is both a commentary on the Arab World’s enduring grievance and a personal tale of both Syrian national Amal’s and Nujoom’s quest for home.

But what could Nujoom, a citizen of the secure and protected UAE, know of displacement and the struggle to fit into a new society, the emotional instability that comes from not knowing where you belong geographically?

Plenty, it appears, as she charts out the passage of her life: ‘I wasn’t sure why, but I was raised in my maternal grandparent’s house separate from my siblings,’ Nujoom explains, going on to describe her struggles at school, especially how she felt ‘out of place and suffocated in the dorms of the UAE University,’ which made her drop out and resume her job as a journalist at Al Ittihad newspaper. ‘Then, when I travelled to the US and Australia (where she completed her bachelor’s in Video Production at Ohio University and MA in Film Production at Brisbane’s Griffith University in 1999), I had to fit into a new society and community where I was just a nameless person; your own history and practice means nothing to anyone and that leaves a hole inside you,’ she says, her voice cracking.

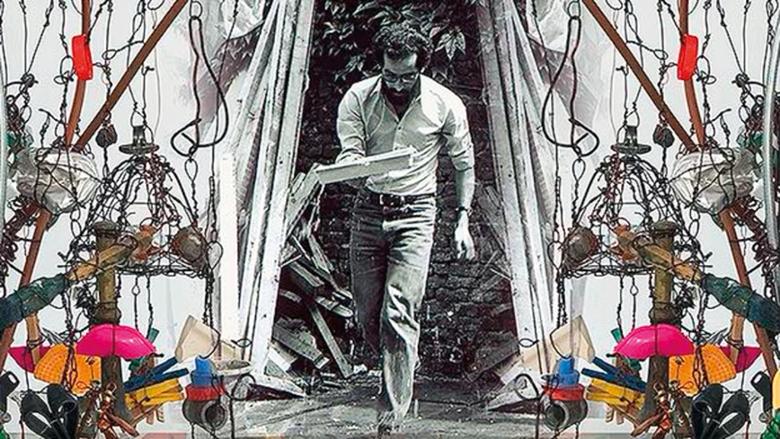

[No filter: Jalal Bin Thaneya on the raw power of industrial photography]

It wasn’t until years later, after two degrees, three children and a visit to a kinesiologist due to ill health that Nujoom came face to face with the full extent of her displacement. ‘She [the kinesiologist] asked me why the word ‘territory’ is in my system and consciousness.’ I had kept repeating the phrase ‘this is not my territory’ unconsciously until it became a part of who I was and I was messed up — the only place that felt like home was the room I slept in. It’s a scary realisation to have as an adult and a mother. And it is an unfair feeling for any soul.’

In a world that Nujoom describes as ‘being in a question’, this universality of the feeling of displacement, one that transcends nationality, gender, religion and ethnicity, is the connection between the UAE and the piece in the UAE pavilion, and entreats sceptics to look beyond their myopic worldview of politics.

Film, she feels, is instrumental to that change, a reason her hyperlocal documentaries that deal with UAE-specific stories — such as about the first female Emirati camel owner Fatima Alhameli in the 2014 docu-feature Nearby Sky (it won the best documentary award at the GCC Film Festival), and Sounds of the Sea about traditional sea songs and the Umm Al Quwain fishing community that is trying to preserve them – have found appreciation internationally too.

‘I think films are bridges between cultures. When my films are screened at international festivals I can see people relate to the questions, characters and experiences in my film,’ she says with a humble smile.

Mind you, these are all films made in Arabic with only English subtitles. It’s a conscious choice Nujoom made early on as a student in the US, when her acting teacher made her a case study in the class and revealed language’s ability to tear down walls. ‘My professor one day insisted that I perform in Arabic and not English, showing the difference in the [authenticity] of the emotions. When you speak your mother tongue, you don’t create barriers. In performances, when you’re in a sensitive emotional state, language is a cane you can lean on and stay grounded in. Language holds your culture, your memory, your identity. It is your inheritance.’

Rich childhood

In Nujoom’s case, her inheritance is also an artistically rich childhood that moulded her into a multidisciplinary future self. Books replaced toys and artistic, culturally clued-in aunts, especially the youngest, Fatima (‘almost like my real mother’), substituted age-appropriate company and fused art and writing into her DNA. ‘I started reading out of boredom, books were my entertainment and brought other worlds to me when I wasn’t allowed to go out.’

She was exposed to the wonders of the lens early on too. ‘My aunts would take us to the cinema and they had a camera at home, so I’d constantly pose for them’. Soon, young Nujoom found herself ‘accumulating fantasies and fiction in the back of [my] head,’ which eventually saw her write and stumble into an internship at Al Fajr newspaper. What ensued was a nine-year-long journalism career that saw her progress from a trainee at Al Fajr to reach Al Ittihad newspaper’s head of cultural department in Dubai and Northern Emirates. In Nujoom’s own words, the freedom of ‘having my own car and escaping home to go to work’ came with a financial glass ceiling: ‘I couldn’t move forward without a degree. My salary was that of a high-school graduate.’

It spurred her on to take a leave of absence from work and pursue video production abroad. ‘I was tired of journalism but it was mandatory to use my leave for a media-related course.’ Encouraged by her husband – Emirati poet Khalid Al Budoor – who recognised her ambitions, Nujoom flew the coop to Ohio, where she discovered a passion for film, a medium that synthesised the best aspects of all the art forms she’d been raised to love. ‘I loved that film requires you to have knowledge of different areas. It’s a sophisticated medium that [borrows] from writing, painting, photography, music etc.’

Does that extend to poetry too?

Nujoom is emphatic in her response: ‘Of course! Poetry is also an art of imagery. You can’t write good poetry if you can’t use your words to compose images. I read poetry to myself before the shoot or to the characters to energise and enrich them – Amal’s most astonishing performance in Passage was after reading poetry to her.

‘Even if I don’t try, I think poetry [creeps into my cinematography],’ she shrugs. ‘It’s how I’m programmed.’

With her Biennale installation, the inclusion of poetry is an attempt to push the envelope and establish the symbiotic relationship between art forms. Nujoom’s rendition of her 2009 poem The Passerby Collects the Moonlight forms the soundtrack to the 26-minute film. ‘It is a moving ‘eulogy to all lost souls’ and, specifically, the suffering of two of her friends whose lives were rend by displacement. ‘One was very ill and lived in exile all his youth. The other never got the chance to become a citizen and he lost one of his legs.’ Nujoom’s voice trails off into silence and her gaze to the light bouncing off the pool outside as she tries to collect her composure. Curators Sam and Till, she later tells me, broke down and cried when she read the poem out to them during one of their Botim brainstorming sessions in the run-up to creating Passage.

[Award-winning Emirati spoken word poet Afra Atiq: into her spellbinding universe of verse]

She draws on her earlier point about the power of language. ‘I describe [my friends] as strangers in Arabic, but the word for strangers in Arabic is different from English and translates to alienated.’

On the personal front, Nujoom no longer feels alienated. Over the years, she’s trained herself to shed her loneliness and feel at home in her family, her country and her industry. Her daughter Fatima (also an artist) keeps her company in the studio during our interview; her husband has always been her creative collaborator, helping her with research and scriptwriting in her films, and while she’s humble, she doesn’t hide her light under a bushel. ‘The curators chose me to represent the UAE with a site-specific installation because they know I can present something different.’

This sureness has come to her with time – an element whose gravity she values in her personal story and the stories she records as a documentarist. ‘I believe we need time to get to know people and win their trust.

‘You have to give yourself time to live with them, eat with them, spend quality time with them as a human,’ she says, going on to explain how she and husband Khalid spent three years just going back and forth to get to know the fishing community filmed in Sounds of The Sea.

‘They need hours, to sit in front of your camera and forget about it,’ she adds, glancing at the camera that’s been zoomed in on her all day during the interview before confessing in embarrassed laughter that ‘I prefer being on the other side of the lens.’

Eventually, Nujoom too forgets about the camera and is engrossed discussing poets and filmmakers who inspire and shape her vision – ‘Mahmoud Darwish, Ezra Pound, Rimbaud and Aragon, Basho are all poets I keep going back to. Their work is always new and available with every reading.

‘I have a special appreciation for Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman.’ After a period of silent internal battle, she throws in the towel and adds Steven Spielberg to the list.

It’s not that she’s averse to commercial cinema, and whole-heartedly endorses the merits of genres like sci-fi and comedy, but she feels Hollywood and Bollywood’s pervasive presence blinds UAE moviegoers to the possibilities of cinema as serious art as one would see in cinematic traditions of Eastern Europe or France; or the cultural pedestal poetry has been placed on in the UAE. A groundswell of venues and initiatives such as Cinema Akil, Abu Dhabi’s The Space and Sharjah Art Foundation provide opportunity and access to state-of-the-art technology, but Nujoom bemoans a dearth of ‘profound stories and anecdotes that will stay with us after we leave the theatre. We have so many such interesting stories in the UAE to be discovered and portrayed and presented to the world.’

It’s these stories Nujoom tries to unearth with each documentary, from 2017’s Sharp Tools that documented the late contemporary Emirati artist Hassan Sharif, to 2011’s Amal, that charted Amal Hawijeh’s life as the voice behind beloved cartoon character Captain Majed.

Meanwhile, she continues to cast a long shadow on the UAE’s cinematic and artistic heritage while also being a leading light, embodying the duality that runs through Passage.

The visionary’s vision of the legacy she’d like to leave behind is simple: ‘I just want people to enjoy my work. To relate to it.’