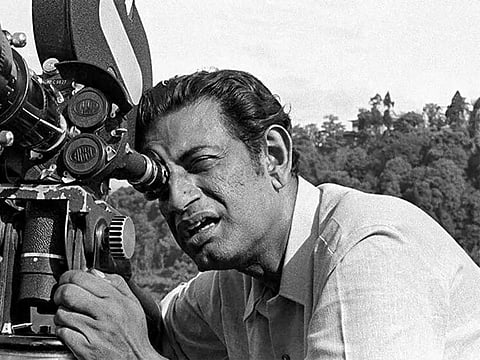

Happy 100th birthday, Mr Satyajit Ray!

The centenary year of the maestro of Indian cinema gets off to a quiet start today

Dubai: The doors of the airy top floor flat at Bishop Lefroy Road is unlikely to be kept ajar – like every year on May 2 – for people to still come in just for a visit or a floral tribute in front of his photo frame. This had been the practice at the Ray household since Satyajit Ray, the ultimate maestro of Indian cinema passed away nearly 30 years ago, but it’s’different this year.

The world has changed…and it’s in a state of paranoia now. As Indian cinema is mourning the loss of two of it’s favourite sons in Irrfan Khan and Rishi Kapoor, the never-ending lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic would deter the cinephiles of Kolkata to visit their annual pilgrimage on what would have been Ray’s 100th birthday.

The thought of Ray completing a century already may sound a little incredulous – and suddenly makes him all that more remote an icon like say, Rabindranath Tagore, the Nobel laureate bard whose birthday is celebrated as a social event around the state of West Bengal. Ray, who was a Brahmo (a Hindu reformist faith introduced by Maharshi Debendra Nath Tagore, the iconic poet’s father) and a quintessential Renaissance man, was never really known to like the fuss about his birthdays – while he often used to check in at a central Kolkata hotel to work in solitude on his upcoming film scripts.

It was almost a privilege to grow up in Kolkata in the mid-Eighties – as it was unanimously hailed then as the cerebral film capital of India. Bollywood was always the hub of Indian cinema and shaped it’s history, but the City of Joy boasted of the holy trinity of Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak – who pursued their excellence in realistic films from the usually derelict studios and with shoestring budgets.

It’s not for nothing that ‘Manik da,’ as he was popular as in the Indian film industry, is hailed as the director of directors in the Indian film ministry even after 30 years of his death. His versatility in various creative aspects of filmmaking – right from writing own screenplays, music direction, design of costumes and posters are part of folklore – not to speak of the fact that his work in children’s literature enjoy the bestsellers’ tag even to this day.

Just how big was Ray as a filmmaker? The idolatory that he enjoyed in India – not to speak of the status of the ruling deity in his own state – may make the new age student of cinema lose the perspective somewhat. The best he or she can do to is to go back to the work of this Lifetime Achievement awardee from the Academy and soak in the underlying humanism in it. I would like to fall back on the words of Akira Kurosawa, another Oriental master from Japan, whose fascination after watching a restored version of ‘Pather Panchali’ (the first part of the Apu trilogy, followed by Aparajito and Apur Sansar) encapsulates the Ray idiom very objectively in the following words.

‘’The quiet but deep observation, understanding and love of the human race, which are characteristic of all his films, have impressed me greatly. … I feel that he is a “giant” of the movie industry. Not to have seen the cinema of Ray means existing in the world without seeing the sun or the moon,’’ said the creator of masterpieces like Throne of Blood and Rashomon.

‘’ I can never forget the excitement in my mind after seeing it (Pather Panchali). It is the kind of cinema that flows with the serenity and nobility of a big river. People are born, live out their lives, and then accept their deaths. Without the least effort and without any sudden jerks, Ray paints his picture, but its effect on the audience is to stir up deep passions. How does he achieve this? There is nothing irrelevant or haphazard in his cinematographic technique. In that lies the secret of its excellence,’’ said Kurosawa.

My first encounter with the giant of a person was way back in the mid-Eighties when as a First Year student of English literature in Jadavpur University, one of our professors had a surprise gift as our freshers’ welcome. It was invitation for a memorial lecture named after one of Ray’s professors of his Presidency College days where Ray walked in sharp on time – accompanied by his wife Bijoya Ray.

As a gaggle of star-struck first year students stopped him for the autograph, a gracious Ray obliged most of us, just muttering in his baritone once under his breath: ‘’I will get late.’’ A one hour lecture which followed was a masterclass in many ways – flawless diction, command over English and economy in expression – laced with a subtle sense of humour.

The exact words have faded from memory, but I remember his observation about how he feels most comfortable practising his craft in the rickety studios of Kolkata with it’s share of problems – but he couldn’t think of working anywhere else. The only Hindi feature film in his all-too-familiar bibliography – Shatranj Ke Khiladi in 1977 – was a period film and shot mostly in Lucknow and in the studio sets of Kolkata.

My next meeting, another chance one, came a few years later and what we could call a one-to-one now. I had just begun dabbling in freelancing in Kolkata for The Telegraph, one of it’s leading English dailies - and it was an interview to work on a feature to develop on a lecture that he had given somewhere – that films should be made part of regular academic curriculum. Managing to get the phone number from the newspaper office (a landline which he always picked himself), I dialled it from home with much trepidation – once again the baritone at the other end of the phone was unmistakeable.

An appointment was fixed and I landed up – my stomach in knots - to meet the great man. Ray was seated on his famous easychair and gave his dispassionate views on the subject, drawing examples on how film studies had already become an integral part of options in European and American universities.

The only place for film studies in India those days was the film institute in Pune and it was much, much later that the first film institute in eastern India – suitably named after him - would be set up in Kolkata many years back.

It was the only time that I had stepped into that house, as my specialisation of work turned out to be a far removed one as I moved on in life. The sense of awe (or fanboy moment, if you like) has, however, stayed with me almost a lifetime after the incident.

Happy 100th birthday, Mr Ray!

The Ray Filmography

Pather Panchali (Song of the Road) 1955

Aparajito (The Unvanquished) 1956

Paras Pathar (The Philosopher’s Stone) 1958

Jalshaghar (The Music Room) 1958

Apur Sansar (The World of Apu) 1959

Devi (The Goddess) 1960

Teen Kanya (Three Daughters) 1961

Kanchenjungha 1962

Abhijan (The Expedition) 1962

Mahanagar (The Big City) 1963

Charulata (The Lonely Wife) 1964

Kapurush-O-Mahapurush (The Coward and the Holy Man) 1965

Nayak (The Hero) 1966

Chiriakhana (The Zoo) 1967

Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne (The Adventures of Goopy and Bagha) 1968

Aranyer Dinratri (Days and Nights in the Forest) 1969

Pratidwandi (The Adversary) 1970

Seemabaddha (The Company Limited) 1971

Ashani Sanket (Distant Thunder) 1973

Sonar Kella (The Golden Fortress) 1974

Jana Aranya (The Middle Man) 1975

Shatranj Ke Khiladi (The Chess Players) 1977

Joy Baba Felunath (The Elephant God) 1978

Hirak Rajar Deshe (The Kingdom of Diamonds) 1980

Ghare Baire (The Home and the World) 1984

Ganashatru (An Enemy of the People) 1987

Shakha Prasakha (Branches of a Tree) 1990

Agantuk (The Stranger) 1991

Documentary

Rabindranath (1961)

Sikkim (1971)

The Inner Eye (1972)

Bala (1975)

Sukumar Roy (1987)

Short film

Two (1964)

Pikoo (1980)

Sadgati (Deliverance) 1981

Major awards won by Ray

1958: Padmashree, India

1965: Padmabhushan, India

1967: Magsaysay Award, Philippines

1971: Star of Yugoslavia

1973: Doctor of Letters, Delhi University

1974: D.Litt, Royal College of Arts, London

1976: Padma Vibhushan, India

1978: D.Litt, Oxford University, Special Award, Berlin Film Festival; Deshikottam, Visva Bharati University, India

1979: Special Award, Moscow Film Festival

1980: D.Litt, Burdwan University; D.Litt, Jadavpur University

1981: Doctorate, Benaras Hindu University, India; D.Litt, North Bengal University, India

1982: Hommage a’ Satyajit Ray, Cannes Film Festival; Viyasagar Award, Government of West Bengal

1983: Fellowship, British Film Institute

1985: D.Litt, Calcutta University; Dadasaheb Phalke Award, India; Soviet Land Nehru Award, Soviet Union

1986: Fellowship, Sangeet Natak Academy, India

1987: Legion d’ Honneur, France; D.Litt, Rabindra Bharati University, India

1992: Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement, USA

Akira Kurosawa Award for Lifetime Achievement Award, San Francisco International Film Festival

Bharat Ratna, India