Nowhere men

Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s characters wander the globe in search of meaning

The World Goes on

By Laszlo Krasznahorkai, New Directions, 311 pages, $28

All of us, according to the Hungarian writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai, possess just one fragile but fluid sentence. In a 2012 interview with The Guardian, several years before winning the Man Booker International Prize, he described human existence as a chance to “have some power to say something, for one sentence.”

That mortal urgency, to will as much meaning and power into a single sentence before it comes to an end, is manifest in every multipage, manic sentence in Krasznahorkai’s fiction. In the decades since his astonishing first novel, Satantango, in 1985, his sprawling sentences have established him as a cult figure among readers drawn to contrarian authors who sound like no one else. The Hungarian director Bela Tarr’s acclaimed adaptations of several of Krasznahorkai’s novels have also helped his growing visibility, particularly Tarr’s 1994 black-and-white magnum opus version of Satantango, more than seven hours long.

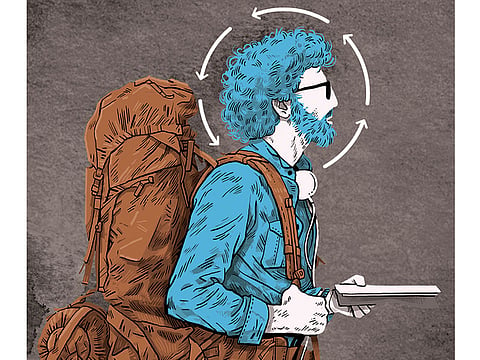

The World Goes On marks the seventh of Krasznahorkai’s books to appear in English with New Directions. The stories feature solitary men despairing in various locations. They despair in Kiev, Varanasi and Shanghai, “circling all around the globe like the second hand of a watch.” This drifting becomes the paradoxical oblivion of “wandering-standing,” a state the narrator of the opening story describes as the disquiet of listless, hunched-over men on every continent, men yearning to head somewhere — in any direction — yet going nowhere.

Krasznahorkai has engaged in quite a bit of wandering-standing himself. He first left his native Hungary in 1987 for a fellowship in West Berlin. After living in Germany, he wandered through rural Mongolia and China before travelling extensively in Japan. For a time in the 1990s he lived in Allen Ginsberg’s apartment in New York, drawn to the bleak forecast for humanity that the Beat poets were shouting in English.

This new collection of stories, like all of Krasznahorkai’s work, consists mostly of the searching, capacious sentences for which he has become known, each additional clause circling the unutterable like “a merry-go-round, around the thing itself,” as the narrator of Obstacle Theory states.

Krasznahorkai has dismissed the short sentence as “artificial”, a form that is no more than a custom of “the last few thousand years.” He is not immune, however, to the allure of a succinct end-stop declaration. Several stories in this collection, in fact, begin with them. One starts: “Memory is the art of forgetting.” Another story, Journey in a Place Without Blessings, is a series of brief numbered sections, many consisting of only a few haunting words, and some as short as “The congregation is silent.” Krasznahorkai executes these staccato sentences as skillfully as his signature expansive ones, and witnessing such a distinctive writer deviate a bit in sentence style is an unexpected pleasure of this new book.

As with any writer in translation, that pleasure wouldn’t be possible without Krasznahorkai’s excellent translators: John Batki, Ottilie Mulzet and George Szirtes. Batki is a self-proclaimed kilimologist, an expert in old weavings, which seems like a useful background for the intricate word-tethering of literary translation, and especially of sentences as elaborate as Krasznahorkai’s.

With impressive subtlety, the translations recreate the playful irony that undercuts the incessant anguish in each story, an anguish that can become predictable and therefore tiresome. In A Drop of Water, a man despairs about the towers of excrement among the ancient ghats and temples of Varanasi. But excessive fixation like this also heightens a reader’s attentiveness to the beauty of the next image, when the narrator’s attention shifts to a group of children, “swirling like a whirlpool around the hand holding the iPhone.” What an arresting contrast — the image of that most ubiquitous of devices causing a whirlpool of children in one of the oldest, continuously inhabited cities in the world.

The poignant juxtaposition of the ancient and the new is central to the story Bankers as well. A traveller arrives in Kiev to visit an old friend, hoping to join the catastrophe tourists headed to Chernobyl’s exclusion zone. To his surprise, his friend arrives at the airport with another man already in the car, a man who talks endlessly about workplace minutiae while the arriving traveller looks despondently out the window at the endless banks lining the streets of Kiev. Noticing everything from Megabank to Renesans Kapitol, the traveller, Fortinbras, who shares his name with the Norwegian foil to Hamlet, thinks to himself, “Good heavens ... what is going on here.”

For most writers, an impulse to capture the bewilderment of moving through a bank-ridden city might lead to a playful list of half a dozen bank names. But Krasznahorkai constantly pushes beyond the expected, escalating everything to the brink of deliriousness with an absurd list of 20 banks. To fully experience the exhilarating crescendo of a Krasznahorkai sentence requires a willingness to submit to this kind of frantic excess.

Not all the stories, however, are frantic and interior. Universal Theseus, one of the most haunting in the book, consists of formal lectures delivered in an ominous auditorium. At the outset of the first lecture, the speaker calmly tells his audience that he knows he’s been invited because someone else wasn’t available. He also admits what he does not know, which is who his listeners are or what they expect of him. He tells his audience he has a “lingering bad feeling” that they themselves “aren’t quite clear” what they want from him either.

After these delightfully brazen disclaimers, the lecturer decides to tell his listeners about the “deadly honey” of melancholy and what makes it “the most enigmatic of attractions.” When the lecturer observes a gentleman lock the door behind him, rendering him a prisoner in the auditorium, unable to escape his audience, it feels a bit like a self-fulfilling prophecy, as if he has willed himself into such an unbearable situation — and a subtle comment on the self-sabotage that humanity continually commits.

How to escape the bewilderments of the 21st century is the central question of the book: a “sequence of steps enabling one to back out of the world,” as the trapped lecturer puts it. Krasznahorkai’s stories refuse to submit to the expectation that fiction provide any kind of reassurance or intimation of redemption. What the stories offer instead is a singular kind of immersive intensity in scenes flooded with such despair that reading them feels at times like drowning in the spiritual questions of our era. When Fortinbras enters one of Kiev’s best-known landmarks, St Sophia’s Cathedral, he is surprised to find hardly any other tourists there. His friend explains that visitors rarely linger in Kiev now. They all rush right to the Zone to take apocalyptic photographs.

Wandering-standing in the cathedral, alone with the saints, the melancholy Fortinbras is aware of their gaze, inquiring of him what happened to the past. “Where is it,” he senses the saints asking, “where is that place where their soulful nature would mean something?” A chagrined Fortinbras, who had arrived in Kiev as eager to step through the emptiness of Chernobyl as all the other tourists, concludes that such a place may be nowhere.

–New York Times News Service

Idra Novey is the author of Ways to Disappear. Her second novel, Those Who Knew, will be published this autumn.)

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox