Ireland in crisis

With housing mortgages already in the red, the nation's banking system is on the verge of collapse, which risks pulling the fragile Eurozone into a second sharp crisis of confidence

The dark wooden panels and deep green leather benches stifle most sounds in the court, save for the attentive words in lilting English spoken by the High Court clerk. Standing at a polished table laden with foolscap legal briefs and beneath a golden gilded harp that dominates this Dublin court, there are 56 orders of repossession for property on the docket this September morning.

Most of the cases are adjourned in the hopes that bankers and borrowers will reach some form of settlement to prevent the homes from foreclosure.

But time is running out: Ireland's homeowners are in crisis.

According to the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) of Ireland, 40 per cent of the Republic's homeowners have negative equity in their homes as a result of a drastic drop in property values in the past two years.

And 36,000 are six months or more in arrears on their mortgage payments and on the road to foreclosure.

If that's not bad enough, the nation's banking system is on verge of collapse, at risk of pulling the fragile Eurozone into a second sharp crisis of confidence.

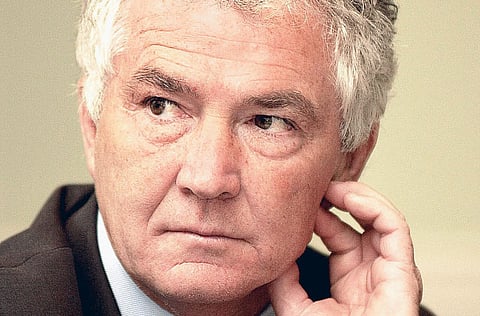

In that same Georgian granite court building on the northern side of Dublin's River Liffey, debonair ex-banker Sean FitzPatrick appeared to stand before a golden gilded harp and a judge in horsehair wig to be formally declared bankrupt.

The 62-year-old former chief executive and chairman of Anglo Irish Bank had a personal income of just 188 euros (Dh941.9) a week: He owes his former employers nearly 110 million euros in personal loans.

So far, the shaky coalition government of Prime Minister Brian Cowen has spent 30 billion euros keeping Anglo Irish bank afloat.

Yesterday, Finance Minister Brian Lenihan detailed that the overall cost of rescuing the nation's six banks will be 50 billion euros, a figure which has forced Irish authorities to suspend further bond auctions for two months at least.

On Wednesday, German government bonds rose as concern deepened over Dublin's ability to handle its public finances, its handling of bailouts for its banks and the fact that Cowen's coalition appeared to be crumbling. There is deep discord and growing anger at Ireland's sharp recession, growing unemployment, public service job losses, pay cut backs and an austerity programme that has cut hard and deep. This in a nation which three years ago was being touted as the Celtic Tiger.

With all of the uncertainly, the Irish government is forced to pay investors a record premium yield of 6.71 per cent for its 10-year bonds compared with the low-risk German bonds. Even then, the Irish bonds are a hard sell to nervous investors and institutions.

"Banking worries are at the forefront at the moment and the markets are very nervous ahead of the announcement by the Irish authorities," said Nick Stamenkovic, a strategist in Edinburgh at RIA Capital Markets Ltd, a broker from banks and money managers.

Sceptical

If bond traders are sceptical over Ireland's future liquidity, at least publicly, European Union officials are talking up Dublin's austerity policies.

EU Economics Commissioner Olli Rehn this week expressed confidence in Ireland's ability to continue to tackle its financial crisis, and he believes neither Ireland nor Greece will default on their sovereign debts.

"They have taken effective and determined action by means of financial repair, by means of fiscal consolidation and by means of structural reform," Rehn said in Tallinn at an event marking Estonia's entry into the Eurozone a year from now.

"More needs to be done but Greece is on track and Ireland is on track, so there will be no restructuring [of the euro]," he said. "I have full confidence in Ireland and its determination to compete the financial repair and the necessary restructuring of the banking and financial sector."

That financial repair is costly — so far Ireland's taxpayers are on the hook for 30 billion euros bailing out Anglo Irish Bank alone.

Just days before FitzPatrick appeared in court, he threw a lavish 62nd birthday party at his swanky seaside home in the shadow of the verdant Wicklow Mountains, catered by an events specialist company to ensure that all was right.

He also recently picked up second prize at his exclusive golf club's annual competition. As he stepped up to collect his award, someone shouted: "Where's our 30 billion?" That's a question most Irish want answered.

FitzPatrick's former employer has the distinctly dubious reputation of being the bank which the lost the most money anywhere in the world last year.

Indeed, it was two years ago this week, at the height of the credit crisis crunch, that the Cowen government decided to fully bailout all of the nation's six banks, whatever the cost.

That's a decision it may yet rue, given that the lifejacket has so far failed to inflate. Even after the full cost of 50 billion, it's uncertain what the state gets in return.

"The guarantee was supposed to have bought us time but two years later we're still in the same place," noted John Finn, managing director of Treasury Solutions, a corporate finance consultancy. When the guarantee was detailed by Finance Minister Lenihan, he claimed it would be cheapest and most efficient way of resolving the financial crisis without affecting the whole economy. That's not the case now, with Ireland's banking sector and the nation's sovereign debt inextricably and expensively embraced in the economic future of the country — with ramifications for the Eurozone if they part ways.

"The fact that [the government] can't quantify the black hole is spooking the markets. There is a concern about the banks affecting the sovereign. When there is uncertainty, markets assume the worst," Finn says.

Cowen's government has little room to manoeuvre.

Between the mid-1990s and 2007, the Irish economy had expanded rapidly due to tax breaks, planned social policies, a concentration on the knowledge and bioscience economies and participating in the Eurozone with low European Central Bank interest rates. It was easy to meet the ECB's strict criteria on deficits.

Property bubble

According to the ESRI, Irish house prices increased by 300 per cent between 1996 and 2008, with the average home rising from 75,000 to 300,000 euros, compared to a total rise of 30 per cent in the consumer price index. The Celtic Tiger was roaring on the basis of a property bubble, one that was being fed by fast and loose lenders like FitzPatrick's Anglo Irish Bank.

It was over-exposed to a small number of high-rolling developers and construction companies investing in a superheated property market. And when the global credit crunch undermined confidence in the Republic's banks, the house of cards came tumbling down. To make matters worse, Anglo Irish hid loans to its directors from its shareholders, while an inner circle of property developers have been given preferential treatment to buy Anglo Irish shares, further undermining its liquidity.

The result has been a double whammy for Ireland's taxpayers. An emergency budget imposed tax increases on public sector workers, cut government services across the board, and created deep political unrest in an assault on the nation's education and health sectors.

Popularity nosedives

Recent opinion polls have put the popularity of the Fianna Fail-led coalition with the Green Party at less than 10 per cent. Cowen's fragile parliamentary majority was cast in doubt last week when an independent parliamentarian said he would no longer support the government because of the Anglo Irish Bank fiasco. Smelling blood, the opposition parties of Fine Gael and Labour have said they will no longer provide pairing arrangements for government members while on official business out of Ireland.

And to make matters worse, it appears as if the pressure of holding together Ireland's fragile finances is taking a personal toll on the prime minister.

Last week, seemingly hung over, Cowen spoke on national radio, causing even more outrage. It was an episode that caught the attention of US late-night host Jay Leno. He broadcast a photograph of Cowen, asking his audience if it was that of a bartender, a politician or a nightclub comedian. "He's Brian Cowen, the Prime Minister of Ireland," Leno said to loud laughter. "It's so nice to know we're not the only country with drunken morons." If Cowen's government fails to come to grips with the full 50 billion euro cost, there will be few laughing in bond market circles.