The silver lining to Trump’s Fed interference

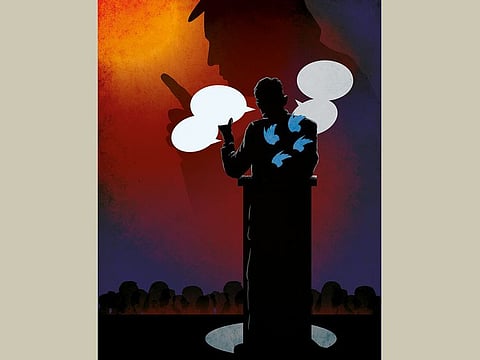

Jerome Powell now has the centre stage to publicly articulate Fed strategy

Donald Trump’s goading of the Federal Reserve — especially its Chairman, Jerome Powell, ironically a Trump appointee — to keep interest rates low is a sharp break from a multi-decade practice of US presidents publicly showing respect for the independence of Fed decision-making. One has to go back to President Nixon to find a White House that so overtly attempted to pressure the Fed in the open.

Today, Trump is following a marked interventionist pattern that is similar to some of his less-than-illustrious foreign counterparts, namely the central bank interventions by Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Perhaps Trump’s behaviour shouldn’t be surprising.

After all, he has an unorthodox approach to the presidency, manifested most visibly by his habitual Tweeting about nearly every matter, whether or not policy-related — from the economy to firing Cabinet secretaries.

But Trump’s economists in his Council of Economic Advisers (CEA) should know better. That is, if they can — or are willing — to tell him if there is one dictum above all else by which most central bankers the world over try to live, and whose stature and legacy are nearly wholly determined, it is operating with minimal interference from other parts of government.

During my time in the CEA in the early 1990s, we didn’t need to warn the then Commander-in-Chief that boxing-in the Fed — or even the perception of doing so — would actually undermine his own ability to get the US economy to perform in a way that would brighten his political fortunes. Every Economics 101 student, surely those who pass through the Wharton School of Business, from which Trump graduated in 1968 with a B.S. in Economics, is taught why ensuring the Fed’s independence — at least trying to adhere to its principle — is sacrosanct if the bank is to be effective in achieving its principal enunciated monetary policy objectives: combating inflation, promoting full employment, and maintaining the nation’s financial stability.

“Independence” in monetary policy-making is actually a bit of a slippery concept among us economists. Around the world, it is not uniformly defined or practised. In fact, central bank legal structures do vary internationally.

Any chair of the US Fed knows it is unrealistic to believe he or she will be immune from pressures from the White House, the Treasury Department or other political forces. Still, they will try to bend over backwards, including possibly face pressure from other Fed Governors, to even consider pre-emptive policy decisions to ensure their credibility is untarnished both among the US population and throughout world markets.

The Fed’s structural mechanisms engendering independence — its decisions are not subject to ratification by the Executive Branch; it is self-financed; and the members of its Board of Governors are appointed in staggered fashion and serve 14-year terms (thus not overlapping with presidential terms, unless there are resignations) — are necessary conditions.

But they are not sufficient. That would be so only if the Fed is shielded from the tactical pressures of day-to-day politics so it can focus squarely on the long-run economic health of the country. Trump’s overt actions pose more than the usual challenge of interference as to how the Fed will conduct its business.

In light of Trump’s proclivities, going forward what does the Fed’s decision-making calculus for monetary policy look like? Here are potential scenarios.

Any notion that the Fed will buckle under to Trump’s rants is far-fetched. If the serious policy consequences of that — most notably the loss of confidence in the US dollar and its erosion from being the globe’s medium of exchange, not to mention US economic instability — wouldn’t be enough, no Fed chair relishes getting hauled before Congress. Its wrath — across both party-lines — would be severe.

Will the Fed try to show its muscle and take steps to deliberately counter Trump to prove its independence even if such moves are not justified by economic conditions? Some in the Fed might be tempted to make such a mark. But you can bet Chairman Powell won’t engage in any public tit for tat with Trump. Powell knows that would only fan Mr. Trump’s flames.

Nor is it likely the Fed will be hamstrung by the President’s Tweets. There’s a robust culture of independence ingrained throughout the Fed’s professional staff and its Board of Governors. Although they won’t become captive to Trump, an activist President surely complicates their manoeuvring at a time when the Fed’s decision-making already will be decidedly tougher going in the near- to medium-term.

Unemployment has reached historic lows; the 2017 cut in corporate income taxes significantly enlarged the Federal deficit; and, the Administration’s trade wars have cast a pall on the prospects for growth, not just in the US but globally.

All told, delicacy will be the name of the policy game for the Fed, even more than usual.

So, in this setting what’s a Fed chairman to do? Powell’s best defence against Trump is not offence. Nor is it to come across as being defensive.

Rather, his best strategy should be to embellish the sound practice pioneered by his two immediate predecessors, Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen. Take a decidedly proactive approach and explain directly to the American public and international financial markets the nature of the Fed’s policy stance and why certain decisions have been made.

Moreover, unlike Bernanke’s and Yellen’s predecessor, Alan Greenspan, who was famous for obfuscation, Powell should focus on communicating using a lexicon the average citizen will understand. Ironically, actions by Powell along these lines could be a silver lining from Trump’s meddling into the Fed’s affairs.

—Harry G. Broadman is Managing Director and Chair of the Emerging Markets Practice at Berkeley Research Group and faculty member of Johns Hopkins University.