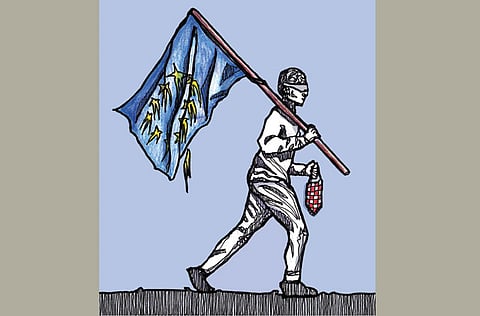

Croatia not zealous about EU accession

Citizens fear becoming a second-tier state alongside their Mediterranean neighbours

As Zagreb’s famous clock rang in the first day of the new month, Croats readied themselves for a fresh chapter in their country’s turbulent history. Processions lined the streets while fireworks filled the sky and Brussels’ top bureaucrats perfected their Croat to welcome the European Union’s (EU) newest 4.5 million members in their own tongue. But turn the TV cameras off and your average Croat is less enthusiastic about EU accession, as I discovered on a recent trip to Zagreb.

From shopkeepers to bartenders, florists to bakers, six out of 10 people I asked said the EU would be a bad thing for Croatia. Two said they didn’t know or care, while two more thought membership would bring benefits for both sides.

That’s hardly a vote of confidence in the European project from a country which you’d have thought would have more to gain than lose by entry. Delve deeper into the reasons for their pessimism and it’s clear what Croats fear most is becoming a second-tier state alongside their cash-strapped Mediterranean neighbours.

Some of those interviewed spoke of ending up as “a workhorse of Germany”; others reckoned the country was joining the party too late when the benefits on offer weren’t as attractive. And now as Croatia’s government drags its citizens begrudgingly into the EU, their ambivalence and economic woes will further undermine confidence in a bloc whose biggest members are themselves threatening to pull out, like the UK.

Let’s be frank: if asked, most Europeans would probably admit Croatia deserves its place in the group... if only from a cultural point of view. But take a look at its economy and the figures are frightening: youth unemployment stands at over 50 per cent while the economy is languishing in a five-year recession.

Mountains of red tape

Sitting down to a cup of bitter Croatian coffee, two young entrepreneurs asked themselves with hefty irony why their people went through an appalling civil war to surrender their hard-won sovereignty to faceless eurocrats. It’s true, they said, some €11 billion (Dh52.7 billion) of EU restructuring funds lie in wait for Croatia but so do mountains of red tape which could stifle the republic’s nascent small businesses.

Already fights are looming over a myriad other issues: from banning Croatia’s famous Prozek wine to protecting its Italian namesake Prosecco to unease over EU plans to legalise gay marriage. Such ructions will only get worse if growth is not forthcoming on either side.

Ten years of dancing to Brussels’ tune hasn’t helped to raise living standards for most Croats. As a result, support for EU membership in the country has collapsed. A referendum last year put Croatian support for the plan at 66 per cent. Yet, by the time the country joined, less than half of its inhabitants were said to be pro-Europe, according to recent polls.

At just $12,971 (Dh47,643) last year, Croatia’s per-capita GDP (gross domestic product) is paltry when compared with the Czech Republic’s $18,579 and the $41,512 of Germany, showing Croatia has a long way to go to climb up the EU rich list.

Even before Croatia begins to reap the benefits of increased intra-EU trade, the country faces losing its best and brightest, as young talent moves abroad to escape one of the lowest average wages in Europe.

Fears of brain drain

In an interview last month, Croatian Prime Minister Zoran Milanovic — himself a committed Europhile — confessed to me one of the things he feared most was a brain drain.

Re-born from the ashes of Europe’s bloody Balkan wars, after years behind the iron curtain, Croatia is the second former Yugoslav nation to qualify for EU status after Slovenia. It’s true that membership of the elite club would help shield the country from further Balkan unrest but Croats seem doubtful it will offer a path to prosperity.

Indeed, take the example of Slovenia: nearly a decade on since joining both the bloc and the single currency, its banking system has all but collapsed and the country risks becoming the next Cyprus.

EU membership is not the golden chalice it once was. A lesson Croatia may learn the hard way.

— The writer is the host of CNN International’s twice daily ‘World Business Today’ programme.