Beirut: Once a distant dream for a handful of minorities scattered throughout the Middle East, federalism is suddenly starting to become a not-too-distant aspiration, thanks to the recent vote in Iraqi Kurdistan, which goes hand-in-hand with the break-up of strong central governments in Iraq and Syria.

Speaking about the latest Kurdish elections in northern Syria, senior diplomatic editor at the London-based Asharq Alawsat, Ebrahim Hamidi said: “Pre-2011 Syria is over and a new social contract is emerging. There will be federalism, decentralisation, and a weak central state.”

An expert on Kurdish affairs who has been reporting on their politics for three solid decades, he told Gulf News: “I think that the Kurdish leaders in Syria have been smart so far. They have realised that they cannot copy the model of Iraqi Kurdistan because there is no clean Kurdish region in Syria. By going for federalism, they are actually achieving their goals and through the Syrian Democratic Forces (a US-backed Kurdish army) they are now in control of one third of Syria.”

On Wednesday, Syrian Foreign Minister Walid Mua’alem accused Syrian Kurds of competing with the Syrian army for control over oil-producing areas.

“They are now drunk on US assistance and support. But they need to understand that this assistance won’t last forever,” he warned.

But it remains to be seen, how the Syrian regime — weakened by the country’s six-year war — plans to retaliate.

More and more ethnic and religious groups in the region are toying with the idea of federalism.

When ranking British-American scholar Bernard Lewis peddled the idea back in 1980, intellectuals throughout the Arab World scoffed at him, ridiculing the idea as a “Zionist-backed conspiracy.”

The former Princeton University professor advocated granting local autonomy to a plethora of squabbling ethnic and sectarian minorities throughout the Arab World, in order to keep them under watchful control.

In 1992, he wrote a more detailed thesis.

Three years ago, former US Vice-President Joe Biden wrote a piece for The Washington Post, peddling the idea of creating “functioning federalism” in Iraq.

It was automatically seconded by the Kurdistan Democratic Party, headed by president of the Kurdistan Government Massoud Barazani.

Already in Syria, plans for a federal referendum are underway. On September 22, Syrian Kurds voted for 3,700 communes.

Municipality elections are earmarked for November 3, followed by parliamentary ones on January 19 2018.

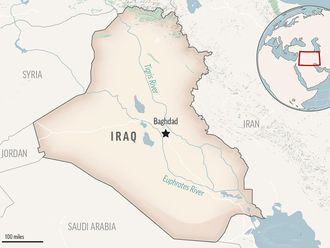

Realising that they don’t have territories that are 100 per cent Kurdish, and that even then, they are separated by land and river, Syrian Kurds have settled for a federal system that grants them their full rights in three cantons: The first would be in Al Hassakeh and it would include the city of Al Qamishli, both east of the Euphrates River. The second would be immediately south of the Turkish border, including the towns of Kobani and Tal Abyad.

The last would be in Shahban in the Aleppo countryside and Afrin, west of the Euphrates, the only major Kurdish city falling within Russia’s fiefdom.

The back-to-back referendums in Syria and Iraq will likely trigger the emotions of the region’s Kurds, scattered across Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria.

It could also inspire other minorities in the region, like Iranian Sunnis, for example, Druze, Christians, and Yazidis, who have not yet reacted to the latest developments, waiting, perhaps, to see whether Iraq, Turkey, and Iran — all of whom are threatening war against Iraqi Kurds — act on their words.

The Kurds of Iraq back in 1991 were granted limited autonomy after a string of devastating events. Iraqi autocrat Saddam Hussain put down a Kurdish rebellion in the mid-1980s, eradicating pockets of Kurdish resistance in the north and inflicting mass punishment on the Kurdish community, which included the uprooting of thousands of Kurds from the homes and replacing them with ethnic Arabs.

In March 1988, Saddam attacked the city of Halabja in southern Kurdistan with chemical weapons, massacring anywhere between 3,200-5,000 Kurds.

In the spring of 1991, he suppressed a Shiite rebellion in the south, killing an estimated 100,000 people.

Both groups vowed revenge, and they succeeded after the downfall of Saddam’s regime in 2003.

Slowly and steadily, the Kurds pushed forth with their quasi-independence, all the way up to the September 2017 referendum.

Meanwhile, Iraqi Shiites have created a full-fledge mini-state in southern Iraq, with the strong backing of Iran.

They have emerged as possibly the strongest players in the post-Saddam Iraq, therefore they have no incentive to break off with Iraq since they stopped taking orders from Baghdad for years.

Iraqi Sunni tribesmen and former Baathists tried, with limited success, to create their own fiefdoms, first via Al Qaida and then, through Daesh, overrunning important cities like Tikrit and Mosul.

That project is now over as the Iraqi army along with powerful Shiite militias have largely driven the militants out.

Sunni disenfranchisement in Iraq after the fall of Saddam was one of the main factors that drove many to join extremist groups.

If such discrimination and oppression against Sunnis continue in a post-Daesh Iraq, the Sunnis will likely mobilise again — although it remains to be seen what form that could take.

Some in the Druze and Alawite community of Syria toyed with the idea of federalism back in the 1930s, and so did the Shiites and Kurds of Iraq under Saddam Hussain. None of these projects bore fruit in the past, due to strong central governments that suppressed separatist movements.

Had the regime collapsed and been replaced with a government led or inspired by political Islam, then they too would have pushed for secession, investing in the breakdown of law and order in Damascus.

Heavyweight Kurdish leader Salih Muslim, who helped engineer a special vote for Kurdish communes in northern Syria on September 22, thinks that federalism is a great idea for Syria and even the region.

If it succeeds in northern Syria, it might be copied by the Druze in south, or by the Sunnis of Idlib in the Syrian northwest.

Speaking to Gulf News, the chairman of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), noted: “We think that it is the only way to preserve the unity of Syrian soil. Federal systems are found all over the world, even in Russia and the US. Why is it legitimate for them and prohibited for us?”

“Only when people are free and can decide their own future, can true democracy take form,” he said.