Tough fight lies ahead for west Mosul

Iraqi forces find dangerous and fairly sophisticated weapons left behind by Daesh militants in east Mosul

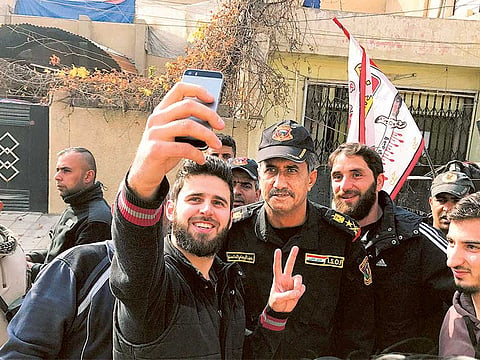

Mosul: Residents of east Mosul held up their children and took selfies with Iraqi counter-terrorism commander Lieutenant General Abdul Wahab Al Saadi after his men cleared Daesh fighters from their neighbourhoods.

But his tour on Saturday of homes once occupied by the militants was a reminder of the dangers ahead as security forces prepare to expand their offensive against Daesh militants into west Mosul.

Flanked by bodyguards in the Mohandiseen neighbourhood, Saadi got a firsthand view of Daesh’s meticulous planning and reign of terror as he moved from house to house, greeted by locals as a hero.

In one home were a set of instructions on how to make bombs.

A large bucket was filled with screws that were packed into explosives to kill and maim. Beside the leaflets were a pair of industrial rubber gloves, wires and detonators.

Nearby a thick book described how to use Russian machine guns. Militants were also well-versed on how to employ anti-tank missiles.

The battle for Mosul, involving 100,000 Iraqi troops, members of the Kurdish security forces and Shiite militiamen, is the biggest ground operation in Iraq since the US-led invasion of 2003.

Iraqi security forces have retaken most of east Mosul, with the help of US-led coalition airstrikes which flattened rows of buildings in Iraq’s second-largest city.

The next phase, expected to kick off in a few days, could prove more difficult.

Western Mosul has many narrow streets and alleyways that tanks and other large armoured vehicles cannot pass through.

Militants are expected to put up a much tougher fight to hold on to their last stronghold in Iraq.

“We expect to enter the west in the next few days,” said Saadi, shortly after tearing down a Daesh poster in anger.

Mosul, the largest city held by Daesh across its once vast, self-proclaimed caliphate in Iraq and neighbouring Syria, has been occupied by the group since its fighters drove the US-trained army out in June 2014.

Its fall would mark the end of the caliphate but the militants are widely expected to mount an insurgency in Iraq and inspire attacks in the West.

The group’s determination and organisation were evident in several homes toured by Saadi.

Laminated guides on the range of various weapons could be found on the floor or on tables.

One house was clearly dedicated to the production of small drone aircraft used for both surveillance and attacks. Several lay scattered on the floor.

A document with Daesh logos asked detailed questions about the type of drone mission, either bombing, an explosive aircraft, spying or training.

There was section on who will manage the aircraft’s power on any particular mission and a checklist on structural integrity.

Daesh ruled eastern Mosul with zero tolerance for dissent, routinely shooting or beheading anyone branded an opponent to their radical ideology.

Saadi’s men were tipped off Daesh had converted a villa on the street he was standing on into a prison and torture chamber. People were held on the top floor in rooms with steel bars.

“We were told that the neighbours would hear screaming from the house,” said Saadi. “They imprisoned anyone that challenged them. Anyone who refused to fight for them.” Across town, overlooking the Tigris River dividing east and west, the former Ninewah Oberoi Hotel offered another glimpse into Daesh, which changed its name to Hotel of the Inheritors.

“It was a place for them for the gatherings of the foreigners (fighters) and suicide bombers,” said Saadi, standing on the hotel’s rooftop. “Five stars ... in order to encourage them.” Gunshots rang out, and explosions could be heard, a precursor to the upcoming campaign in west Mosul.