Australia likes to refer to its battlefield dead, especially in the first and second world wars, as “the fallen”, whose bodies if found were “laid to rest” in picturesque, peaceful cemeteries of blonde statuary and Rosemary bush.

Their politicians invest significantly in commemorating them (some $600 million-plus, or Dh2.2 billion, alone for First World War centenary events), and into finding, identifying and reburying those whose bodies the mud may surrender many decades later.

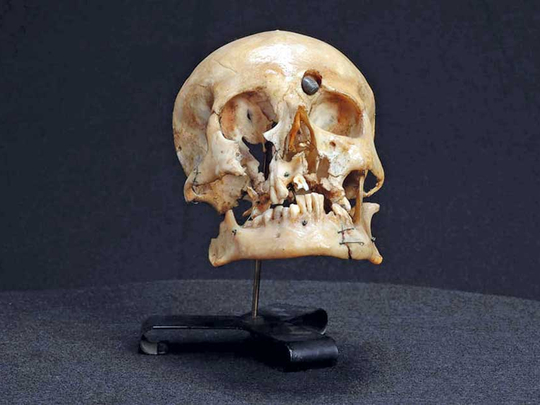

So it is surprising to find the skull of a First World War Australian Anzac soldier, replete with the shocking facial injuries that killed him a century ago this week, featured online in an American medical museum’s grizzly collection of sometimes freakish exhibits.

The skull, part of the collection of the Mutter Museum at the College of Physicians in Philadelphia, tells a shocking and tragic story of battlefield violence and intolerable physical suffering that official commemoration — with its almost ecclesiastical language of the fighting Anzac “spirit”, the “fallen” and their “sacrifice” — all too often overlooks.

On September 28, 1917, the Anzac was shot in the mouth during the Battle of Polygon Wood (known also as the Third Ypres, part of the Battle of Passchendaele) in Belgium, and his right jaw destroyed by shrapnel while another bullet — still visible in his skull — struck his left sinus.

The museum’s explainer reads:

This Australian soldier’s skull has extensive damage caused by bullet wounds sustained in the Battle of Passchendale (or Third Ypres, Battle of Polygon Wood) in the First World War. He was shot on September 28, 1917. Most of the damage was caused by a lead bullet that entered the mouth and passed through the palate and right eye. Shrapnel destroyed the ascending ramus of the right jaw, and another bullet, visible here, struck the left frontal sinus.

Philadelphia ophthalmologist and surgeon W.T. Shoemaker treated this soldier at a battlefield hospital in France. This soldier survived his initial injuries and treatments. But, five days after his injuries, blind and disoriented, he pulled out the bandage materials in his mouth that packed the wounds. He bled to death.

It says Shoemaker donated the “Adult skull with ballistic trauma” to the museum in 1917, making possible an inference, of course, that the ophthalmologist removed the head from the battlefield hospital. It’s hard to imagine what, if any, consent was involved.

Click on the icon reading “OUCH” and the illustration highlights the shrapnel damage to the soldier’s jaw, or, on the one reading “THE END”, to see a close up of the hole in his cheek that had been packed with bandage. “Pulling out the material that packed this space is what killed our soldier,” it explains.

The Anzac skull certainly tells a story of a terrible battlefield death. But as is so often the way when human remains become institutional collection items, it is stripped of human identity and past beyond the moments of injury and death. It is objectified by death, not what life — rich and interesting or otherwise — preceded it.

And, so, unfortunately, we know precious little about who this Anzac is. We don’t have his name or know who his family is or where he came from. Was he Indigenous or white? Even had he contemplated dying in war (what soldier who volunteers to go off and fight does not?) could he ever have imagined that his head would become a museum collection item and an object of popular curiosity?

If the Mutter Museum knows any of this, it is not letting on.

Despite my repeated requests, the museum has not detailed how: it acquired the Australian’s head; whether the rest of his body is in the museum or buried in a war cemetery; if the museum is privy to the dead man’s identity and whether the skull has been on temporary or permanent public display.

It is, in fact, likely that the rest of the body is buried at either Polygon Wood Cemetery or the nearby Buttes New British Cemetery. In the past decade the bodies of several Anzacs who died in fighting around Polygon Wood have been unearthed on local properties. Several have been identified using DNA techniques. All have been officially re-buried with either “known unto God” headstones or memorials bearing their re-established identities.

It is understood that the Australian Army’s office of Unrecovered War Casualties — which is mandated with recovering and identifying unaccounted for military personnel, is aware of the Mutter Museum’s Anzac skull and is making inquiries, possibly through the Australian Embassy in Washington.

Mutter describes itself as “America’s finest museum of medical history” which “displays its beautifully preserved collections of anatomical specimens, models, and medical instruments in a 19th-century ‘cabinet museum’ setting. The museum helps the public understand the mysteries and beauty of the human body and to appreciate the history of diagnosis and treatment of disease”.

The Anzac skull is part of a collection that also includes “the soap lady” (a body exhumed in Philadelphia in 1875), Albert Einstein’s brain, Dr Joseph Hyrtl’s human skull collection, a plaster cast and the conjoined liver of “Siamese twins” Chang and Eng Bunker, the jaw tumour of President Grover Cleveland, and hundreds of body parts that illustrate disease and terrible war injuries.

The fourth and fifth divisions of the Australian Imperial Force suffered more than 5,700 casualties at the Battle of Polygon Wood, which began on 26 September 1917. It was the most devastating year of the war for the AIF; 12,000 Australians died in the extended battle of Passchendaele alone and 30,000, mostly on the western front, for the year.

From a population of less than 5 million in 1914, some 324,000 Australians enlisted and served overseas, and 61,720 died. Most are buried in official war graves close to the battlefields or field hospitals where they died. But tragically some 18,000 who died on the European western front were either never found or could not be identified at death.

The Anzac whose skull is displayed by Mutter would be ranked with the missing even though the museum might well be in a position to help name him due to the medical and personnel records that would have formed part of his battlefield treatment.

Meanwhile, the display of the skull is anomalous with official Australian policies to remove from public display and repatriate human remains (overwhelmingly belonging to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander ancestors) that are held by foreign collecting institutions — mostly museums and medical schools.

The National Museum of Australia has the remains of about 500 individuals that it has repatriated to Australia from foreign institutions but, for various reasons mostly to do with unestablished identity, has been unable to return to country.

The South Australian Museum, which has the largest collection of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander material culture in the world, holds the remains of several thousand Indigenous people.

The government has dedicated minimal resources and energy to the identification and repatriation of Indigenous remains, however. As Australia prepares to commemorate the AIF’s actions at Passchendaele and Polygon Wood this week, the official response to the Mutter Anzac skull display will, therefore, be most illuminating.