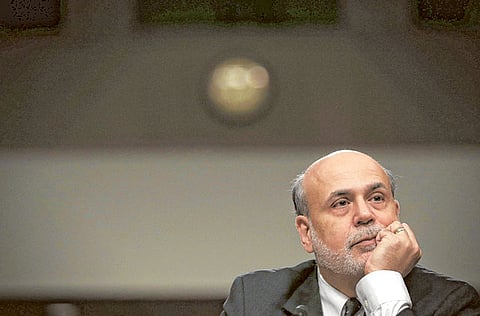

Pressure on US Fed chairman

Much to be said in favour of Ben Bernanke being given an extension

London: The US economy is on the mend. Most recent indicators suggest that, five years after the start of the Great Recession, the “L-shaped” recovery is finally heading north. The stock market is booming, and home prices are on the upswing. The rising price of houses makes people feel richer, and consumer confidence is on the mend. Private borrowing is up, and consumers are starting to spend again.

Growth is not great, at about 2.5 per cent to the end of the year, when the post-war average is 3.2 per cent, but it is steady and appears to be self-sustaining. And this despite the 1.5 per cent reduction on what growth would be were it not for the clumsy sequester’s fiscal drag.

The general outlook is bright, if not sunny. As Winston Churchill said after the Battle of Alamein: “This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

Why whisper this good news? Because the idea that we have achieved recovery suggests to some it is time for the Federal Reserve to change tack. Monetary policy is the only instrument the administration has left. Hampered by a hostile House of Representatives, President Barack Obama’s “jobs bill” to stimulate the economy is long forgotten. Even he doesn’t mention it anymore.

But the Fed has a medium-term strategy that means keeping interest rates low so long as unemployment remains stubbornly high. It therefore plans to continue pumping money into the economy through quantitative easing at the rate of $85 billion a month to the horizon. The last meeting of the Fed’s board maintained a steady-as-she-goes policy, with the usual suspects in the minority anxious about the inflationary implications of quantitative easing.

There is no inflationary pressure, nor is there likely to be. The austerity policies of the EU, the only rival to America in terms of size and sophistication of economy, have pushed the euro bloc into recession and are keeping the euro weak. The same is true of Britain, where austerity has led to a near-triple-dip recession and sterling is trading lower.

America’s old trade rivals the Japanese are on a QE binge, and the yen is sinking fast. As the world’s biggest economy is still growing, there has been a flight to the dollar that has pushed up the exchange rate and kept domestic inflation down.

Month by month we can expect more pressure on Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke to put his foot on the brake, reduce or stop altogether the QE programme and allow interest rates to rise. There are endless siren voices urging him to alter course now. Like health insurance adjusters who patrol hospital wards looking for malingerers, the argument is: If the economy is on the mend, why do we need to keep taking the cure?

It is such a relief to have finally escaped from the worst recession in 80 years that it is natural to want to get back to “normal,” even though we know that since the traumas of 2008-09 nothing will ever be quite the same. The same temptation to return to the old ways lured Franklin Roosevelt to prematurely abandon his New Deal stimulus measures in 1937.

The result was “the Roosevelt Recession,” a wrong turn in the history of the New Deal that both progressives and conservatives prefer to forget because of the unnecessary pain caused by braking too soon.

In brief: In 1937 Felix Frankfurter persuaded FDR, whom John Maynard Keynes rightly pointed out knew little to nothing about economics, that blue skies were ahead and it was time to adopt what today we would call austerity measures. In 13 hellish months, unemployment leapt from 14.3 per cent to 19 per cent and output collapsed by 37 per cent. America only resumed its sputtering recovery after congress in early 1938 passed a bill to boost government spending.

The key today to maintaining our steady growth and avoid sliding back into recession is not the new chairman of the president’s Council of Economic Advisers, Jason Furman, whose elevation signals more of the same. It is who the president picks to succeed Bernanke, who is expected to step down after two terms as Fed chairman in January.

Bernanke was born to be Fed chairman in the middle of a financial crisis. He literally wrote the book about the Great Depression and used the lessons learned from his studies to avoid repeating the mistakes made 80 years ago that caused our great-grandparents such protracted misery. There was no better time for someone with a profound knowledge of the history of economic thought to be in charge of the Fed than when the financial slump broke over our heads in 2008.

Bernanke was a keen student too of Milton Friedman, whose research with Anna Schwartz led to him blame the Fed’s over-tight monetary policies in the 1920s for provoking and then exacerbating the Great Depression. On Friedman’s 90th birthday, Bernanke offered an extraordinary mea culpa on the Fed’s behalf. “Regarding the Great Depression,” he said, “you’re right, [the Federal Reserve] did it. We’re very sorry. But thanks to you, we won’t do it again.”

Much to the discomfort of conservatives devoted to the memory of Friedman, Bernanke was as good as his word. His policy of quantitative easing has been a textbook monetary response to a flailing economy.

His departure will spark a feisty nomination battle that puts monetary policy at the heart of the Senate’s business. Even if the president were to name to the post Paul Volcker, the Democrat appointed Fed chairman by Jimmy Carter who licked inflation under Ronald Reagan, the sound-money proponents would say he was too soft a touch.

There are a number of good candidates the president could pick who would follow Bernanke’s lead in ensuring there is no premature return to a curb on borrowing through high interest rates. Their general views on when to tighten the money supply and their commitment to putting joblessness ahead of inflation as a priority are similar.

Currently the “Fed Chairman Stakes” puts former Clinton Treasury secretary and Harvard President Larry Summers a nose ahead of former Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner and Federal Reserve Vice-Chair Janet Yellen. Any of the three would be a good fit.

But each is sure to attract a protracted and bitter nomination battle that would be worth avoiding with the mid-term elections not far off. The GOP leadership is behaving more like a protest movement than a party of government and its Tea Party supporters will brook no compromise. After the stiletto-ing of Susan Rice, some may feel it is time to take another hostage.

There is, however, a bolder selection that would avoid the need for a nomination scrap altogether and would ensure perfect continuity: having Bernanke stay at his post.

There are no term limits to oblige the Fed chairman to stand down. Bernanke let it be known “through friends” he wanted to depart the stage in the run-up to the presidential election when Mitt Romney, like every other Republican presidential hopeful, appeased his donors by pledging that his first act on entering the White House would be to fire Bernanke.

Bernanke’s comment at the time the rumours started swirling was hardly a plea to be allowed his freedom. “I am very focused on my work,” he said. “I don’t have any decision or any information to give you on my personal plans.”

In the absence of any pressing personal reason for stepping aside, it would make perfect sense if Bernanke were to see out the job he began. The Great Recession is not yet licked.

He has not completed the task history dealt him. He is every bit as good as the person who would succeed him. Now is a goo