Dubai: To put it mildly, the past four years have been somewhat difficult for the members of the Eurozone.

And the European Union itself has struggled to manage the fallout of bailouts for Greece, Cyrpus, Ireland and Portugal, with the elected Parliament and the executive European Union commission trying to find new ways to deal with the political and economic fallout of the crisis.

But there’s also a reality that this artificial union of 28 members — Croatia joined access to the exclusive European club on July 1 — is actually durable and has managed to weather the worst of the crisis.

And considering that the Euro was adapted by 17 members without there actually being a common bond mechanism to self-regulate the currency market, not a member of the Eurozone has yet left.

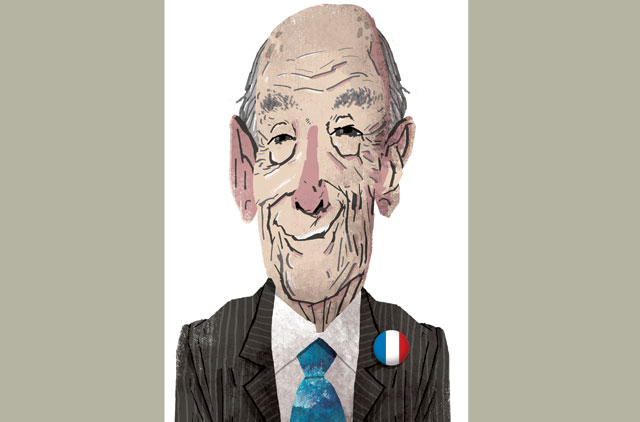

Valery Giscard d’Estang must be more than a little pleased with his brainchild as he sits back in retirement place near Auvergne in France’s central heartland. It was he as French President, along with German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt who set the wheels in motion for a closer Europe, tied by common political and social policies from Madrid to Malmo, economies spending the same currency from the Baleric Islands to the Baltic Sea.

This was always his strong point, able to deliver master strokes formed by a sharp intellect. From French provincial gentry, his family purchased the noble-sounding d’Estang to add grandeur to its conservative values.

D’Estang knows the ins and outs of uniting Europe’s nations and economies better than most. Patrician and paternalistic, he is French arrogance personified, never listening to others, forging ahead with his grand plans.

Even his enemies admit that he was brilliant when it came to shaping Europe, creating the European Council of heads of government, having the European Parliament elected directly; and establishing monetary union that gave birth to the Euro.

Giscard was elected to parliament at the age of 30, having sailed through France’s top two higher education establishments, the Ecole Polytechnique and the Ecole Nationale d’Administration.

Even Charles de Gaulle needed his intellect, although in private he found him difficult and didn’t really like him.

In a campaign to soften his reputation as a cold brain box, he played the accordion on television, wore tatty sweaters, and invited Paris dustmen in off the street for breakfast at the Elysee Palace — but expensive truffles he served with the eggs rather spoilt his game.

He still blames his 1974 defeat on a scandal that blew up over his relationship with an African tyrant, Jean-Bedel Bokassa. They hunted big game together in the Central African Republic before Bokassa was tried and convicted for cruelty against his people. In the fallout, d’Estang forgot to claim a set of diamond cuff links as an official gift, he was hounded by the press.

Seldom have a German chancellor and a French president seen eye to eye on so many economic and fiscal policy issues as Schmidt and d’Estang, 86. During their terms in office, which began in 1974, both had to deal with the oil crisis, stagnating economic growth, rising inflation and unemployment.

After the demise of the Bretton Woods international monetary system, in which the dollar served as the world’s key currency, they strongly advocated the introduction of the European Monetary System with stable yet adaptable exchange rates and the European Currency Unit — the administrative unit that became the Euro — as the standard unit of account.

In 1975, their efforts also led to the founding of the Group of Six which consisted of the world’s leading industrialised countries — France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the UK and the US — which met once a year for a global economic summit. After they were voted out of office (d’Estang in May 1981, Schmidt in October. 1982), they both remained true to their European ideals. In 2001, d’Estang was elected chairman of the European Convention, which was tasked with drafting a constitution for Europe. To this day, the two statesmen have maintained a close friendship.

To even question of the future of the Euro is anathema to d’Estang.

“The euro will certainly be around longer than us.,” he told Der Speigal in a recent interview. ... Why don’t you ask for instance whether the US dollar will still exist in a few years’ time, or the Japanese yen or the Chinese yuan?”

And debt levels in Europe are not a reason for concern, he believes. “The Euro is the currency of a region that has less debt than the dollar zone, a huge trade surplus and a well-managed central bank. Its current exchange rate to the dollar is above the introductory exchange rate in 2002. Why all the doubt?”

He left office in 1981 but few still know the man, aloof and alone, even if the veneer is slipping slightly, as in the case of his telling of an encounter with a panda bear.

He said he had been visiting Vincennes Zoo in Paris, where his daughter was on work experience, when he decided to test his “presidential courage”.

A panda leapt on him and staff had to free him from its claws.

The pandas, he said, had been a gift from China to his predecessor as president, Georges Pompidou.

“They came to extract me from its claws but imagine what would have been said had the animal knocked me to the ground,” the famously tall president — he is 1.89m — remarked to laughter from his audience at a recent conference.

D’Estang is often regarded as the most cultivated and most aristocratic of recent French presidents, if not the most pompous. But his work in Europe still endures.