When parents ask how they can comfort and reassure their children after a tragedy that receives extensive news coverage, the usual advice is to be supportive and reassuring but don't offer false assurance, experts say.

"Children want to know they're safe and will stay safe. Parents can convey that by what they say and how they behave," said Dr. Victor Fornari, director of child and adolescent psychiatry at North Shore-LIJ Health System in New Hyde Park, New York.

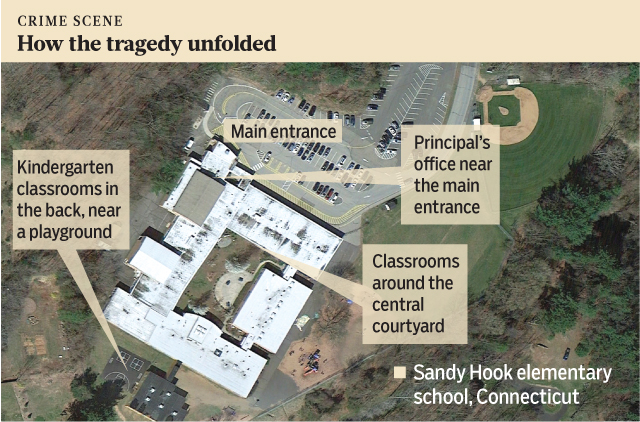

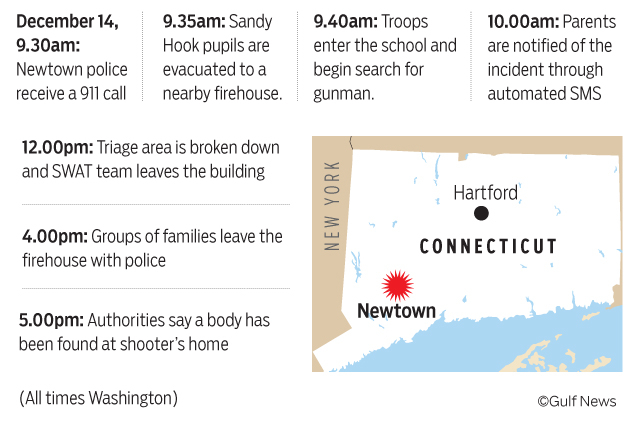

But after a school shooting - especially one as horrific as that in Newtown, Connecticut, on Friday - the challenge of helping kids cope is enormously greater than after, say, a tornado wipes out a distant town. It also poses a much greater risk that children who hear about it will suffer a traumatic reaction.

"Schools are supposed to be safe and nurturing environments for children," said Fornari. "This shatters that belief. Restoring the sense of security in school will take time."

The way to do that isn't to offer false assurances, experts say.

"I wouldn't lie, because your credibility is very, very important," said Dr. Michael Brody, a child psychiatrist and chairman of the Television and Media Committee of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. "To say this would never happen to you, I don't think that is reasonable."

But while parents need to be honest, they should also make clear that such tragedies are exceedingly rare.

"Parents can say emphatically, 'your school is a very safe place,'" said David Finkelhor, professor of sociology and director of the Crimes Against Children Research Center at the University of New Hampshire in Durham. "It's a vanishingly rare occurrence, and schools are still the safest places kids can hang out in terms of violence."

Parents should not let young children watch news coverage of the shootings, and might warn older children and teenagers away from looking for news and disturbing video of the tragedy on Twitter, Facebook and other sites they can access via smartphones.

Avoid upsetting details

As parents talk to their children about Newtown, they should avoid dwelling on upsetting details, such as exactly what the gunman did where and to whom. Younger children should be reassured that the shooting is over. With older children, parents might talk about their school's safety protocols and emergency plans.

If a teenager argues that school wasn't safe for Newtown's children, parents can offer statistics. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show that school homicides have fallen in the last 20 years from about 30 a year in the 1990s to 17 in 2010, the last year with complete data.

If the child has questions, parents should answer directly and in a straightforward way, said Dr. Joshua Kellman, clinical associate of psychiatry at the University of Chicago Medicine, matching the level of the response to the level of the child. If an 8 year old asks how someone could open fire on little kids sitting at their school desks, simply explaining that "sometimes something goes wrong with people and they are not thinking right," should suffice, he said.

It can also be helpful to show children that normalcy prevails. The best way to do that is by sticking to standard weekend activities, said child psychologist Dr. Harold Koplewicz, president of Child Mind Institute, a nonprofit treatment, research and education organization in New York City. "Go Christmas shopping, go to church or synagogue, play a game, watch a video."

Parents should keep in mind that grief, distress, anxiety and worse are normal human reactions to news that little children have been gunned down in their classroom, not signs of psychological illness. In other words, don't assume that children who become clingy or withdrawn, who demand more parental attention, stop doing schoolwork, have trouble sleeping or regress (parents can expect young children to ask to sleep in their beds, said Fornari) need counseling.

"If their reactions do not seriously interfere with their lives, you shouldn't necessarily seek out professional help," said Fornari. "Children are resilient. Most will be able to cope with this traumatic event and be fine."

The children who will have the hardest time coping are the 10 percent or so who already suffer from anxiety, typically as a result of an earlier trauma such as witnessing violence or losing a close relative, said Fornari. "Parents know if this describes their child, and should expect stronger reactions."

That, of course, holds especially true for the survivors of the shooting. These children -- and adults -- are more likely to be psychologically traumatized, suffering flashbacks, nightmares and intrusive thoughts, re-living the sounds of gunshots and the chaos of being rushed out of their classrooms by police officers.

For them, said Fornari, "their lives will forever be marked as before and after December 14."