Washington: California scientists are hunting ways to predict who's about to have a heart attack, and they say they've found a key clue.

Most heart attacks happen when fatty deposits in an artery burst open and a blood clot forms over the damage, blocking blood flow. Today's tests can't tell when that's about to happen.

On Wednesday, researchers at Scripps Translational Science Institute report they found deformed cells floating in the blood of 50 people who'd just had a heart attack, cells that had flaked off the lining of arteries. The study couldn't determine how early those cells appear before a heart attack. To start finding out, the researchers developed a blood test they plan to study in people with chest pain.

The study appears in the journal Science Translational Medicine. Dr. Eric Topol, director of California's Scripps Translational Science Institute said his team soon will begin needed studies to learn how early those cells might appear before a heart attack, and if spotting them could allow use of clot-preventing drugs to ward off damage. Some San Diego emergency rooms will study an experimental blood test with chest-pain sufferers whose standard exams found no evidence of a heart attack, he said.

Don't expect a test to predict heart attacks any time soon - a lot more research is needed, caution heart specialists not involved with the study. But they're intrigued.

"This study is pretty exciting," said Dr. Douglas Zipes of Indiana University and past president of the American College of Cardiology. It suggests those cells are harmed "not just in the minutes prior" to a heart attack, he said, "but probably hours, maybe even days" earlier.

"It's a neat, provocative first step," added Dr. William C. Little, cardiology chief at Wake Forest Baptist Medical Center. "But it is not a biomarker ready for prime time."

About 935,000 people in the U.S. have a heart attack every year, according to government figures. Doctors can tell who's at risk: People with high blood pressure and cholesterol, who smoke, have diabetes, are overweight or sedentary.

But there's no way to tell when a heart attack is imminent. Tests can spot that an artery is narrowing, or if a heart attack is under way or already has damaged the heart muscle. They can't tell if the plaque inside arteries is poised to rupture.

So it's not that uncommon for someone to suffer a heart attack shortly after passing a stress test or being told that their chest pain was nothing to worry about.

Wednesday's study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, investigated cells shed from the endothelium, or the lining of blood vessels, into the bloodstream. They're called "circulating endothelial cells."

First, Topol's team paired with Veridex LLC, a Johnson & Johnson unit that makes technology used to find cancer cells floating in blood. Could it find these cardiovascular cells, too?

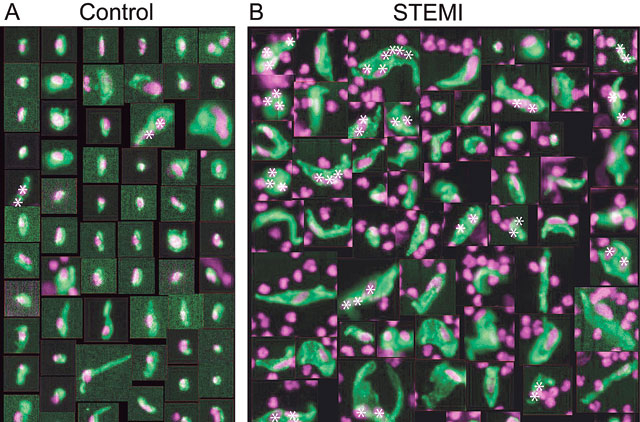

The team took blood samples from 50 heart attack patients - before they had any artery-disturbing tests or treatments - and from 44 healthy volunteers. They counted lots of the endothelial cells floating in the heart attack victims' blood, and very little in the healthy people's blood.

The big surprise: The cells in the heart patients were grossly deformed. "Sick cells," is how Topol describes them.

The study couldn't tell when those abnormal cells first appeared - and that's key, said Wake Forest's Little. It's not clear how many heart attacks happen too suddenly for any warning period.

But Topol theorizes there are plaques that break apart gradually and may shed these cells for up to two weeks before the heart attack. He cites autopsy studies that found people's arteries healed several plaque ruptures before the final one that killed them.

Topol said Scripps and Veridex have filed for a patent for a blood test to detect the abnormal cells.