London: When Argentine forces seized the Falklands 30 years ago, Patrick Watts found himself a first-hand witness to an invasion that caught Britain unawares 12,800 kilometres away.

As the presenter on the radio station in Port Stanley, he was instructed by Governor Rex Hunt to remain on air, broadcasting to a shocked population, for as long as possible. He fulfilled the mission until the new military rulers marched into the station with a series of taped edicts to play to the islanders.

So Watts and his fellow Falklanders were delighted last week when David Cameron responded to months of increased posturing and bullying by Buenos Aires with an uncompromising denunciation of Argentina's motives.

Even as the deepening war of words seemed to raise the spectre of a fresh showdown in the South Atlantic, the mood was buoyed in the small capital of brightly-coloured homes.

"Everyone here was very heartened by this show of support from London and relieved that Britain hasn't forgotten the incredible sacrifices of 30 years ago," he said. "The Argentine threats brought back very unwelcome memories of 1982 for us here, and so we felt very reassured by Mr Cameron's comments."

If Watts is anxious to avoid history repeating itself, so too is Adrian Maroni, a haggard-looking Argentine who was among a crowd of Falklands veterans protesting over war pensions last week outside the Casa Rosada, the pink, neoclassical presidential palace in the steamy capital, Buenos Aires.

He lost 649 comrades during the invasion ordered by the country's dictator, General Leopoldo Galtieri, which is widely remembered in Argentina as a reckless gamble to garner patriotic support.

‘Domestic distractions'

While it cemented the reputation of Margaret Thatcher, then facing a tough first term in office, it prompted Galtieri's removal from power just days after the British flag went up again in Port Stanley.

"It's a repeat of what we saw with Galtieri and Thatcher," said Maroni, who, like many veterans, accuses successive Argentine governments of doing little to care for them. "A drunk general and a weak prime minister both needed domestic distractions in 1982."

Yet, despite Argentina now being a democracy rather than ruled by a junta, the question of who should own Las Malvinas, as the Argentines call them, remains an irresistible card for politicians to play.

Three decades on from the conflict, it is the turn of President Cristina Kirchner, the fiesty ex-lawyer who draws inspiration from Argentina's other great female demagogue, the late Eva Peron, to make the 180-year-old dispute a priority again.

In combative interviews with The Sunday Telegraph in Buenos Aires last week, senior figures in her party blithely dismissed the aspirations of the island's residents to remain British, describing them as colonial ‘imports' whose views should count for nothing.

"These people were imported to the islands and cannot be allowed to determine policy," said Daniel Filmus, head of the Senate foreign affairs committee and a leading member of Kirchner's ruling Victory Front alliance. "When we reclaim the islands, we will respect their way of life, but under no circumstances should we be negotiating with them."

Carlos Kunkel, a long-time ally of Kirchner and fellow Peronista in his youth, went even further. In rhetoric that would not have seemed out of place in the Victorian era, he painted London as a flagging colonial power, desperate to keep what remained of its empire.

‘Policy of piracy'

"David Cameron is pursuing a policy of piracy and aggression because at home the economy is collapsing, there are riots in London, and Scotland and Wales want to escape the English empire," he claimed. "The islanders are a transplanted people who live in an occupied British enclave. You cannot talk about self-determination in those circumstances."

Last week, Kunkel's accusations were fired back across the Atlantic by Cameron, who retorted that it was Buenos Aires that was guilty of ‘colonial' ambitions.

Aides pointed out that, as a land settled mainly by Spanish settlers, Argentina was in no position to lecture on colonial injustices. "The definition of colonialism is to look at some land and say, ‘We want it', whatever the inhabitants think," said one senior British diplomat. "That's Argentina's policy on the Falklands. We know about colonialism, and it's they who are the ones with colonial attitude." The trenchant British position was backed by Mike Summers, a member of the islands' legislative assembly, whose grandchildren are eighth-generation Falklanders. "The reality is that 90-plus per cent of the inhabitants of North and South America and the Caribbean are settlers or descendants from settlers, as are New Zealand and Australia," he said. "The Falklands is no different."

Upsurge in rhetoric

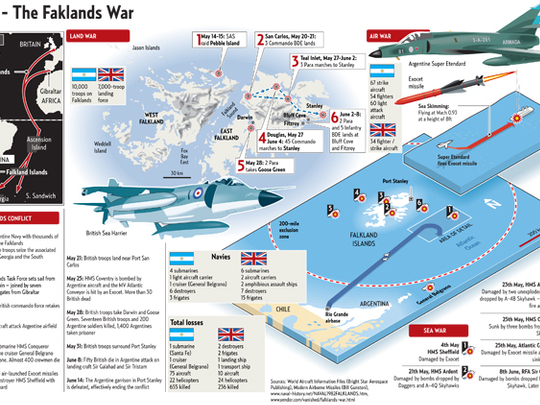

This was always going to be a high-profile year for the islands, a windswept South Atlantic archipelago that many Britons knew little of until the time came to defend them. April 2 is the 30th anniversary of the invasion, which claimed 258 British lives. And next month, the Duke of Cambridge arrives for a six-week tour of duty as a helicopter pilot with an RAF search-and-rescue team.

But the anniversary is also a chance for an upsurge in rhetoric from Kirchner's government, which has denounced Prince William's deployment as a deliberate provocation. No matter however far-fetched the prospect of success, she remains determined to pursue Argentinian ownership — not least because it was also a goal of her husband and predecessor as head of state, Nestor Kirchner, who died of a heart attack in 2010.

Nor are such ambitions purely the preserve of jingoistic Argentine politicians. Across the political spectrum, there is consensus that the ‘Malvinas' are Argentine — a principle drummed into children from their first year at school. That claim is based on a contentious interpretation of the islands' history during the colonial era, when Spanish, British, French and Argentine trading posts frequently switched hands or were simply abandoned.

Perhaps the only thing that is not in dispute is that they have been in British hands since 1833. These days, however, more than just national pride is at stake.

In recent years, prospectors have begun tapping into what are believed to be substantial oil fields in Falklands' waters, and, while exploration is still in its early stages, it is thought that they could contain 8.3 billion barrels, almost two-thirds of what remains in the North Sea. And the more the oil starts to flow, the angrier Buenos Aires is likely to get. True, nobody sees war as a realistic prospect again — not least because, today, the archipelago is one of the most heavily defended pieces of turf in the world.

Dispute showing no signs of dying down

It is believed that the events that transpired leading to the Falklands war between Britain and Argentina 30 years ago may repeat itself. Months of posturing by Buenos Aires have been met with a snub by British Prime Minister David Cameron, leading to relief among the English population who have settled there. There is, however, speculation that a showdown may not have been avoided yet.

Margaret Thatcher Her popularity waned amid recession and high unemployment, until economic recovery and the 1982 Falklands War brought a resurgence of support resulting in her re-election in 1983.

Leopoldo Galtieri Under dictator Galtieri, Argentine forces invaded Falkland Islands. Falklands capital Port Stanley was retaken by British forces in 1982, and Galtieri was removed from power.

David Cameron The British Prime Minister told members of parliament in the House of Commons that Argentina had a ‘colonialist' attitude towards the islands, and urged for a peaceful settlement.

Cristina Kirchner Argentine President criticised Cameron's remarks on the recent standoff on the Falklands, and said people only spoke in such a way when they did not have solid arguments to fall back on.