Sahiwal: Pakistani police struggling to stem a growing Islamist insurgency are recruiting traditional village tax collectors to snoop on militant groups — but critics say the plan is ill conceived and unlikely to be of much use.

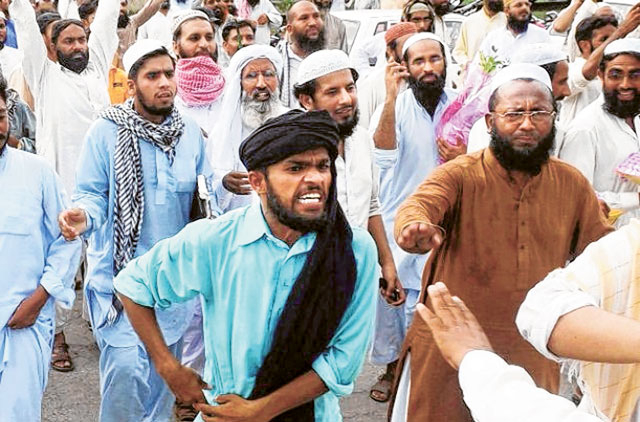

One day recently about 100 of the tax collectors, known as numberdars, sat under a big tent in the town of Sahiwal, in Punjab province, listening to lectures from policemen and lawyers about their new duties.

A police official read instructions from a briefing booklet to the men, many of them wearing turbans and other traditional garb, before the day-long session ended with a question session during which some of the men raised fears for their safety if militants caught on to their spying.

"We asked the government to issue us with arms licences so we can protect ourselves," said one of the men after the session.

"Otherwise we and our families will be at risk of attack," said the would-be informant, who declined to be identified for security reasons.

Violence has surged in Pakistan since a 2007 government crackdown on militants who had long been tolerated, and even nurtured, for use as tools against old rival India.

Now authorities are turning to any means they can to try and end the bloodshed and police in Punjab hope the force of collectors of taxes on water for irrigation, first set up under British colonial rule, can augment their efforts.

Eyes and ears

"We want numberdars to become the eyes and ears of police and help us in eliminating terrorism," senior Sahiwal police official Shahzada Ghous Ahmad, who is organising the workshops, said.

The plan is being field tested in Sahiwal, 340km south of Islamabad, and about 800 numberdars have been trained since the beginning of June.

During the workshops, the numberdars are given a booklet containing the names of 32 militant organisations, including Al Qaida, the Taliban, Lashkar-e-Taiba and Sipah-e-Sahaba, and asked to provide information about their members.

The Lashkar-e-Taiba is a anti-Indian militant group with historically close ties to Pakistan's top spy agencies. It is accused of being behind the 2008 Mumbai attack that killed 166 people.

Sipah-e-Sahaba is an anti-Shiite organisation allied with the Pakistani Taliban. Its off-shoot, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, is allied with Al Qaida and has killed hundreds of minority Shiites over the years.

"It is now the duty [of the numberdars] to point out religious extremists and those having links with terrorist organisations," police said in the 12-page booklet.

Punjab is Pakistan's biggest province, home to some of its most violent militant groups, and the numberdars are told to get information on their activity.

Security officials in Sahiwal said they had prepared a list of 111 hardcore militants in the district and numberdars have been told to find out what they're up to.

Under the old numberdari system, influential landlords were appointed to collect water taxes for the government and help police control crime.

But the system virtually disappeared after Pakistan's independence in 1947 when the government appointed its own officials to collect revenue and strengthened the police.

Elders

The bid to revive the numberdari system in Punjab mirrors government efforts to mobilise ethnic Pashtun elders in the north-west to tackle militancy there.

There some tribal elders have raised militias to help the military but the militants have struck back, killing hundreds of elders and militia members. Security analysts said the numberdars' fears that the same fate could await them were justified.

"The numberdar is part of the society. If he started telling this then he can be killed," said military expert and security analyst Aisha Siddiqa. "Why should he do it?"

Police official Ahmad said they had promised to allow numberdars to keep weapons if they provided good information about militants.

Another analyst said the plan had not been properly thought through.

"It's a half-hearted and not very well thought out effort because it is risky for those who will do this job and apparently there is no back-up plan to protect them," said political and security analyst Hassan Askari Rizvi.

For years, the militant groups have been woven into the political fabric of Punjab with provincial governments pandering to the Islamists to drum up electoral support.

Campaign

The Punjab provincial law minister, Rana Sanaullah, last year campaigned openly with the head of Sipah-e-Sahaba and courted the votes of group members and supporters.

Given such long-standing links, authorities didn't need the numberdars to expose the militants' secrets, and the programme was little more than political theatre, said Siddiqa.

"It's a drama. They already have this information," she said. "Historically, we've seen when leaders of banned organisations are arrested then they [government officials] make phone calls for their release."