Ciudad Juarez, Mexico: In a dusty hillside slum, one of Ciudad Juarez's most dangerous, an immaculately refurbished park spreads for two blocks, interrupting the concrete shacks with a brand new covered amphitheatre, Astroturf football field and playground exercise toys designed to fight childhood obesity.

"Todos Somos Juarez" — "We're all Juarez" — is plastered across the maze of slides and swing sets, the name of the Mexican federal government's unprecedented 3.4-billion-peso (Dh1 billion) programme to increase education, jobs and safety in the violence-plagued border city, considered one of the world's most dangerous.

Shortly after the park was inaugurated in September, a dead body was dumped on the basketball court.

"It's nice to have a park," said Teresa Almada, director of Casa de Promocion Juvenil, which runs the youth centre there. "But the issue is, how can people enjoy the park if the bullets are still flying?"

Disenchantment

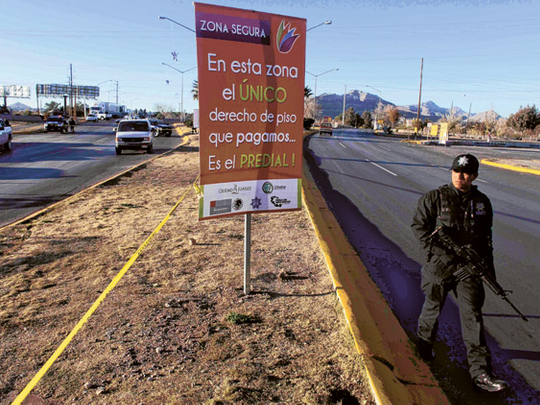

Such are the precarious successes of Todos Somos Juarez, a programme promoted at every turn by President Felipe Calderon to newly elected Mayor Hector Murguia as proof that Mexico is fighting a vicious drug war with more than guns and troops. Investments designed to counter the poverty and disenchantment that supply cartels with foot soldiers are injected throughout the city: parks and new high schools in some of the poorest neighbourhoods, new hospitals and clinics and more police patrols in commercial districts to stop the extortion that has devastated Juarez's local economy.

The task is enormous. Before violence started to escalate in 2008, the result of a war between two cartels to control the city's lucrative drug trade, Juarez suffered for decades from lack of investment from the state and federal governments. For every high school built under Todos Somos Juarez, the city is short another. Residents distrust government authorities, who in the past seemed to be working for the crime organizations they were supposed to be fighting.

Now the drug war has caused thousands to flee. The stepped-up patrols came after the city's once-thriving commercial strips had been reduced to rows of decrepit, boarded-up buildings. Even with new medical facilities, doctors have closed private practices and staged walkouts to protest kidnappings.

Since Calderon personally launched Todos Somos Juarez in February, forming community round tables of academics, civic groups and business leaders to vet projects and track their progress, the city has experienced its most violent year _ topping 3,000 murders by mid-December.

"We're very sceptical," said Dr Leticia Chavarria, a member of the Citizens Medical Committee who sits on the security round table. "In the months since President Calderon came and formed the working groups ... crime went up, despite thousands of police in the city."

Slow changes

Calderon counters that social and economic development don't produce results overnight. His government has studied Colombia and Palermo, Italy, other places infamous for their dominance by organised crime, and both turned around over periods of years.

"If we're building five high schools or three more universities, don't tell me it's not working when classes just started a month ago," Calderon said in an October interview with The Associated Press. "We need to have several generations with educational opportunities. We need to reintegrate these new generations of students into the productive structure of Juarez. It is long-term work."

As in many parts of Mexico, drug trafficking was an accepted part of the economy as long as things stayed relatively quiet. That started to change with the border clampdown after Sept. 11, 2001, that pushed drugs intended for the US into the local streets.