Whether it is taking photos inside Giza's Pyramids, taking skull or bone memorabilia from Paris's catacombs or wandering freely around Machu Picchu, tourists have to be banned from doing certain things lest they cause too much damage. Rules contain the fun, and by consequence, help the environment.

A set of boring do's and don'ts on a white beach fringed with coconut palms seems the last thing you want to hear when looking to kick back. But on Sipadan, a tropical island off the northeastern coast of Sabah, Malaysia, the little book of management rules has raised it to one of the most exclusive diving destinations in the world.

Sipadan once was, and is becoming again, an emerald jewel with treasures beneath its azure waters. At present, only 120 people are allowed to dive around the island on a daily basis — a far cry from the free-for-all destination it was almost 30 years ago, which caused its environmental demise.

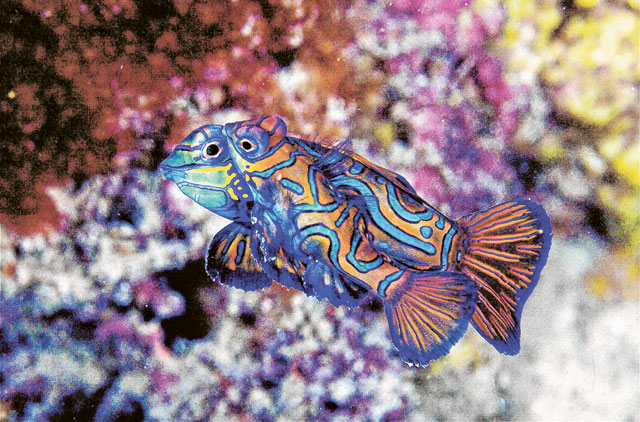

Colourful ecosystem

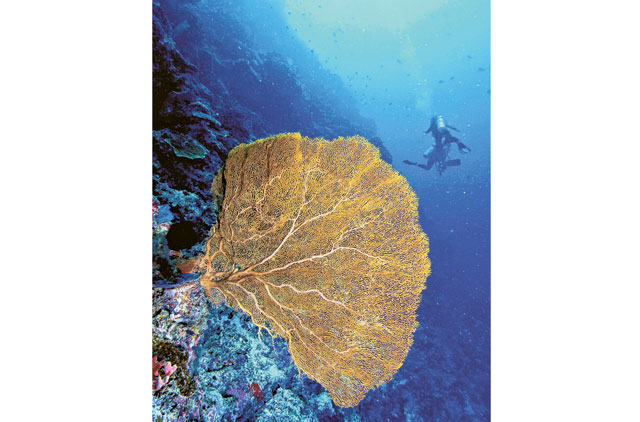

Located in the Celebes Sea of the Western Pacific Ocean, Sipadan was formed from living corals growing on top of an extinct underwater volcanic cone, and rises 600 metres from the seabed.

More than 3,000 species of fish and hundreds of coral species have been classified in its ecosystem. Sharks and turtles congregate to the reefs and coral drop-offs, where on any given day divers are treated to scenes of big bumphead parrotfish trawling the shallows; and shoals of jackfish, brightly coloured yellow fusiliers and barracudas will encircle you at a moment's notice, vanishing just as fast as they had appeared.

Forty minutes away by speedboat, the nearby island of Mabul serves as the headquarters for divers who have been anxious to dive into this underwater shangri-la since the six resorts previously on Sipadan were closed down by the government in 2004. The move came amid environmental reports of degradation on and around the island, smaller shoals of fish, bad water quality due to inadequate sewage treatment and an uncapped number of visitors.

"It wasn't sustainable," said Clement Lee, 59, owner of Borneo Divers Resort Mabul and a Sabah Tourism board member. Lee has been diving Sipadan for 28 years and is largely credited for opening up diving there to paying tourists.

In 1983 he discovered how amazing Sipadan was. By 1984, together with three business partners, Lee had set up the first diving "resort". "In Sipadan, before we started this commercially, when we put our heads in the water, goodness me, I think everybody agreed that this island, at that point in time, was our future," Lee said.

"The marine life was superb. We were in Sipadan, there was nobody in Mabul. We were the pioneers, so to speak, pioneers in introducing the certification [Professional Association of Diving Instructors, or PADI] and we were also pioneers in the development of Sipadan island," Lee added.

Everything had to be brought in by ship to the remote island, including tents, cooking instruments, food and water. "It was a tedious procedure. I must say it was tough. All four of us [business partners] were working very hard to make it work. We knew what diving tourism was, but it was a process to reach there," Lee said.

Destinations such as the Maldives or the Fiji Islands had already been established as reputable diving locations. Sipadan was unheard of and harboured some of the most untouched coral reefs in the world.

"We saw so much stuff that is beyond incredible. The marine life was ten times what you see today, with turtles flying, zooming everywhere; fish criss-crossing, and big stuff coming to the surface, such as hammerheads, at 20 metres," Lee said.

"We knew there was an industry. We just wanted to know how to get there. We were confident that if we worked very hard, our focus would produce results," he said.

Aside from attracting holidaymakers, Sipadan is a stopover point for migratory birds and was originally declared a bird sanctuary in 1933. It was declared a nature reserve in 1981, but in 1997, after environmentalists raised the red flag, the Malaysian government announced restrictions on the number of tourists.

Resorts started sprouting on Sipadan and wooden structures often emerged on the beach. At high tide the water would come up to the steps of the restaurants.

One of the most famous visitors was the French marine biologist and filmmaker Jacques Cousteau in the mid-1980s. His ship, The Calypso, came upon the island almost by accident while researching sperm whales. While he was not on board at the time, Cousteau's crew urged him to see for himself what they had discovered.

"I understand that at that time he was having lunch with president Ronald Reagan. He flew over and we met him afterwards. He famously said, ‘I've seen places such as Sipadan island before, some 45 years ago. Now we've found again an untouched piece of art,'" Lee said. Cousteau went on to make a documentary called Borneo: The Ghost of the Sea Turtle, which propelled the island to international prominence.

Nonetheless, by 2003 the authorities declared that all Sipadan's hotels must vacate by January 1, 2005. E. coli had affected the water quality, marine life had depleted and corals were being damaged on a daily basis. Those who could afford it left and set up secondary dive resorts on Mabul, Kapalai or Sempurna.

"Borneo Divers was the first to stand up and say, ‘Yes, we will leave.' We were followed by another resort. At that time if we had not left, nobody would. To my mind, the island would not have been able to withstand any more of the onslaught on its environment. I saw the declining situation. By 2004 it had hit rock bottom," Lee said.

The uncontrolled number of divers meant there was between 200 and 300 divers every day, besides 200 to 300 resort staff, all having a huge impact on the ecosystem.

The four remaining resorts formed a consortium in a bid to be allowed to remain on the island and offered the government an alternative conservation proposal, but it was refused. Finally, after several extensions everybody had left by February 28, 2005.

UAE resident Simone Caprodossi, from Italy, an underwater photographer from the Emirates Diving Association who has dived more than 400 times, recently returned from Sipadan. His first visit dates back six years, when he stayed on Mabul island. "They had not yet established the permit system and Sipadan could be dived daily. I had amazing memories of that trip and I wondered if it would impress me as much this time. But it was well beyond what I remembered! Sipadan fully lived up to the memories, with turtles coming out of everywhere and sharks, barracudas, jacks in great numbers, and a gorgeous reef. It is rare to find a very renowned diving destination kept so well," he said.

"The introduction of permits is necessary and more destinations in the world should be as wise as the Malaysian authorities. As a diver you are aware of the impact you have on the marine environment, as careful as you may be. It makes sense to limit the number of people to preserve an environment such as Sipadan's. It also makes the day there feel more special and you try to treasure every minute," Caprodossi said.

Professional standards stressed

Borneo Divers Mabul Resort established a training institute to put qualified divers in the water based on the principles of PADI. The diver centre was trained to Dive Master level and higher, and the institute was open to staff from other resorts as well.

"The two basic principles in the development of the company is environment and development of human resources. We believe the diving industry is a dedicated one and should be handled by professionally qualified people," Lee said. "There are more dive resorts coming up and it's vital that we are all of a professional standard."

Lee says he can see a lot of positive changes taking place. There are more sharks, more turtles — particularly small ones, which is an indication of healthy marine life. "The coral reef at 5 metres has regenerated so well. It is amazing how quickly nature grows back if you allow it to go undisturbed for a while. This island is out of bounds from 6pm to 6am and that is already 12 hours for the marine life to be resting, and it's doing them a lot of good."