Inside world’s biggest sperm bank

Sperm bank exports to more than 70 countries, and is responsible for more than 2,000 babies a year

Denmark: Ole Schou was 27 years old when he had a dream. It was 1981 and he was a graduate student at a business school in the Danish city of Aarhus.

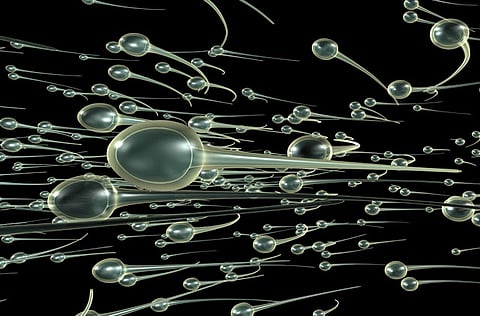

In the dream, Schou saw an icy blue sea and, caught in the waves, hundreds of frozen sperm. “It was such a peculiar dream that I could not forget it,” he recalls, “so sometime later I walked into the university library and asked for any literature on sperm and fertility.”

Schou started reading and became obsessed. “My dream had given me another dream,” Schou says. “I was going to build a sperm bank.”

That dream came true. Cryos, the company Schou started up 25 years ago this month, is today the world’s largest sperm bank. Schou estimates that Cryos has been responsible for more than 30,000 births, producing more than 2,000 babies a year, and in what has been called a new Viking invasion the company exports sperm to more than 70 countries. Cryos and similar companies, such as the European Sperm Bank, have helped turn Denmark into the sperm capital of the world.

Cryos operates from the fifth floor of a redbrick building in the centre of Aarhus, Denmark’s second largest city. It is here that sperm is donated, analysed, studied and finally dispatched to clinics around the world.

Hanging in the reception area is a large blue painting inspired by Schou’s sperm dream. The walls of the corridors are lined with large photographs of smiling babies and magnified images of sperm. To the right of the reception are three brightly lit rooms.

“The men can look at a magazine, watch a film or listen to music,” Schou says. As we are talking, a young man in a green hooded jacket arrives at reception. He walks into a cabin and shuts the door behind him. A red light flashes on. “The majority of donors come once or twice a week,” Schou says.

The Danish laws on donation have recently been tightened after a donor at a rival sperm bank was found to have passed on a rare genetic condition to at least five of the 43 babies he is thought to have fathered. New potential donors are interviewed, their health evaluated and checks made regarding any history of disease in their family.

Cryos attracted headlines last year for announcing that red-headed men would not be able to donate, as there was insufficient demand for ginger babies. The truth, Schou told me, was the bank already had plentiful supplies of sperm from redheads and could afford to be picky about new donors.

“When I started out back in the 80s, it was not easy to get men to donate,” Schou says. “I would ride my bicycle carrying printed sheets of A4 paper that said ‘Become a donor and help childless women’ and people would look at me very strangely. I remember one time I was in a restaurant toilet and I saw a beautiful black man. At the time it was hard to get sperm from men of different ethnicities, so I told him I was in need of sperm. He became very angry and punched me.”

Schou no longer needs to advertise: Cryos has a bank of 170 litres of sperm and a waiting list of 600 donors. The reasons for wanting to donate, he says, are not just financial: donors receive around 500 kroner (54) a time, but when the rate was at one point increased, the number of donors did not change.

Rather, men are driven by a mix of altruism and a desire to earn “pocket money” many are students at the university nearby, for whom sperm donation has become almost a rite of passage.

The young man steps out of the cabin and hands over a cardboard kidney-shaped tray. The sperm is left to settle for 30 minutes before a lab technician takes a sample and studies it under a microscope, measuring its health and speed. “Good sperm quality is genetics,” Schou explains.

Freezing agent is added to the sperm to dehydrate it, before it is sucked into a straw; a single donation can produce anything from one to 20 straws, but five is typical. The straw is then labelled and heat-sealed before being frozen in avapour of liquid nitrogen and, finally, deposited in a large grey metal tank of liquid nitrogen where it is stored at a temperature of -196 Celsius.

Schou slowly lifts the lid from one of the tanks. He tells me they have around 130,000 sperm samples. In the room next to the tanks stands a pile of metal containers, holding sperm ready to be sent to fertility clinics in Ireland, Germany, the Netherlands, Pakistan and Britain.

It was one such straw of sperm from Cryos that gave Mary, from Edinburgh, the chance to have a baby. The 32-year-old teacher had been trying to get pregnant for six months. Tests revealed there was an issue with her husband’s sperm and the couple decided to contact their local fertility clinic. But, she discovered, “British sperm was not readily available. There just wasn’t enough choice.”

According to Dr Richard Fleming, the fertility specialist who treated Mary, this is due to changes to the British law on anonymity. “In 2000, the government decided to start a database of sperm donors and that led to a dramatic decline,” he says. “Then in 2005 came the loss of anonymity for donors, meaning that children had the right to contact their donor father when they reached 18. Those two changes stopped men coming.”

Faced with a lack of domestic sperm and unwilling to enter the potential minefield of asking a friend to donate, Mary and her husband decided to use Cryos. They began searching on the company’s website for the right donor. The price of sperm ranges from around 30 to 350 a vial depending on whether the donor is anonymous, on whether they have provided an extended profile and on the quality of the sperm.

Donors can include basic details of height and weight alongside baby photographs, an extended personality profile and even recorded messages, where they explain why they have chosen to donate.

“It felt like shopping on Amazon,” Mary says. In the end, she decided on gut instinct. “We chose the donor and clicked to place the sperm in a cart. Once payment was made, we were told it was being flown to our clinic.”

That was five years ago. Today Mary is the mother of two girls both from the same donor and only her immediate family know the truth. “It’s hilarious almost every day we are told one of our daughters is the spit of her dad. I guess people see what they want to see.”

One day, Mary plans to tell her girls the full story: “Evidence suggests that donor-conceived children do best when told from an early age.”

“If I can help someone to achieve their dream of having children, then I would like to do it,” says Kristian, a 25-year-old engineering student from the north of Denmark who has been donating sperm once a week for two years. “I believe in karma, and I come from a broken home. I think if you have considered having a child enough that you’re contemplating insemination, then you have put more thought into it than most parents.”

Unlike Britain, Denmark allows anonymous donation and as with around three-quarters of Cryos’s donors Kristian is anonymous; any children he has will have no way of being able to identify him as their biological father.

With non-anonymous donors, the woman receiving the sperm will not know the identity of the donor, but any child would, at the age of 18, have the right to find it out. A British woman who imports sperm from Cryos has to choose anonymous donor, as the donation would be subject to the regulations of the UK’s Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, but if she chose to travel to Denmark, she could opt for an anonymous donor.

The possibility of anonymity is one of the reasons Denmark attracts so many donors, Schou believes, and why its sperm is so popular around the world. “Also, we are a pretty liberal country,” he says. “We don’t have many religious complications and we are not so stressed by sex, but also we are a small country and so we are used to thinking about each other’s welfare.”

It doesn’t hurt that so many of the Danish donors are tall, fit, athletic young men. Lucas, 19, is blond-haired and blue-eyed, with a square jaw and wide smile that makes him look like a young Matt Damon.

He plays football and lifts weights when not studying law. Lucas donates once a week and has given an extended profile online with childhood photographs and a statement about why he has chosen to donate. “I would be happy if any baby that is mine contacted me when they were 18,” he says, “because by then I would be 40.”

Not all donors are so relaxed about the prospect of meeting their children. Pierre is a 21-year-old student in European studies. He was born in France but is now living in Aarhus and has been donating sperm three times a week for the past month.

“It’s a way of helping people, like giving an organ when you are dead, and I also make some money,” he says. He is an anonymous donor who has given information only about weight, hair and eye colour: “I want to be of help but I don’t want people to buy some part of me.”

It was his girlfriend who suggested the sperm clinic to Pierre and, after our conversation, I spot him trying to persuade the lab technicians to allow her into the cabin with him next time. The request is firmly declined.

Simon, 24, has receding sandy hair and a goatee. “I moved to Aarhus four years ago and I couldn’t find a job,” he says. “I didn’t have any money, but I had an apartment I couldn’t afford and that was how I came to be a donor.” Simon would sometimes visit Cryos five days a week, but he has now cut it down to twice-weekly.

Simon earns around 2000 kroner a month and he uses the money to buy treats such as an Xbox. The average donor at Cryos can assume he has fathered 25 children, but Simon is likely to have more than 100 offspring.

“The only time I think about it is when I worry that my anonymity will be taken away,” he says. “If politicians changed the law, suddenly all these children would be streaming to my door, wanting their father back. That would be horrible.” He adds: “My parents don’t know I do this. My mother would find it hard to know she had grandchildren she would never meet that would upset her.”

When Cryos began, in 1987, their clients were mostly women like Mary whose husbands had fertility issues and men who had been diagnosed with cancer and wanted to store their sperm before it was damaged by chemotherapy.

“The profile has changed dramatically over the past few decades,” Schou says. “The women are getting older, and during the past few years we have seen two new types of client: lesbian couples and single females. Forty per cent of demand is now coming from single women. These are highly educated, economically successful women who have focused on their career but now the biological clock is ticking and they have to do something.”

At 41, Ellie was single and felt she was running out of time. She didn’t have any single male friends she felt comfortable asking for sperm and she didn’t want to take the risk of having a one-night stand.

Ellie bought three vials of sperm from the Cryos website, delivered to a clinic in London where the insemination took place. Ellie now has a daughter and is already thinking of having another baby by the same donor.

Everyone except her direct family and very close friends believes the child is the product of a relationship that did not work out. “I’m grateful to the sperm donor, but he isn’t really a person to me,” she says. “I have no concept of who he is or even if my daughter looks like him. If I could say one thing to him, I would say thank you.”

Schou, now 58, has a new dream. Cryos currently has the office in Aarhus, three sperm collection centres in Denmark and a small presence in New York. The new phase of the Viking invasion will see Cryos going international.

“The trouble with Danish sperm is that there is very little diversity,” Schou says. “The donors are almost all white and blond with blue eyes. If we want to help women in different parts of the world, we need to be able to access non-Danish sperm.”

Schou wants to set up sperm banks in Spain, South Africa and India. It is a grand and potentially lucrative vision, but at its heart it is the same dream Schou had 25 years ago when he started Cryos.

“In the end,” he says, “I am simply the middleman, between the young men who want to donate sperm here and the women out there who want to have babies.”

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox