Moscow: Half a century ago, a Russian carpenter's son named Yuri Gagarin became the first man in space, carving an indelible mark in human history and scoring the greatest Soviet Cold War success.

The 27-year-old's 108-minute flight on April 12, 1961 is still remembered in Russia, even after the collapse of the Soviet Union, as its greatest national achievement. His death in a plane crash seven years later only added to his mythical status.

Gagarin's safe return to earth in central Russia, where he was famously given bread and milk by an astonished grandmother, ensured he would live the rest of his life as a legend in Russia and abroad.

Hundreds of thousands flooded the streets of Moscow when news broke of his triumph, which confirmed the Soviet Union's undisputed supremacy in the space race, a lead it would keep for eight years until Americans walked on the moon.

The other-worldly allure of Gagarin is exemplified by the 40-metre-high titanium monument that still bears down on Moscow, his arms outstretched like a bionic superman and apparently preparing to shoot upwards into the sky.

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev seized on the propaganda value of Gagarin's coup in beating the United States into space, sending him on "missions of peace" around the world, to meet figures including the Britsh Queen.

"This achievement exemplifies the genius of the Soviet people and the strong force of socialism," the Kremlin crowed in a statement at the time.

The US could only respond more modestly, putting Alan Shepherd into a short sub-orbital flight on May 5, 1961. The first US orbital flight by John Glenn came almost one year after Gagarin on February 20, 1962.

Great power

Russia's modern day leaders are also not expected to shy away from using the anniversary on Tuesday to remind Russians and the world of its past achievements and that it remains a great power on the global stage.

Gagarin was confirmed as pilot just four days before launch, a choice which propelled him to stardom and the reserve Gherman Titov, who would later become the second Soviet cosmonaut in space, to relative obscurity.

His name also overshadows the mastermind of the mission, Sergei Korolev, who designed the equipment that took Gagarin to space yet whose role in the space programme was kept a state secret until his death in 1966.

An extraordinary figure, Korolev survived imprisonment in the gulag in the Stalin purges to work tirelessly on the space programme. He died while working on a massive rocket, the N1, which he hoped would take Soviets to the moon.

When Gagarin was killed, a driving licence, 40 roubles and a photograph of Korolev were found in his pocket. Few lives in modern history have been the subject of so much mythologising as that of Gagarin, with every aspect of his mission and subsequent life pored over in detail.

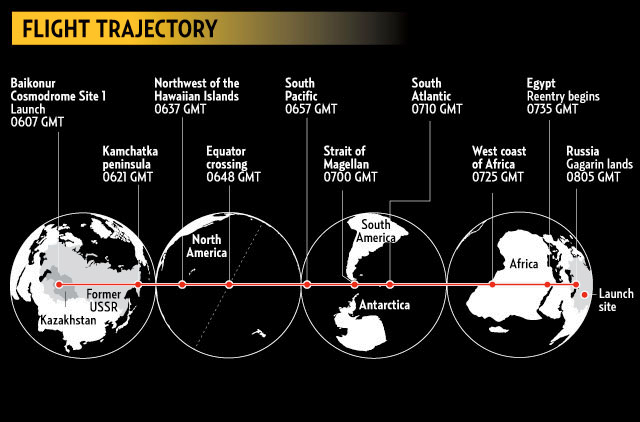

He took off at 9.07am Moscow time from the Baikonur cosmodrome whose location in the south of Kazakhstan was tightly kept secret.

He ejected and parachuted down to earth in the Saratov region of central Russia. The first people to make contact with the cosmonaut were peasant Anna Takhtarova and her four-year-old granddaughter Margarita.

"I looked round and saw this orange monster with a huge head coming towards us," Margarita recalled in an interview with tabloid daily Komsomolskaya Pravda. "Grandma helped Yuri Gagarin take off his helmet — she pressed some kind of button. And when we saw a smiling face in front of us we understood that it was a human being in front of us."

The deaths of Korolev and Gagarin coincided with the end of the Soviet Union's lead in the space race that started with the launch of the first orbiting satellite into space, Sputnik-1 in 1957.