Premvati Devi slowly turns the pages of her family photo album. Her eyes fill with tears as she looks longingly at the smiling face of her four-year-old son Premjot Singh who went missing from outside their home in Delhi last August. She and her husband Sobhraj have not heard any news of him since. “I still cannot believe it,’’ says Premvati, 42, hugging the album close to her chest and kissing her son’s picture. “He was so innocent.

Our everything. We’ve lost him forever. We’ve tried everything to find him but he’s gone.’’ Their elder son, Pritam, 12, who is sitting next to her, looks away uneasily. Premvati turns and kisses his cheek. “He is the only one we have now,’’ she says. “And we will not let him out of our sight.’’ Premvati remembers that late August afternoon like it was yesterday.

“It was a Sunday and Premjot and I had just finished our lunch when he ran out to sit on the steps to look at the vehicles driving down the road in front of our house. Pritam had gone out to play with his friends. “Just ten minutes later, I popped my head out to check on Premjot and he wasn’t there,’’ Premvati recalls, panic and desperation still ringing in her voice. “I stepped out and began calling out to him... but nothing. An hour passed and still I couldn’t find him.’’

Eventually, Premvati accepted something serious may have happened and telephoned her husband – a tailor with a tenting firm – and told him to rush home. Even before he arrived, Premvati’s neighbours and friends had launched a search for the little boy, scouring the roads and the small park close to their house.

“The nearby railway station, hospitals... we looked everywhere but couldn’t find little Premjot,’’ she says, tightly squeezing her husband’s hand. “I’m sure he didn’t just wander off. He was a good boy and never went out without permission. He could only have been abducted.’

'If I were rich, things would be different'

When they finally approached the police after hours of searching came to nothing, the couple were bitterly disappointed by the reaction. “They weren’t even bothered,’’ says Sobhraj, 43. “They filed a kidnapping case and that was it. They didn’t bother to visit my home or seek more details. Maybe if I was a rich man, things would have been different.’’ Statistics for the number of missing children in India vary depending on the source, but they are shocking nonetheless.

India’s National Crime Records Bureau says one child goes missing in India every eight minutes and a Washington Post report says 14 children go missing in Delhi alone each day. Last year, 60,000 children were reported missing and of these more than 22,000 are yet to be traced, a minister told the Rajya Sabha, the Upper House of Parliament, in August. While the eastern Indian state of West Bengal reported the highest number of missing children – 12,000 – the capital, Delhi, reported 5,111 cases coming in third after Madhya Pradesh, which reported 7,797 children missing.

A leading children’s rights group, Bachpan Bachao Andolan, however, puts the figures much higher. According to a report it released late last year, more than 90,000 children are officially reported missing every year in India. The report added that up to ten times that number are trafficked to beg or work on farms, factories and homes. Kidnapping is, by far, the most common crime against children, according to a government report, which came out in September. A total of 33,098 such crimes were registered in 2011, it said.

The Indian media covers the issue of missing children from time to time, and recent footage from surveillance cameras, repeatedly telecast on several national and regional channels, shows infants being brazenly snatched from train and bus stations, sometimes even as their parents sleep right beside them. So a small boy like Premjot, sitting alone outside his home, would have been an easy target for abductors.

Two decades ago, when Sobhraj and his family moved from their hometown in Uttar Pradesh to the capital for better jobs, he dreamt of a bright future. But he now rues making the move. “If we had stayed back, this might not have happened,’’ he says. Although work in the capital had been very good, the loss of his son has left Sobhraj jobless. While he scoured the streets of Delhi for his son, week after week, his work suffered.

“He didn’t bother about his job,’’ says Premvati. “He spent all his waking hours searching for Premjot. The few days that he did go to work, he couldn’t concentrate, so he quit. He now runs a small grocery store from our house to make a living.’’ The disappearance of their youngest son has made the couple even more worried about the safety of Pritam.

“We never leave him alone, taking him and picking him up from school every day, “ Premvati says. “Losing his little brother has robbed him of his childhood. We don’t even allow him to step out of the house alone now. He doesn’t play and always remains under our watch. We know it’s not fair for him, but what else can we do? We can’t run the risk of losing our other son, too.’’

Lost brothers

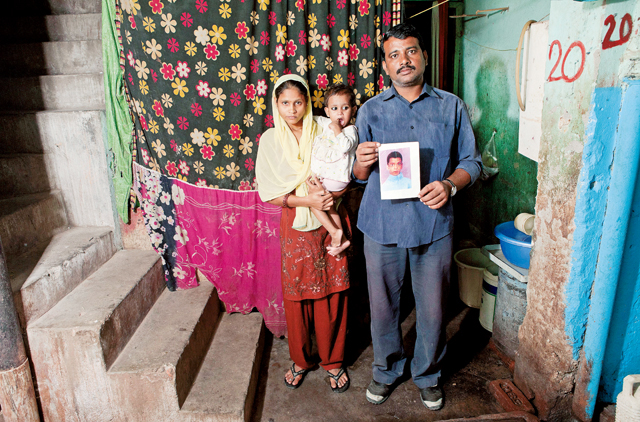

A few miles down the road, Sana Parveen, 34, and her husband Mehtab Ali still grieve for their lost children Feroz Ali and his brother Chotu Ali. Both Feroz, 14, and Chotu, 11, disappeared in 2010. They were last seen playing outside their house in Delhi. Mehtab, 36, who works as a security guard, searched high and low for the pair without luck. He says, “One minute they were playing with a bunch of kids and the next they were gone.’’

Friends told Mehtab that they had seen the boys teasing a truck driver who had parked by the road side. They feared the driver might have abducted the brothers. “We went to several shrines, railway stations and markets looking for them, but there was no trace. I don’t know if they’re alive or dead,’’ Mehtab says. “In some way if they had died it would be easier because at least then I would know what happened to them – there’s an end. But we’re in a never-ending trauma. We have to bear this pain forever,’’ he says.

Again, the police filed a kidnapping case but that was it. “I go to the police station every month, but they tell me there are more important cases to worry about,’’ he says. Investigators say that the absence of photographic evidence makes it nearly impossible to trace the children. Most kidnappers target children between six and 13 years.

Safeguarding vulnerable children

The National Centre for Missing Children says that parents should always have a recent picture of their children. “Trying to trace a child without photographs is extremely difficult,” says V Renganathan, a senior police officer in New Delhi and founder of an initiative called Pehchaan (which means ‘recognition’), where policemen take pictures of children in slums for records and provide copies to their parents. “The idea is to safeguard vulnerable children from poorer neighbourhoods,” he says.

Dina Nath Chauhan, a children’s rights activist, says the police investigations into child disappearances are slow. “I’ve followed many cases over the years and I’ve seen families struggle to file a missing report,’’ he says. Criminals are aware of this, which is why they target children from poor families, he adds. Bhuwan Ribhu, national secretary of Bachpan Bachao Andolan (‘Save the Children’), says, “There are many reasons behind missing children.

It could be a case of kidnapping from a wealthy family for a ransom or forcing children into begging, or to work on farms...Sadly children from socially and economically poorer backgrounds form the majority of victims because very often their parents do not have the means to pursue a case.” Some victims have managed to escape from their captors or have been rescued by the police. Mahinder Singh, 19, is one of the lucky few. He was returning from school in Old Delhi four years go when he was abducted and forced to work on a field in a remote village in Haryana.

“I was walking on the road when some men dragged me into a car and took me

away,’’ he recalls. “There were three other children too; we were all forced to work on the landowner’s field.’’ Eventually, Mahinder saw an opportunity to escape. “I begged with the kidnapper’s father, an elderly man to allow me to go. He was a nice man and he told me ‘OK, go,’ and I ran away.’’ After riding on buses and trucks Mahinder managed to return home and into the arms of his mother Shamkala Devi, 42, who still cannot believe her good fortune.

“It’s been four years and I had no hope of finding him. But now my joy cannot be expressed,’’ she says. Mahinder, too, cannot believe it. “I know so many kids never return home, so I am so very thankful to see my mother again,’’ he says. Premjot’s mother Premvati is still hoping for the day when her son will return. “I can’t bear it; some days I just cry all day worrying about how he is. It’s terrifying. These kidnappers need to be stopped, they need to be beaten up so our children can grow up in safety.”