“Have any new books with art plates come in?” asks a middle-aged guy in a corduroy jacket. Indraneel Mondol takes about a minute to fish out books and art magazines from the stack of books on the pavement that is his shop. The corduroyed gentleman gets busy poring over them. A woman walks up and asks for “Class 7 science books for ICSE board”, which are duly supplied. I have, meanwhile, discovered a pile of old books by grammar police stalwarts such as J.C. Nesfield. I am trying to decide between a 1963 edition of Book IV in his English Grammar Series and a Godard screenplay when an old gentleman asks Mondol for a “western”.

“Louis L’Amour?” asks Mondol, the stall owner, who seems to be an authority on all genres.

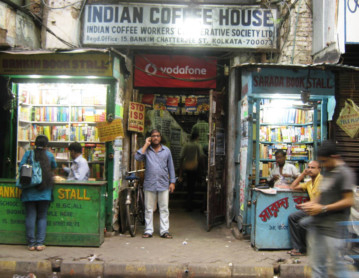

I manage to haggle the damage for my Nesfield book down to Rs100 (Dh6), and look around to see if anyone else has struck a deal yet. It turns out that the corduroy fellow is an arts teacher in the United Kingdom. The old gent is ex-UN, retired. Both love pottering around the secondhand booksellers pavement stalls in Golpark, one of the three main areas in Kolkata where one can find hard-to-get or rare books at a steal.

We all agree that there is probably no better way to spend a wintry morning than here, browsing through books, close to shacks selling hot mugs of tea.

Conversation eventually turns to the upcoming Kolkata Book Fair or the Boi Mela, to be held from January 28 to February 8. The Boi Mela is a phenomenon with huge crowds (around 1.5 million footfalls) and sales (in the region of Rs18 crore), music, author meets, discussions, art and food. The book fair began in 1976 and is a must-visit for Bengalis who claim to be literary. A common conversation starter for Bengalis through end January and all February, and probably March, is “What did you buy at the Boi Mela?”

Boi Mela apart, Kolkata is in right now in the throes of literary fever. The Apeejay Kolkata Literary Festival (APKLF) just wrapped up 28 sessions over five days (from January 14) with Indian writers, Swedish crime writers, Australian indigenous writers et al. The Kolkata Literary Meet (KLM) begins on January 23 and has got itself a plum sponsor this year in Tata Steel.

The fest has lined up a smorgasbord of events for booklovers — Amitav Ghosh, who will talk about the last book in his “Ibis” trilogy; half-Welsh half-Egyptian Shereen Al Feki whose book “Sex and the Citadel: Intimate Life in a Changing Arab World” has earned nominations for the Guardian First Book Award and The Orwell Prize; Joanna Rakoff, best known for her memoir “My Salinger Year”; Aliette Armel, biographer of the renowned French writer Marguerite Duras...

“The response has been huge,” says Malavika Banerjee, the brains behind KLM who gets suggestions for the fest on Facebook all through the year. “I am happy that the city feels so invested in my festival. People have a sense of ownership”.

But this is only half the story.

The fairs and lit fests are just one aspect of Kolkata’s love affair with books. Kolkata, or Bengal, has a rich history of the written word. The book “Printing in Calcutta to 1800: a description and checklist of printing in late 18th-century Calcutta” by Graham Shaw, Head of Asia, Pacific and Africa Collections at the British Library, states that the city became a hub of commercial and government printing in the 18th century as the East India Company introduced printing to facilitate trade and to consolidate the empire. The first to come hot off presses were (mostly) almanacs, calendars, maps, and treatises on medicine, law and land revenue, and lists of its employees and of European residents in the city who were not under its employ.

Calcutta/Kolkata wasn’t the only place from which books were published in Bengal. “In fact, the first book which featured Bengali was printed from Hooghly, by Nathaniel Halhed in 1778,” says Aritra Chakraborti, who has worked on a project on Kolkata’s street literature (choti boi)for Jadavpur University’s School of Cultural Texts and Records’ (SCTR).

“The first book printed completely in Bengali was published from Serampore. Throughout 19th century books of various kinds, from the humblest street literature to sophisticated humanistic publications arrived from various places outside Calcutta. This illustrates how layered the history of printing in Bengal was, and how the industry soon spread to all parts of the state”.

Chakraborti clarifies, however, that printing in Bengal began after printing had started in other parts of India. The first printing press was established in Goa and later it spread to other parts of South India. The first books in Tamil were printed in the 17th century. However, he says, the history of printing in these states remains relatively untold for reasons that book historians cannot fathom.

In search of the iron horse

Areas such as Chitpur Road in north Kolkata housed most of Kolkata’s printing industry. With the advent of new technologies, the traditional methods of manual printing have more or less disappeared. I have heard of a printing press owner who still uses the old letterpress technology. I walk through narrow by lanes in Kumartuli, off the Shobhabazaar crossing in old Kolkata. A tram chugs past. Kumartuli’s lanes are clogged with hundreds of buxom clay idols for the upcoming festival celebrating Saraswati, the goddess of learning. I ask a fruitseller about the letterpress.

You mean Bishuda’s press, he asks? I am guided to a small room, where a smiling bespectacled man greets me. This is Bishwanath Bag, or Bishuda as his neighbourhood knows him. He operates from an unassuming, small shed-like place, with no signage outside. The room has been divided by a roughshod cement partition into two spaces — ground floor and an upper space. As a result ceilings of both the rooms are so low, you have to constantly watch your head.

The two letterpress machines are on the ground floor, along with the wooden blocks set with metal type that are used for confectionery boxes and menu cards. The space upstairs is accessed through a small wooden ladder tied to a hook on the wall with a rope. It is a tiny room where thousands of type is packed like sardines in plastic bags, and inside stack upon stack of wooden slabs with partitions all brimming over with type — alphabets in English, Hindi and Bengali, as well as numbers. Bag’s equipment includes lead type pieces and wood type pieces of different typefaces, which he arranges using a stick.

Letterpress dates back to Johannes Gutenberg and Bag is one of the few surviving members of this age-old tradition. Composing a page takes skill, precision and patience. Every letter in a line of text is set by hand on a plate. Paper is fed into the machine, the plate rolls over ink and transfers the type on to the paper.

Bag takes out type and a wooden frame, and holds a demo of sorts for me. His hands move lightning fast through the process — setting letters in reverse, from left to right in the frame, the remaining space filled out with “space fillers” — pieces that keep the letters and lines in place. Precision is required to make sure the spacing between letters and words, and alignment is all correct. What he composes is the menu for a wedding. Much of the work done on Bag’s letterpress machines comprises wedding cards and menus, bills and memos for small businesses, and some pamphlets.

More interesting is the revelation that the ubiquitous white cardboard boxes with decorative logos used by some of Kolkata’s old confectioners are done at his letterpress. His letterpress stamp can also be found on the bottom panel of boxes of some old and still-popular brands of genjis (undershirts) worn by men here.

It takes Bag about two hours to set and compose 40-odd lines on an A4 size page. For the work, he charges Rs250 per page. “No one has the patience required for these machines anymore,” he says. “Offset, DTP are so much faster — I could have done the same work in half an hour.”

There was a time when Bag’s area had 30-40 letterpress operators. He also has an offset machine and it is run by someone he has employed. “But I like using the letterpress — the skills I learnt are put to good use.”

No one makes the machines anymore. Old machines are sold at the price of iron to scrap buyers — by the kilo. “I sold a machine from Holland for Rs60,000. It was a Mercedes machine, you can’t get them now.”

At the moment, he has got one letterpress job that he is excited about.

“A man from Australia had come,” he says. “He asked him to do a sample page on letterpress, to see my work. He liked what he saw and decided to bring out a book that will showcase the art and history of letterpress printing.

Bag takes out some handmade paper from a brown envelope. They all have the same body of text printed on them — “These are sample pages the Australian wanted me to print.” I ask for a copy and he generously hands one over. On it is about four paragraphs composed by Bag on his letterpress. It is an ode of sorts to Gutenberg’s invention, to the fading era of the letterpress, and to Bag’s skill:

“Punches: printing’s heart. Punches like those that we goldsmith-guildsmen use to impress into our work our sign, our maker’s marks. Finger length steel bars, but instead of a maker’s mark carved in raised relief upon the end, Guttenberg wished a letter, a punch for each letter of the alphabet, raised in relief and in reverse ...

The metal will set and then be removed. The cast letter, the piece of type, will be raised and appear reserved, mirror image of the punch. The punch will be the master, the type the copy. We will make hundreds of each letter, and then assemble them into words and sentences, fix them firmly into a form, ink their raised surface, and by pressing paper to them transfer to the paper the words and sentences we will have assembled piece by piece, letter by letter, from type cast from matrices made from punches. The printed text will appear correctly, no longer reversed. A printed page. Printing with movable type. Guttenberg’s dream. An invention still to be realised ...”

Anuradha Sengupta is a writer based in Mumbai