Attari, India: Real estate prices have jumped sharply in recent months in this area where India meets Pakistan, as resorts and roadside restaurants sprout up, eating into the lush wheat fields of northern Punjab state.

Driving the increase is a bet that relations between the longtime adversaries will continue to improve as memories of the 2008 Mumbai attacks, blamed on Pakistani insurgents, fade and long-suppressed trade between the nuclear-armed neighbours grows.

In the wake of a July 2011 agreement to resume peace talks, the two sides last month pledged to ease visa requirements for businesspeople, pilgrims, tourist groups and senior citizens. Pakistan has said it will also allow companies to trade about 6,000 products with India — up from 137 — matching India’s rules.

India unilaterally announced in August that it would allow Pakistani firms to invest in any industry but defence, space and nuclear energy.

Politicians in both countries herald the prospect of closer ties as “a new era”, a “win-win” and a way to alleviate regional poverty and unemployment. The hope is that greater trust will eventually help solve more intractable disputes over water usage, the divided Kashmir region, a deadly military standoff on the Siachen Glacier and Pakistan’s alleged support of terrorism.

“If there has to be a war, let it be a war of economic competence and excellence,” Muhammad Shahbaz Sharif, chief minister of Pakistan’s Punjab province, said recently.

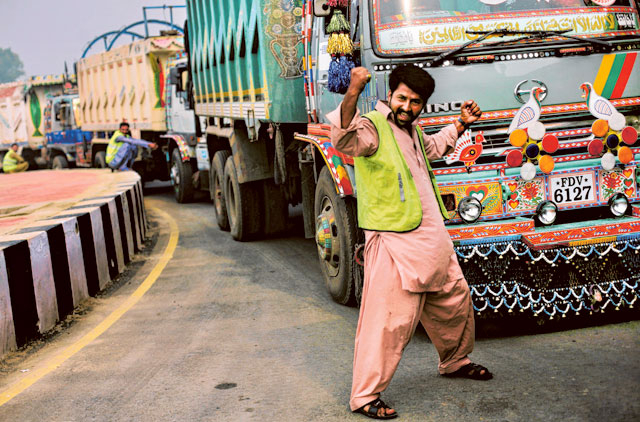

So far, the new Indian businesses lining the 18-mile road between the Attari border crossing and nearby Amritsar aren’t exactly rolling in rupees. On the Pakistani side, a line of parked trucks more than a mile long snaked toward India’s new 118-acre cargo and passenger gateway, the drivers playing cards and making minor repairs to their vehicles as they whiled away the many hours it takes to get through the crossing.

Painfully slow

The well-organised Attari Integrated Check Post, the first of 13 planned along India’s 9,300-mile land border, belies India’s reputation for poor infrastructure. More than 10 times larger than its predecessor, the terminal boasts metal detectors, currency exchange counters, a prayer room, banks, cafeterias and about 230 security cameras.

But ratcheting open the gates between the nations hasn’t been seamless. The visa deal was reportedly delayed four months while the two sides quibbled over where the signing would occur. (It finally took place in Islamabad) And implementation has been painfully slow.

With fewer than 200 people, on average, crossing the border each day, the terminal’s flat-screen computers mostly sit idle as bored immigration officials read newspapers behind their shiny desks. India’s terminal opened in April, 10 months behind schedule, but more quickly than Pakistan’s renovated Land Freight Unit, which remains unfinished.

“We’ve no idea when it will be done,” said Amanjeet Singh, the Integrated Check Post’s assistant commissioner of customs, as he signed documents and slid them to the floor for an aide to recover, a practice seen among some senior bureaucrats. “They are tight-lipped about the entire situation.”

Under the nose of wary border guards, each country handles imports on its side of the divide as they are delivered by the other nation’s trucks. Once unloaded, usually within a few hours, the trucks immediately turn around, ensuring that they never remain overnight.

So far, Pakistan is importing mostly vegetables, livestock and newsprint, while India is importing dried fruit, cement and gypsum. If relations continue to improve — a big if for neighbours that have gone to war three times since 1947 — trade could double within three years, experts say, up from the current $2.7 billion annually and about $300 million in 2004. Traders are hopeful.

“In the past, the two countries would move 10 steps forward and 100 steps back,” said Amjad Riaz, 58, an exporter and former president of the Karachi Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Pakistan, who says land prices are also rising on his side of the border as more terminals, restaurants and truck stops are built. “Now it’s like we’ve moved 20 steps ahead.”