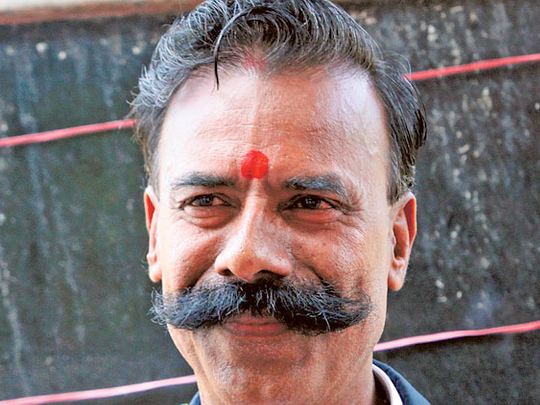

NEW DELHI; Indian shop owner K. Padmarajan doesn’t feel like a loser. In fact, he sees much to celebrate in the 158 times he has stood for public office and failed.

Starting out in 1988, he had a point to prove — to those who laughed at the ambitions of a man who repaired tyres for a living and to the cynics who scorned Indian democracy with all its flaws and inefficiencies.

“Back then, I owned a cycle puncture repair shop and a thought struck me that I, an ordinary man with an ordinary income and no special status in society, could contest the elections,” he told AFP.

He lost. And then lost again and again. Over 26 years, he has competed hopelessly for local assembly seats and parliament, often standing against big names such as prime ministers A.B. Vajpayee or Manmohan Singh.

In all, he says he has forfeited 1.2 million rupees (Dh73,000 or $20,000) in deposits tendered in his lonely pursuit, in the process earning a place in the Limca Book of Records, the national repository of India’s eccentric record-making.

“I have never contested an election to win and the results just don’t matter to me,” laughs the entrepreneur whose tyre shop has flourished alongside his other business, a homeopathic medical practice.

His best result came in 2011 when he stood for an assembly seat in his home constituency of Mettur in southern Tamil Nadu state. He won 6,273 votes, raising the prospect that one day he could be victorious.

“I’m just someone who is very keen on getting people to participate in the electoral process and cast their vote and this is just my means of generating awareness on the same,” he added.

Yesterday, he was standing in Vadodara, the constituency of election front-runner Narendra Modi in western Gujarat state, which goes to the polls in the latest stage of the country’s mammoth election.

Results on May 16 are expected to confirm the return to power of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) after ten years in opposition in the 543-member national parliament.

“I always chose to contest against the newsmakers. At the moment, if there’s one VIP who’s making all the headlines, it’s Narendra Modi,” Padmarajan explained by telephone.

Every five years India heads to the polls in what is always the world’s biggest election, awe-inspiring in scale and unrivalled as a display of political self-determination.

Surveys show the 814-million-strong electorate in 2014 is fed up with corruption, worried about jobs and angry about rising prices.

One carried out by the US-based Pew Research Centre between December and January showed 70 per cent of respondents dissatisfied with the direction of the country.

But even after a term of government marked by a dysfunctional parliament and corruption scandals, faith in Indian democratic institutions remains strong. Seventy-five per cent of respondents had “a lot” or “some” confidence in the lower house of parliament.

Election turnout so far has been high, with young voters leaving polling stations excitedly preparing their “fingie” for social media — a “selfie” showing one’s finger marked with ink.

“Indian democracy is alive and well and very healthy,” said Jagdeep Chhokar from the Association for Democratic Reforms, a non-profit group that analyses election candidates. “Every Indian without exception is proud of India being a democracy. Indians are very good and even smug that we are a democracy and China is not,” he explained..