Dubai: On the shores of the Creek in Bur Dubai end close to the temple and gurudwara and the Juma Mosque stands the 200-year-old Souq Baniyan, characterised by its mud walls and teakwood framed shops and traditional barjeel (wind) towers — a thriving testament to the centuries old emotional and business ties that Indian traders have had with this land.

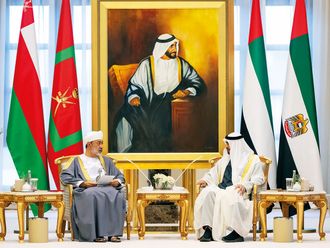

Many of these trading families came here generations ago before the formation of the UAE, braving the harsh weather without the comforts of air-conditioning or fans as electricity came here only in 1959. They did business by the light of Petromax and earned the respect of the rulers. Undying friendships and bonds of trust were forged that continue even today. As His Highness Shaikh Mohammad Bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, renews these old ties in India, the traditional traders of Souq Baniyan reminisce about the golden bygone era.

The one-kilometre-long open souq got its name Baniyan from the traditional Hindu traders who came from Thatta in undivided India in the 1850s.

Maghanmal Pancholia, now 92, who came from Thatta in 1942 at the age of 18 to join his older brother, Paramanand Jethanand, to join the money exchange business at the souq, explained: “The Thattai Bhatia community, who had a monopoly in wholesale textile trading, wore the white tunic, Indian dhoti [traditional men’s garment] and a black cap and were called baniya and that is how the souq came to be known as Souq Baniyan. I recall as a young man a very vibrant and lively buzz in the market which had traders from everywhere rushing to the abra station near the old custom house as goods arrived or had to be loaded. The workers would be rushing with hand carts, there would be performers attracting crowds and there was so much good faith and camaraderie. Our rulers were most magnanimous, always wanting to solve every problem we faced, wanting us to stay with them. There were no banks in the early ’40s and Emiratis kept huge sums with us, trusting us completely. We maintained meticulous records and never faulted on any payments.

“We did not make much profit, just about Rs5 per case of 40 metres of cotton cloth but it was not only about profit, it was the goodwill and helpful community living that endeared us to the Emiratis. I was paying Rs100 each annually for my shop and my little room above the shop. When I moved out in the 1990s I was paying Dh100,000!”

Young boys from the Bhatia families came here to join the family textile business and usually lived a life of bachelorhood working in the shops on the ground floor and staying in first floor dorms called ghurfas. Cotton cloth from Indian was sold at four annas per yard and the most expensive cloth was old at Rs1 per yard. Boski silk, which came from China and was considered expensive, was sold at six annas per yard [16 annas in a rupee so four annas was quarter of a rupee]! Later, when the souq was flooded with Japanese and Chinese silk cloth for kanduras, expensive silk for jalabiyas and black abaya material did brisk business and was traded from here right up to Basra in Iran.

At one time there were about 500 Bhatia families dealing in wholesale textile and about 200 Iranian traders from Bastaki. While textile was the mainstay, foodstuff and pearl trading was another area that some dealt in. As Dubai grew exponentially, traders moved to bigger, better malls, but at least five Bhatia families have held on to the businesses started by their great-grandfathers and continue to operate out of the same shops as did their forefathers.

The sons of Vallabdas Kehsavdas — Jaiprakash, 75, and Prakash, 67, — run their shops which are 90 years and 70 years old respectively. “Our father came here in 1925 and I came here at the age of 15 in 1959 while my brother came here in 1965. But in those days our life existed within the four walls of the souq. We shared such synergy with the Emiratis and we were all so happy. There was no electricity or running water and spending time on the sand dunes just outside this souq or going to the National Cinema in Al Nasr square by abra were some of our ways of recereation. But the trading was our lifeline and we absolutely enjoyed the robust competition as business was brisk,” said Jaiprakash who, along with his son Hiren, continues to operate out of the same shop as they feel the place has a strong sentimental value.

Hiren points to the traditional old door at the end of the souq. “There were two doors at each end which were shut at 5.30pm as it grew dark and the souq would shut down. No traders ever locked the doors of the shop and there would be a policeman always on duty at the souq, but there was no fear of any theft. The by-lanes of the souq were only 5 feet broad, barely enough for two people to walk side by side. Later, in the 1960s, shops were pushed back to widen this during renovation.”

Prakash speaks of the easy access Indian traders had to the majlis of Shaikh Rashid Bin Saaed Al Maktoum. “We were welcome any time and could walk into the majlis without an appointment with our grievances. Shaikh Rashid was a generous and large-hearted person who would always resolve every issue we faced.”

Hemu and Harendra Bhatia, who came here in the late Sixties, continue to run the shop their father, Tolaram Jagumal Lilwa, started and their sons have joined them too. They feel indebted to the rulers. “Earlier, when we were young boys in Mumbai, we were so comfortable, we felt being sent to Dubai was a punishment. Parents would often admonish boys and say study hard or else we will send you to Dubai! Life was tough and our parents who came here in the 1940s learnt to live frugally. I used to often wonder why my father wanted me to stay here when I was sent here in the early 1970s. However, after a few years I understood the value. While we were born in India, this place nurtured us, provided us earnings and today even if the rulers ask us to leave, I would salute them with respect for what they have provided us,” Hemu Bhatia said.