Washington: A year ago, President Barack Obama boldly, unequivocally demanded that Israel stop building colonies on the West Bank and occupied east Jerusalem. Today he's left with little choice but to swallow a stinging and very public rebuke from America's closest Mideast ally.

Why?

Too much is at stake. The administration has invested too much time, credibility and political capital to throw up its hands and walk away from its hard-fought efforts to get Israel and the Palestinians back to peace talks.

An open fight with Israel is the last thing Obama needs in the midst of domestic political turmoil that has snarled signature efforts like health care reform.

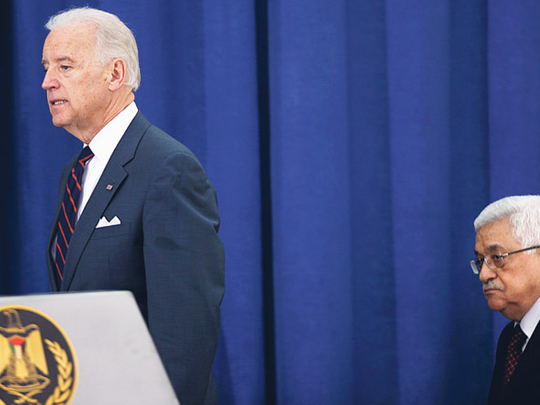

But the White House has signalled deep anger and probably won't forgive or forget Israel's boorish behaviour. Vice-President Joe Biden had gone to Israel and the Palestinian territories to reassure the Jewish state of unstinting American support and to praise Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas for agreeing to resume peace talks.

Biden's was the highest-level visit to Israel since Obama took office — a fence-mending journey after a very difficult year in US-Israeli relations.

The vice-president was virtually in mid-blandishment when the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pulled the rug from beneath him. It announced plans to build 1,600 new homes in an occupied East Jerusalem neighbourhood.

After then showing up very late for dinner with Netanyahu, Biden issued a statement condemning the new Israeli move and declaring that it undermined trust just as US-brokered talks were about to resume after a 14-month hiatus.

The Obama administration decided to use the word ‘condemn' — the strongest kind of diplomatic language — after a 90-minute debate among the Biden party in Israel, the National Security Council and the State Department.

A day later, State Department spokesman P.J. Crowley expressed bafflement at the Israeli action.

"It would be unusual for an Israeli government to take this kind of action while the vice-president is standing next to the prime minister. We are talking to the government and trying to understand what happened and why," he said.

Given Israel's powerful rebuke during a visit by the vice-president, the question arises: Why did Obama choose the policy he did from the outset of his term in office?

Through a year of ragged relations, the Obama administration had moved from stark demands that Israeli end all colony building in the West Bank and occupied East Jerusalem, to praise for the Netanyahu government for agreeing to a temporary suspension of colonisation activity — except in occupied East Jerusalem.

In moving from one point to the next, Obama became just the latest American president to crash against the impenetrable stone walls, the unbending positions that have time and again blocked Mideast peacemaking.

Goal

The goal Obama set out to reach was not only a formal, lasting peace after decades of war and antagonism, but the creation of a Palestinian state in the West Bank. To get there, Israel and the Palestinians had to overcome deep disputes over who controlled what territory.

By initially demanding Israel change tactics on colonies, there was the assumption that Obama had also told Netanyahu that there was an "or else".

That "or else" — some form of withholding aid or arms or just a diplomatic cold shoulder — would, however, have ensured a political explosion among Israel's supporters in the US, particularly among the powerful Jewish lobby.

Perhaps Obama, in taking his tough initial tack, had not foreseen the deep political divisions he would face a little more than a year into his presidency.

"He can't win on [Occupied] Jerusalem right now. No matter how humiliating, he has to swallow it," said Aaron David Miller of the Woodrow Wilson International Centre for Scholars.

Working with Israel, said Miller, "is like dancing with a bear. Once you start, you can't let go."