London: Palestinian negotiators privately accepted Israel's demand that it define itself as a Jewish state, the leaked papers reveal, while Israeli leaders pressed for the highly controversial transfer of some of their own Arab citizens (Palestinians in 1948 areas) into a future Palestinian state as part of a land-swap deal.

Both issues go to the heart of the two-state solution to the conflict which 20 years of negotiations have failed to deliver.

Palestinian Authority leaders publicly reject any ethnic or religious definition of Israel, and it is fiercely opposed by many of Israel's own Palestinian citizens.

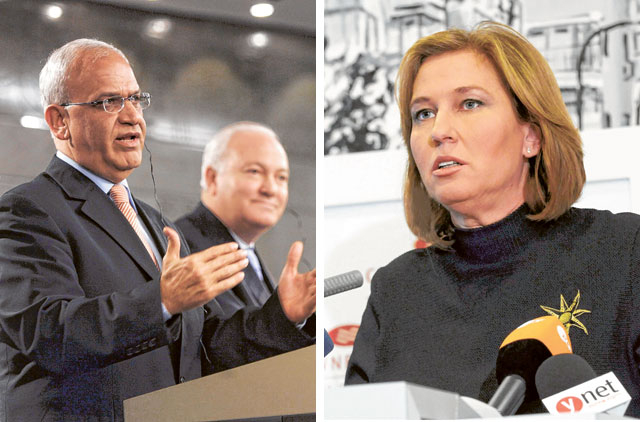

When Israel's Likud prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, said last Oct-ober he would temporarily halt colony building in exchange for Jewish state recognition, the chief Palestinian negotiator, Saeb Erekat, described it as a "racist" demand.

But behind closed doors in November 2007, Erekat told Tzipi Livni, the then Israeli foreign minister and now opposition leader: "If you want to call your state the Jewish state of Israel you can call it what you want," comparing it to Iran and Saudi Arabia's definition of themselves as Islamic or Arab.

Insistence by Israel and the US that Palestinians recognise Israel as an explicitly Jewish state, as part of a final settlement of the conflict and as being potentially linked to a loyalty oath for Palestinians in 1948 areas, is the focus of growing controversy.

Palestinians see it as effectively closing down the "right of return" of refugees to what is now Israel, and undermining the national and civil rights of the country's 1.3 million-strong Arab minority.

Legitimising Zionism

The PLO and Israel formally recognised each other in 1993. But accepting Israel as an ethnically or religiously defined state is highly neuralgic, not least because it would be regarded by Palestinians as endorsing the legitimacy of Zionism.

Erekat signalled acquiescence but refused to formally discuss the matter further. "I don't care," he insisted in June 2009. "This is a non-issue. I dare the Israelis to write to the UN and change their name to the ‘Great Eternal Historic State of Israel'. This is their issue, not mine."

But throughout the 2007-08 negotiations, the papers show, Livni and other Israeli negotiators emphasised that the Jewish character of Israel meant all Palestinians should look to a future Palestinian state to fulfil their national aspirations.

In several areas, Livni pressed for Palestinian citizens in 1948 areas to be moved into a Palestinian state in a land-swap deal, raising the spectre of "transfer" — in other words, moving Palestinians from one state to another without consent. The issue is controversial in Israel and backed in its wholesale form by rightwing nationalists such as the Yisrael Beiteinu party of the foreign minister, Avigdor Lieberman.

During talks in April 2008 about the future borders between Israel and a Palestinian state, and land swaps to allow West Bank Jewish colonies to become part of Israel, Livni raised the issue of "some Palestinian villages that are located on both sides of the 1967 line about which we need to have an answer, such as Beit Safafa, Barta'a, Baqa Al Sharqiya and Baqa Al Gharbiya".

Earlier, she is recorded as having made clear that such swaps also meant "the swap of the inhabitants".

Two months later Livni again argued for the transfer of Palestinians in 1948 areas from villages to a Palestinian state.

But Ahmad Qorei (Abu Ala) replied: "Absolutely not." And when Livni's fellow negotiator, Udi Dekel, mentioned another village on the Israeli transfer list, Betil, the Palestinian leader, explained at once: "This will be difficult. All Arabs in Israel [Palestinians in 1948 areas] will be against us." To which another member of Livni's team retorted: "We will need to address it somehow. Divided. All Palestinian. All Israeli."

Message

The message that Livni and her fellow negotiators wanted to get across was clear. In January 2008 she told Palestinian leaders: "The basis for the creation of the state of Israel is that it was created for the Jewish people. Your state will be the answer to all Palestinians, including refugees. Putting an end to claims means fulfilling national rights for all."

Qorei had already stated flatly: "We'll never accept any change in the reality of the life of the Arabs living in Israel or their transfer. They're Israeli citizens." But Livni's implication was that the Palestinian state should be the answer for the Palestinian citizens of Israel, as well as millions of refugees and their families who fled or were forced out in 1948.

‘I am against law'

Both proposals appear to contravene international law and UN resolutions on the refugees. But in an extraordinary comment in November 2007, Livni who briefly had a British arrest warrant issued against her in 2009 over alleged war crimes in Gaza is recorded as saying: "I was the minister of justice. I am a lawyer ... But I am against law international law in particular. Law in general."

She made clear that what might have seemed to be a joke was meant more seriously by using the point to argue against international law as one of the terms of reference for the talks and insisting that "Palestinians don't really need international law". The Palestinian negotiators protested about the claim.