Cairo: Founded in 1928 as a pan-Islamic social and political group in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood has survived decades of suppression and emerged as the Muslim world’s most influential organisation.

Hassan Al Banna, a schoolteacher, set up the group in the Suez Canal city of Ismailia where he sought to propagate his Islamist ideology by engaging in social and religious enterprises.

In a matter of years, the Brotherhood generated a wide following inside Egypt and beyond. During the Second World War, Brotherhood branches were set up in other Arab countries such as Syria. The group is now believed to have affiliates in more than 70 Arab and foreign countries, apparently boosted by the Brotherhood’s rise to power in Egypt.

The group made its debut in Egyptian politics in 1944 when Al Banna launched a bid to run for parliament.

Apparently under pressure from secularist politicians who were worried about the Brotherhood’s growing clout, the then government reportedly reached a deal with Al Banna to drop his bid in return for banning prostitution and adopting Arabic as the official language at governmental departments. At the time, Egypt was under British occupation.

In 1948, the government of Mahmoud Fahmy Al Noqrashi outlawed the Brotherhood, accusing it of undermining state security. The ban was followed by a crackdown on the group’s members. Shortly after, Al Noqrashi was assassinated. Al Banna himself was gunned down in Cairo in February 1949.

Wary of secular leanings

In 1952, the Brotherhood backed a coup by the army against the monarchy. However, the Islamist group was wary of the secular leanings of the new rulers.

The Brotherhood’s relations with the junta hit their worst crisis two years later when the then-president Jamal Abdul Nasser survived an attempt on his life believed to be orchestrated by the group. Thousands of Brotherhood members were detained and the group was officially banned.

The Brotherhood was the target of another crackdown in 1965 when a number of its activists, including the prominent ideologue Sayyed Qutb, were executed on charges of seeking to overthrow the government.

The clampdown forced many of its followers to flee Egypt. Qutb was known for calling for armed struggle against secular governments in the Arab world.

When Anwar Sadat took over after Nasser’s death in 1970, the Brotherhood had a reprieve. The new president reached out to Islamists to undermine his leftist and Nasserite opponents. The rapprochement proved short-lived, though.

Sadat infuriated Islamists when he visited Israel in 1977, a trip that cleared the way for a peace treaty between both countries two years later.

In 1980, Sadat was killed by Islamist fighters at a military parade in Cairo. Al Jihad group, affiliated with the Brotherhood, claimed responsibility and its members were arrested and tried. A few were executed.

Upon taking office, Hosni Mubarak released hundreds of opponents, including Islamists, detained by his predecessor. Yet, the Brotherhood became the target of frequent swoops by Mubarak’s police during his nearly 30 years in power. Detainees were often tried at military tribunals whose verdicts could not be appealed.

Militants broke away from the Brotherhood and created their own groups blamed for deadly terrorist attacks, both domestically and internationally in the 1990s.

In Syria, the secularist regime of President Hafez Al Assad unleashed in 1982 a deadly crackdown to quell an uprising by the Brotherhood in the city of Hama. He also survived an attempt on his life, believed to be planned by the group.

An estimated 10,000 to 20,000 were killed in the “Hama massacre”.

Though officially banned in Egypt, the Brotherhood was allowed to field candidates as independents in parliamentary and municipal elections. In 2005 polls, the Brotherhood gained 88 seats or around 20 per cent of parliament.

Their leaders claim the group has denounced all violent tactics associated with the Brotherhood but analysts and intelligence services around the region remain sceptical.

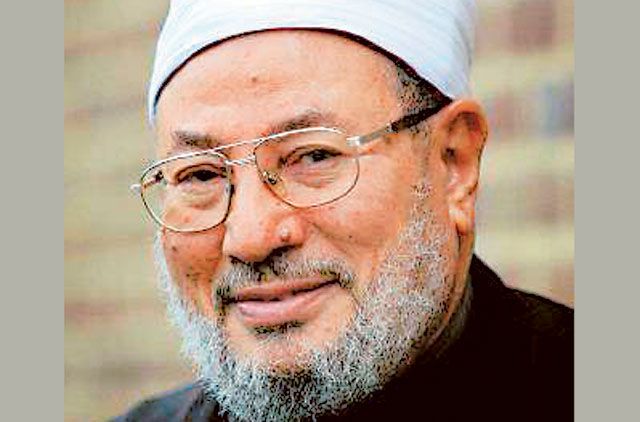

The Brotherhood continued to widen its popularity in Egypt and beyond due to an efficient network of social services and coherence. In an interview with the Egyptian independent newspaper Al Masry Al Youm in 2008, Yousuf Nada, a senior Brotherhood official who was living in exile at the time, said the group’s members worldwide were beyond the 100 million mark. The figure could not be independently verified.

Little is also known about the group’s finances. Senior Brotherhood officials say they are based on contributions offered by the members themselves. The Brotherhood has emerged as the big beneficiary from ousting Mubarak in a 2011 revolt.

In June 2011, the group’s first ever political party, the Freedom and Justice Party, was licensed. Being the country’s most well-organised group, the Brotherhood secured nearly half the parliament seats in the first post-Mubarak elections.

The gains accentuated splits and political inexperience of the young revolutionaries who played a major role in the uprising against Mubarak. Reversing an earlier decision not to field a contender for presidency, the Brotherhood nominated its senior member Mohammad Mursi, who became Egypt’s first democratically elected president last June.

Political gains

Islamists also made varying political gains in Tunisia, Jordan and Morocco. Still, Islamists’ rise to power triggered worries among liberals about freedoms and minorities’ rights.

In Egypt, Mursi’s first months in office were marred by sharp disputes with the secular-leaning opposition and the judiciary. The Islamist leader enraged both sides in November when he issued a decree granting himself sweeping new powers.

The crisis deepened when an Islamist-led general assembly rushed through a disputed draft constitution, which was approved by a narrow margin in a public vote in December.

The opposition accuses Mursi of acting at the Brotherhood’s command. Anti-Brotherhood protests occasionally degenerated into deadly clashes between the group’s backers and opponents. Several Brotherhood offices were attacked.

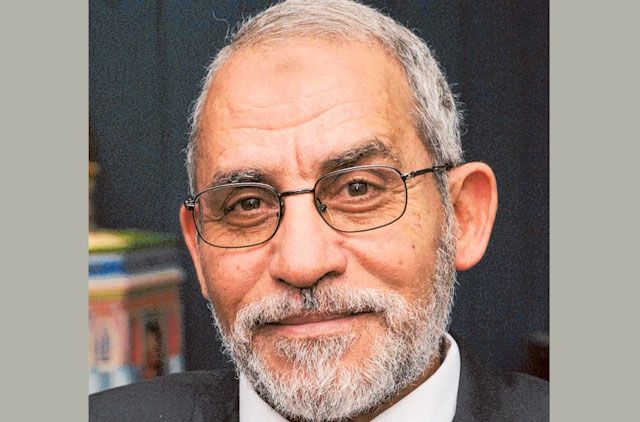

The Brotherhood claims that the opposition has joined forces with Mubarak loyalists to overthrow Mursi. “The Brotherhood has endured all kinds of oppression throughout the years,” said Mohammad Badae, the group’s supreme guide, in a recent message to followers. He described the Brotherhood as the “genuine revolutionaries”.

“The Brotherhood should abandon all its dreams of hegemony, which exceed its actual capabilities,” Hassan Nafae, a political expert told Gulf News. “Both sides have to look for a formula to save the sinking ship of the country...”