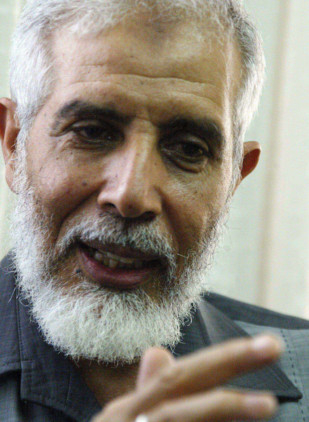

Cairo: During a recent night of opposition protests, people chanted against Egyptian President Mohammad Mursi and decried the draft constitution he was pressing. But the angriest and most fervent chants of all were aimed at a 69-year-old Islamist veterinarian, who many are convinced is secretly ruling Egypt. “Down, down with the Guide!” they yelled. The reference was to Mohammad Badie, the so-called Supreme Guide of the Muslim Brotherhood, the spiritual leader of the powerful if insular Islamist organisation that is the dominant political force in post-revolutionary Egypt. In the nearly two years since the popular uprising that ousted longtime autocrat Hosni Mubarak, Egyptians have rallied against what they have seen as a succession of threats to their revolution. But with the Brotherhood consolidating its power for the long term — electing one of its own as Egypt’s president and approving a new constitution that opens the door to an Islamist state — Badie may be the most lasting symbol of the polarised nation Egypt has become.

To the Brotherhood, the man known as “Al Morshed,” Arabic for “the Guide,” is simply the modest and devout spiritual leader of millions of members who feel free at last to express their conservative religious identity and exert political power.

The Brotherhood, whose credo is “Islam is the solution,” was banned for decades for being an alleged threat to the state. “Badie is a very quiet man who can repeat the verses of the Quran by heart,” said Essam Al Erian, a Mursi adviser and Brotherhood party official who scoffed at the idea that Badie somehow directs Mursi’s decisions.

“If you saw him in the streets, you could not distinguish him.” To many seculars, Christians and moderate Muslims, however, Badie is the dark prince of a coming Islamist tyranny, symbol of their worst fears and most far-flung conspiracy theories about how the Brotherhood operates.

During street protests, it is common to see images of Badie, who usually wears a suit and wire-rim glasses, depicted as an Iranian ayatollah or as Satan. A popular YouTube video casts him as Marlon Brando’s don in “The Godfather.”

“The Guide is the true ruler of Egypt,” said Radwa Badawi, 59, among the protesters one recent night who described what they believe are Badie-led plots to bring militias from Gaza or establish an Islamist caliphate across the Middle East and North Africa. “Mursi, the president, has nothing to do with any of it. He just executes the orders of the Guide. “

The reality of Badie’s influence is more complicated and difficult to know. According to analysts, he is a relatively uncharismatic figure who was chosen for the top position in 2010 partly for that reason: Over the years, he distinguished himself by being indistinguishable from more powerful members of the Brotherhood. “He is easy to control, and ideologically and intellectually, he is in harmony with the Guidance group,” said Ashraf Al Sherif, a political science professor at the American University in Cairo, referring to the powerful 19-member body that sets policy and has supplied key officials in Mursi’s cabinet. “Badie is in the position first and foremost because they trusted that he is ‘one of us.’”

Born in the southern governorate of Beni Suef, Badie married the daughter of a first-generation Brotherhood member. He is a “patient man” who quotes Quranic verses “even when he talks about soccer,” according to the Brotherhood’s official website.

Badie rose through the ranks working in roles focused on education while eschewing more outwardly focused political work. In 1965, Badie was arrested along with thousands of others in connection with the trial of Brotherhood leader Sayyid Qutb, an influential intellectual who laid the groundwork for many modern Islamists. Qutb was hanged for allegedly plotting against the state.

Badie and several others were released in 1974 and went on to become the modern power center of the movement. “We were tortured by dogs, by whips, by tools,” said Diaa Al Tobky, a retired airline pilot and Brotherhood member who met Badie in prison and said he was almost certainly tortured as well. “They would pull out our beards with pliers.” Al Tobky recalled Badie as a “faithful” young man who went from cell to cell attending to prisoners’ ailments. He said prison only strengthened their religious commitment.

“We like to say that the Muslim Brothers are like nails,” said Al Tobky. “When you hammer this nail, it only goes deeper into the wood.”

After Badie was released, he worked as a Brotherhood official in Beni Suef until he was elected to the Brotherhood’s Guidance Bureau in 1993. “He was somebody who had very little public exposure outside of the movement,” said Nathan Brown, a professor of international affairs at George Washington University.

“There were people in the Brotherhood who were basically uncomfortable with taking a prominent political role and wanted the movement to withdraw into itself and focus on unity. They felt the time wasn’t right for organised politics. Badie was in this camp.”

When Mustafa Kamal Al Sayed, a political science professor at American University in Cairo, met Badie at a gathering recently, Badie “hugged me several times and was quite cheerful,” he said. Then the two of them got into a discussion about whether women and Christians could be head of state in Egypt.

“He was not against women and Christians having civil rights, but for him, the head of state must be a male Muslim,” Al Sayed said, adding that Badie’s arguments struck him as more dutiful than scholarly.

As the Brotherhood has turned toward politics, Badie has been overshadowed by more powerful figures in the Brotherhood’s Guidance Bureau, experts say. These include Khairat Al Shater, a wealthy businessman considered the financier and strategic thinker of the organisation, and Mahmoud Ezzat, considered the enforcer of internal discipline. In his role as Supreme Guide, Badie delivers sermons and speeches that reflect a consensus within the Brotherhood rather than his independent thoughts or directives.

“You hear Badie saying that the protests against the president are a conspiracy led by people from the Mubarak regime,” Al Sayed said. “And then this is exactly what you hear the president saying.”

The harmony between Badie and Mursi and the new, Islamist-backed constitution has brought a sense of profound relief to Brotherhood members such as Al Tobky, who was imprisoned with Badie. Relaxing in his sunny apartment in suburban Cairo, he said the key to understanding the Brotherhood’s success is trust.

He trusted that Badie was being faithful to Islam, and he trusted that Mursi was being faithful to Badie. Egypt, he said, is finally moving in the right direction. “In this country, we’ve had Muslims but no Islam,” Al Tobky said. “But this is what we are trying to change, and it will change very soon, God willing, very soon I hope.”