Islamists' chance to lead change

Temper religious fervour with pragmatism to get mass support, scholar says

Cairo: Wrapped in a shawl on a cold morning, Jamal Banna shuffled over a dusty carpet amid fraying books on old civilisations. He knows well the intricacies of Arab history, but is far less certain where the upheavals of the last year will lead.

Like the balustrade winding to his library door, the known ways are crumbling. Moments of wonder are giving way to months of bewilderment. These days, he said, are likely to prove as seminal as those after the First World War, when western powers drew the borders that shaped the Middle East for nearly a century.

Islamists, who have endured decades of oppression, appear to have their chance to redefine the region's politics. "One era has ended," said Banna, one of Islam's leading liberal thinkers. "But of the new era, we don't know exactly what is taking shape."

Lacking an ideology and charismatic leaders to channel the aspirations of the street, the Arab Spring has been thwarted by more powerful forces and fallen short of complete revolution. The challenge for Islamists, Banna said, is tempering their religious fervour with a pragmatism that can fix their countries before anger and despair is turned against them. Banna is intimate with the Islamists' strengths and failings.

His older brother, Hassan, who was a schoolteacher, founded the Muslim Brotherhood in 1928. The younger Banna has often angered the group with his progressive interpretation of Islam. He has watched his brother's conservative vision evolve in the decades since his death in 1949. Grassroots activism gave way to periods of radicalism and today's often ill-defined mix of politics and social consciousness.

Passions

Only in Tunisia, he said, where a fruit seller set himself on fire a year ago and uncapped the passions of an entire region, is there a glimmer of a nation achieving its revolutionary ideals. Here in Egypt, the army rules. It has killed protesters and stifled civil liberties even as the nation votes for a new parliament. Security forces loyal to Syrian President Bashar Al Assad gun down protesters daily. Yemen is beset by warring tribes,

Muammar Gaddafi met a brutal, surreal demise, but Libya is torn by clan animosities and militias. Banna looked into the streaked morning light in his window. "The revolution," he said, "has lost its freedom." The rebellions against autocrats started with popular uprisings.

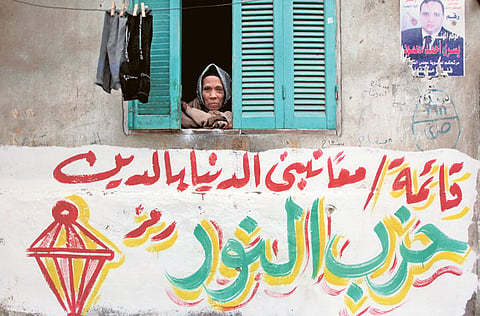

But in Egypt and other countries, they never found a consistent political voice. Young activists and Facebook rebels were not enduring or enticing enough to seize the moment. They still take to city squares, but the race for power has moved beyond them. "The heir of these revolutions is political Islam," said Banna.

"The Islamists' parties are the big winners. The Islamists are established figures in this time of tumult. They have credibility and people are willing to give them a chance. But they must move quickly to fix years of social and economic neglect. If not, they could lose this opportunity and it all might collapse."

The struggle between moderate and ultraconservative Islam over religion's role in public life will play out for years. There are already debates over banning alcohol and bikinis at Egyptian resorts.

Balance

The new political Islam must balance between pluralism and polemics, or else, as Banna suggested was possible in Egypt, "parliaments will become schools of bullies." The Islamic Al Nahda party in Tunisia "is more flexible than the Brotherhood in Egypt," he said. "Political Islam in Egypt hasn't reached that same kind of renaissance. It's happening at a very slow pace, and it needs time to bridge internal divides. But Islam will remain the pillar of public and private life. That is the destiny of the Middle East."

One of the most striking aspects of the Arab Spring is that the legacies of defeated autocrats will not be easily scoured away.

Hosni Mubarak was overthrown in a brisk 18 days; reinventing the country will take years. There are remnants of the old regime that don't want renewal, and the recent violence by security forces illustrates an increasing intolerance for dissent.

"It proves there are still many in the army and police who don't want the nation to succeed," Banna said.

An old academic ponders a new dawn

The 91-year-old scholar, Jamal Banna, moves gingerly, but his wit and intellectual rigour seldom rest. He has written scores of books and appears on talk show. His face is barely wrinkled. He runs a website and carries the title "president of the Revival Islamist Movement". His desk is stacked high with documents, and sometimes he appears not to be there, until one hears the rustle of papers, the creak of a chair.

Unfold a map and follow the coastal road from Tunisia through Libya and into Egypt. Names from books ring out: Carthage, Tobruk, Alexandria, all existing amid ruins, the won and lost possessions of history's changing empires.

The coasts, deserts and deltas are being remade again. But there was that moment in the chill of last winter when flags heralding something new coloured the streets and snapped in the wind. The fear had been broken. "What struck me most over the last year was the gathering of the masses," said Banna. "It was as if we had become a city of angels."

— Los Angeles Times

Sign up for the Daily Briefing

Get the latest news and updates straight to your inbox