Dubai: Embattled Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak has come long way in a country scornful of hereditary succession.

Mubarak came to power amid crisis three decades ago, a reassuring symbol of stability for many Egyptians as well as for Western leaders seeking a solid ally in the Middle East.

He was born on May 4, 1928, in the village of Kafr Al Moseilha in the Nile delta province of Menoufia. His family, like Anwar Sadat's and Jamal Abdul Nasser's, was lower middle class. After joining the air force in 1950, Mubarak moved up the ranks as a bomber pilot and instructor and then in leadership positions. He earned nationwide fame as commander of the air force during the 1973 Middle East war.

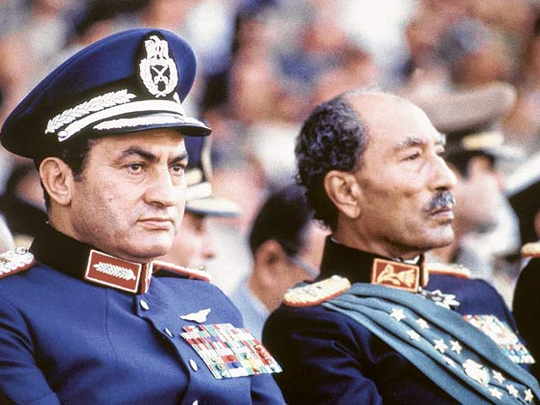

Mubarak, in military uniform and sitting on Sadat's right, escaped with only a minor hand injury on October 6, 1981, when a group of Islamist extremists gunned down Sadat and seven others in Cairo during a military parade,

Seven days later, Mubarak was president.Mubarak was serving as Sadat's vice-president.

Egypt's parliament designated Mubarak the sole presidential candidate the next day and he was elected head of state on October 13, 1981, with 98.5 per cent of the vote.

Early on, Mubarak strongly put down the militant insurgency whose strength had been underestimated, and whose ranks had produced Sadat's assassins and some of the future leaders of Al Qaida.

Later in the 1990s, he fought back hard again against another resurgence of Muslim militants who attacked both foreign tourists and ordinary Egyptians.

Mubarak engineered Egypt's return to the Arab fold after nearly a decade out in the cold over its 1979 peace treaty with Israel, and carved himself a role as a major mediator in the Arab-Israeli peace process.

He also made moves that promised he would open up society and that won him considerable popularity at home, including freeing 1,500 politicians, journalists and clerics jailed during Sadat's last months in office. But hopes for broader reform dimmed as, over the years, Mubarak was re-elected in staged, one-man referendums in which he routinely won more than 90 per cent approval.

Mubarak had never appointed a vice-president as the constitution required, though he did so last week in an effort to appease protesters demanding his ouster.

In early 2005, the Egyptian president — under pressure both at home and by the George W. Bush administration — surprised his country by saying he would change the constitution to allow Egypt's first multi-candidate presidential elections. The vote was held that September and Mubarak defeated 10 other candidates amid charges of voter fraud and intimidation.

In follow-up parliamentary elections, however, the Muslim Brotherhood — the country's main opposition group — stunned the government with a strong showing. Perhaps because of that, Mubarak's regime began sharply pulling back: postponing planned local elections, jailing activist Ayman Nour and launching its harshest campaign of arrests in a decade against the Muslim Brotherhood. As years went by, Mubarak also became more aloof, carefully choreographing his public appearances, and his authoritarian governing style appeared increasingly out of sync with a world focused on economic and political openness.

Resentment towards his regime built especially in recent years, as new press freedom exposed brutal police tactics, and a spate of economic reforms trickled down to only a handful of Egyptians.

More seriously for the West, Mubarak oversaw the wane of Egypt's regional influence in recent years as Hamas and Hezbollah and their patron, Iran, gained momentum and followers.

Yet throughout, Mubarak remained a strong ally of the US, carving out a niche as a key negotiator on the Palestinian crisis, and bolstered by billions of dollars in US aid because of his country's ties to Israel.

— With inputs from agencies